Manish Kumar sits on his father’s lap and observes the world around intently. Other than the tiny pair of spectacles that he is wearing, there is no other sign of the ordeal that the 14-month-old boy had to face. Kumar suffered from a congenital condition, which led to the deterioration of his left cornea soon after birth. In December last year, Kumar who lives in Chhapra, Bihar, was brought to LV Prasad Eye Institute in Hyderabad, where he underwent a corneal transplant surgery.

Kumar is lucky. The chances of him getting a corneal transplant in Bihar were nil, since the state has not collected a single cornea in the past one year. Even if he were to travel to other states, Kumar would have had to wait for weeks, if not months, for the surgery.

At LV Prasad Eye Institute, Kumar underwent the surgery within a day of the diagnosis. And, his treatment was done for free, given that his family could not afford it. The institute is one among the few institutes in India where there is no waiting list for receiving corneas.

When the cornea, which is the outermost transparent tissue of the eye, becomes cloudy because of infection, disease, accident or poor nutrition, it leads to blindness. In fact, it is the fourth most common reason for vision loss and blindness after glaucoma, cataract and age-related macular degeneration. According to National Programme for Control of Blindness (NPCB), India has 1.22 lakh bilaterally (in both eyes) corneal blind patients; around 25,000 to 30,000 new patients are added to the list every year.

Other estimates put the number of corneal blind patients at 6.7 million, out of which, 1 million are bilaterally blind. Of this, around 20 per cent could be treated through surgery or transplantation of healthy corneas taken from the dead. As of now, we need at least 6 lakh corneas each year for transplant.

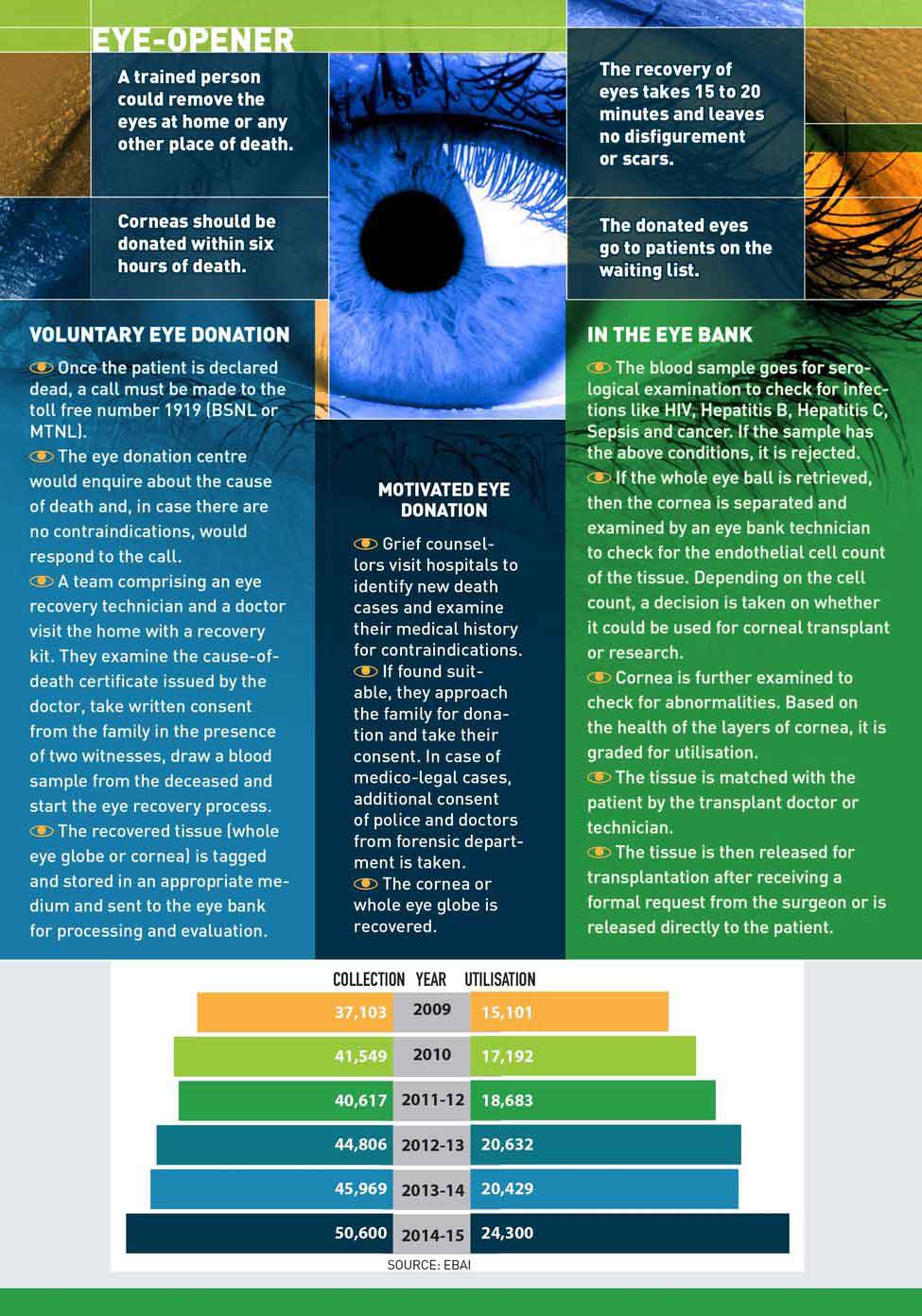

However, last year, only 50,600 corneas were collected across the country, of which 24,300 could be utilised, according to the Eye Bank Association of India (EBAI). In 2013, India accounted for 10.2 million of the world's deaths. Yet, the number of corneas collected in 2013-14 was just 45,969, of which only 20,429 were used. Corneas that cannot be used for transplantation or therapeutic purposes are used for teaching and research.

T. Kishan Reddy (in pic) is instrumental in getting over 2,000 families to donate the corneas of their loved ones in the past 21 years | Nagaraju Pala

T. Kishan Reddy (in pic) is instrumental in getting over 2,000 families to donate the corneas of their loved ones in the past 21 years | Nagaraju Pala

Apart from lack of awareness about cornea donation and shortage of skilled corneal surgeons, a major challenge is to run the eye banks more efficiently. Of 765 eye banks registered with EBAI, most are what are called eye donation centres, which are involved in the recovery of corneas, but do not undertake evaluation or processing of the organ. Many of them are not functional. According to EBAI figures, there are only 43 eye banks in India that collect more than 100 corneas a year, 36 eye banks that utilise more than 100 corneas and only four that utilise more than 1,000 a year.

Dr Samar Basak, president of EBAI, director of Disha Eye Hospital and medical director of cornea and eye bank services in Kolkata, paints a grim picture of the eye banks in India. “Truly speaking, 720 eye banks/eye donation centres are not up to the mark,” he says. “The EBAI is trying to work with the government for accreditation of eye banks for quality as per medical standards of eye banking in India. We are trying to incorporate Quality Control of India, too. But, time, manpower and monetary support are required.”

Dr N.K. Agarwal, deputy director general (O), directorate of health services, NPCB, says, they are in the process of setting up updated standards and norms for eye banks. “A committee was set up to review the guidelines of ‘Standards of Eye Banking in India 2009’ [a module created by NPCB] and we have reviewed and submitted our recommendations to the ministry,” he says. Also, the EBAI and a quality control committee are working together for accreditation of eye banks.

The model of eye banking is flawed in India. Since the 1960s, when eye banking started in India, little attention has been given to the number of eye banks and on whether they are functional and up to the mark.

Eye banking is a three-tier system: the eye collection centres collect the corneas. Next, an eye bank evaluates the organ, and, finally, the usable ones are preserved while the unusable ones are sent to training institutes.

Most eye banks are owned by non-profit organisations and trusts. Also, since the government used to give a grant to the eye donation centres based on each cornea collected, the focus has been on collection and not utilisation.

Manoj Gulati, country head of SightLife, a Seattle-based non-profit organisation that is working to eliminate corneal blindness, says, the US, which currently has a surplus collection of cornea, has about 50 eye banks across the country. “To have quality eye banks, we need to consolidate and reduce the existing number, if need be, and also convert the existing eye banks into collection centres,” he says.

If you look at the collection versus utilisation rate of the ten biggest eye banks in India, the utilisation varies from 82.4 per cent at Prova Eye Bank in Disha Eye Hospitals, Kolkata; 72 per cent at National Eye Bank in All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi; 23.5 per cent at Eye Bank Coordination and Research Centre, Mumbai and just 22.8 per cent at Pujyaniya Mata Kartar Kaur Ji International Eye Bank, Sirsa.

Stroke of luck: Manish Sharma of Bihar, who underwent a corneal transplant surgery, with his parents | Nagaraju Pala

Stroke of luck: Manish Sharma of Bihar, who underwent a corneal transplant surgery, with his parents | Nagaraju Pala

However, eye bank directors and cornea surgeons are of the opinion that judging an eye bank purely on its utilisation rate is wrong. Most eye banks in India depend on voluntary donations, that is, receiving calls from the families of the deceased who wish to donate the corneas. Most donors are above 70 and their corneas are not of transplant quality. Also, if the donor had certain contraindications like infection, septicaemia, blood cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, HIV, or Hepatitis B and C, the corneas are rejected. In addition, the banks receive a large number of corneas from eye donation centres that do the home visits and recovery.

“Many eye donation centres do not have trained technicians and the corneas get damaged in the process of recovery and cannot be used,” says Dr Sunita Chaurasia, consultant, cornea and anterior segment, and medical director of Ramayamma International Eye Bank (RIEB) at LV Prasad Eye Institute in Hyderabad. “There can also be delay in the cornea reaching the eye bank, which may affect its utility.”

One way to improve the collection and utilisation rate is through hospital cornea retrieval programme (HCRP). In this case, grief counsellors employed by eye banks or eye donation centres in hospitals motivate the family members of deceased patients to donate their corneas. This approach yields better results because the counsellors can pre-screen the donors, so there is better access to younger patients and the time taken to retrieve the cornea could be reduced. Thanks to the programme, the utilisation rate has touched 70 per cent across most centres as compared to 35 per cent in the case of voluntary donations.

Most counsellors working for the programme have trained under T. Kishan Reddy, currently operations manager of HCRP at Ramayamma International Eye Bank, which started the programme in 1990. Reddy is instrumental in getting over 2,000 families to donate the corneas of their loved ones in the past 21 years. “Families are distressed and aggressive when they lose their loved one. Over time, we have learnt when, how and whom to approach in the family,” says Reddy, who manages a team of 23 counsellors placed in hospitals in Hyderabad and four other centres in Telangana.

If a similar programme is implemented in all the government hospitals and even if corneas are collected from just 10 per cent of all hospital deaths, there would be enough to take care of all the patients. However, so far, only 50 eye banks have implemented the programme. “The legislative system should take a call and say that it will not recognise the eye banks which do not perform,” says Dr Pranav More, cornea transplant surgeon and eye bank manager at HV Desai Eye Hospital in Pune The hospital implemented the programme last November and, since then, its utilisation rate has jumped from 26 per cent to 50 per cent.

Ramayamma International Eye Bank, which is India’ largest eye bank with a collection of more than 4,500 corneas a year, has managed to create and follow protocols, and even train other eye banks. “Every donated cornea is important and every eye bank is supposed to follow the highest standards so that the corneas are preserved in the best possible manner and patients get good quality transplants,” says K. Hariharan, associate director of RIEB, which receives more corneas than it can use and sends the surplus across the country as requested by surgeons through EBAI and SightLife’s Cornea Distribution System.

A little planning and focussed efforts could go a long way in making an initiative work. The Rotary Aravind International Eye Bank at Madurai in Tamil Nadu is a case in point. Since November 2014, the eye bank, as part of its eye donation nodal centre project, has been sending two trained technicians and a coordinator to Kumbakonam, which is 200km from Madurai, to attend to eye donation calls day and night, with help from local volunteers. They collect the eye balls in moist chamber bottles, which are placed in styrofoam boxes along with ice packs and sent to Madurai via bus. At Madurai, a staff collects the boxes and takes it to the bank. In the past nine months, the bank has recovered 744 corneas with an utilisation rate of 56 per cent.

Graphics: Binesh Sreedharan

Graphics: Binesh Sreedharan

“Before we started the project, the eye donation centres depended on local medical practitioners for the recovery of corneas, but since they are busy with their practice, they cannot attend to all the calls,” says Dr M. Srinivasan, chairman emeritus of Aravind Eye Hospital, where the eye bank is located, and medical director of the bank. “Now our technicians screen the patients looking at their medical history, eliminating cases with contraindications and recovering corneas that can actually be utilised.” The bank plans to expand the project to two more centres.

Along with improving the facilities, it is important to create awareness about eye donation by dispelling misconceptions. The pledge card has no real legal holding and it depends on the family members to actually facilitate cornea donation. Assertive legislative action could go a long way in setting the agenda of eye donation in India. The US, for example, has pledge cards attached to the driving license.

In India, corneas earlier came in the same category as the other organs under the Transplantation of Human Organs Act and hence a request for organs was only mandatory for patients admitted in ICU. After much prodding by the EBAI, a directive was sent by the ministry of health and family welfare in 2011to all states to include a request for consent in the medical cause of death. However, it is yet to be implemented. Jaswant Mehta, chairman and managing trustee of Eye Bank Coordination and Research Centre in Mumbai, was following it up at the Centre and the state, however, there were lot of bureaucratic hurdles. Only after the Bombay High Court sought an answer from the directorate of health services in Maharashtra in June 2015 that orders to implement the required request column were communicated to all municipal corporations in the state. “We struggled for two years to get the column. We hope the others states, too, would follow the judicial orders,” says Mehta.

Currently India retrieves corneas from less than 0.5 per cent of all deaths. If we could increase it to 1 per cent, most of our needs would be met. We need more awareness, stronger legislative framework encouraging cornea donation and more eye banks or collection facilities.

Check point: A cornea being examined at Ramayamma International Eye Bank | Nagaraju Pala

Check point: A cornea being examined at Ramayamma International Eye Bank | Nagaraju Pala

FILL THE GAP

Maharashtra is one of the states with a better retrieval rate of corneas, however, the utilisation rate is still quite low. According to the directorate of health services, 8,286 corneas were collected in 2014, but only 2,600 transplant surgeries were conducted. There were 1,791 bilaterally corneal blind patients on the state's waiting list as on June 2015, but only 622 corneas were collected in that period, of which 259 were usable.

In Maharashtra, recipients have to directly register with eye banks and collect the corneas on their own when it is available. But there is no mechanism to ensure that the organ is handed over as per the waiting list.

In 2002, former journalist and activist Sampat Shetty filed right to information applications seeking more information on why the utilisation rate of corneas had come down. He got no response. So, in 2009, Shetty filed a PIL in the Bombay High Court. Based on the recommendations of an expert committee, the High Court has asked the directorate of health services to provide centralised data of recipients, with help from IIT-Bombay. “This will be a centralised list of recipients, but the distribution will be decentralised,” says Dr Prasanna Deshmukh, state nodal officer, National Programme for Control of Blindness. “It is a challenging task and will require six more months to develop.”

PAY IT FORWARD

Most people would consider it a thankless job, but Varsha Ved treats it like a mission. A senior counsellor with Eye Bank Coordination and Research Centre in Mumbai, Ved, 56, meets the relatives of deceased patients and talks to them about cornea donation. It means taking rounds of wards and visiting the mortuary at odd times of the day and night. The job is both physically and mentally demanding, but Ved, who is a BCom graduate, has been doing it for a decade with the same commitment and zeal. For she knows what it is like to live in darkness.

In 2000, Ved lost vision in both eyes after an infection in her cornea turned serious. A corneal transplant was the only solution if she wanted to see again. “My kids were still young and I felt I was totally handicapped,” says Ved, who registered with an eye bank, but had to wait for two years before she got her first corneal transplant. The second one was done a year later since doctors wait for the restoration of sight in one eye before conducting the second transplant.

“Those two years, when I couldn’t see, changed my perspective,” says Ved. “One can live without a limb, but losing vision is more drastic. I saw how much I was dependent on my loved ones for basic chores. It can derail someone’s life completely.” After regaining her vision, Ved decided to help others like her.

She starts her day at 10:30am with rounds of casualty, surgical wards, mortuary and emergency wards of the government-run King Edward Memorial Hospital. She speaks to the doctors and the families. The work is challenging, because relatives would not be in a frame of mind to donate organs. She also has to convince the doctor, who may be busy, to retrieve the organ and complete the formalities within the timeframe.

“We try to finish the entire procedure within 40 to 45 minutes after the family agrees to donate the cornea,” says Ved. “We make it a point to wait with the family and assist them till the body is released from the hospital.”

So far, Ved has managed to get eight to ten cornea donations a month and 150 to 200 a year. The utilisation is high in this case because the corneas are pre-screened. Next up, Ved plans to move to another government hospital and set up an active hospital cornea retrieval programme there. “I want to do this work till the end,” she says. Her son, a chartered account, and daughter, a lawyer, are supportive of her cause. “They tell me to do my work since it has the potential to save someone’ life,” says Ved.