‘Need to balance transparency with donor’s privacy’: CEC on electoral bonds

By Soni Mishra- {{topics.sectionTitle}}

- {{item.tagTitle}}

HOT AND HAPPENING

Lok Sabha election: Polling to be held in 7 phases, counting on June 4

The voting for the Lok Sabha election will begin from April 19

Web desk

March 16, 2024

Masaan to Manekshaw: Vicky Kaushal on his Bollywood journey and marriage to Katrina Kaif | Teaser

THE WEEK's cover story this time is on Vicky Kaushal, who has fast become one of the greatest actors of his generation.

-

Bellie the Elephant Whisperer, one year after the Oscars | Exclusive Interview | THE WEEK

V. Bellie, one half of the Oscar-winning The Elephant Whisperers, is the first woman cavady in Tamil Nadu. In a conversation with THE WEEK, she talks about her love for elephants and how she enjoys taking care of them.

-

'Once a temple, always a temple'; historian Vikram Sampath on his new book on Gyanvapi | THE WEEK

In an interview with THE WEEK, Vikram Sampath suggests that Hindus and Muslims should engage in dialogue outside the realm of courts and political influence to resolve contentious issues amicably.

-

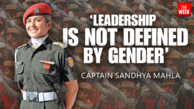

Meet the 26-year-old who led the first-ever all-woman tri-services contingent on Republic Day

In an interview with THE WEEK, 26-year-old Captain Sandhya Mahla talks about the lead-up to that historic feat, her journey in the Army and how gender does not define leadership.

International

- Russians cast ballots in an election preordained to extend President Vladimir Putin's rule

- Shelter-in-place order issued in Pennsylvania after shootings businesses closed parade cancelled

- Following are the top foreign stories at 2020 hours

- 'Expanding cooperation' with Afghanistan top priority of new Pak govt says Foreign Minister

- 2 Pak Army officers among 7 personnel killed in terror attack in restive Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province

Entertainment

- Excited to share screen space with Tabu Kareena Kapoor Khan on 'Crew'

- Anushree Reddy Ritika Mirchandani present their collections at Lakme Fashion Week

- Our mission is to bring joy in people's lives Designer Paras of Geisha Designs

- Sobhita Dhulipala on ‘Monkey Man’ Dream to be part of Dev Patel's vision

- Sara Ali Khan Shruti Haasan Fatima Sana Shaikh dazzle at day 4 of Lakme Fashion Week

Sports

- Indian shooter Ashi Chouksey finishes second in Polish Grand Prix

- IPL is not being shifted out of India says league chairman Arun Dhumal

- Hope he is not finished says Dravid on Ashwin as Shastri urges spinner to "harass more batters"

- Novak Djokovic withdraws from the Miami Open

- Six share lead with two rounds to go in Grand Prix Chess Series

Business

- Work on planting lavender along national highways starts in J K

- Timex Presents India Beach Fashion Week Where Timeless Style Meets Coastal Chic

- 100 Years 123 Feet Dosa MTR Celebrates 100 Years with a GUINNESS WORLD RECORDS™ Title for the Longest Dosa

- Dashmani Media Captivates 100 Million Across Varied Digital Entertainment Spheres

- Steel Titans Deliberate Infrastructure Evolution at Metalogic PMS Forum

The news was announced via social media by director Midhun Manuel Thomas

EDITOR'S PICK

'Murder Mubarak' review: Pankaj Tripathi shines as ACP Bhavani Singh in this whodunit

The plot is the king in this film based on the novel ‘Club You to Death’

-

Test Records: Bowlers with fifers in most countries

-

Transforming Dreams into Reality: Asense Interiors become leading player in Interior Design Bangalore Firms.

-

FitSpresso Reviews Scam (Must Read) Can FitSpresso Coffee Aid Healthy Weight Loss?

-

Quantum AI Rеviеw 2024: A Comprеhеnsivе Guidе

-

Best 10 Leaders in the metaverse industry