Benode Behari Mukherjee, one of the greats of modern art in Bengal, lost his eyesight in 1957, when he was 53. But he never lost his vision. Undeterred by darkness, Mukherjee reinvented himself by relying on touch and memory to produce paper-cuts, sculptures and drawings. “Painting is a blind man’s profession,” Picasso said once, perhaps implying how colours and the visible light spectrum are subjective things. So when the Kolkata Centre for Creativity (KCC) released The Art of Benode Behari Mukherjee—the first in a series of Braille books on art—at the recently concluded India Art Fair, it seemed like a long overdue effort.

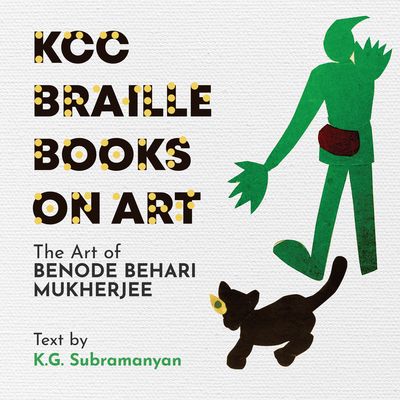

Published in collaboration with the NGO Access For All, the book serves as an introduction to the art and life of Mukherjee, enlivened through five paintings that have been converted into tactile artworks (with permission from Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation, named after his daughter), and an accompanying essay in Braille by K.G. Subramanyan, his student, friend and fellow modernist.

“Art books, most of which are exhibition catalogues, are more often than not written and consumed by the anglophone. As a result, we do not even have art books in regional languages to bridge the divide between the privileged anglophone and the rest, let alone enough books in Braille that discuss art and culture,” says Richa Agarwal, chairperson at KCC. “Realising this need, we have committed to creating at least one Braille book each year on an artist who can inspire people to engage with the arts, if not convince them to pursue it.”

Agarwal plans to honour another master from Bengal in the next Braille book to be published by KCC. The Art of Benode Behari Mukherjee has English text as well, printed in large font for the partiality blind.

It is indeed hard to produce an art book in Braille that truly appeals to, and benefits, a visually impaired adult. Verbo-visual prompts are never enough to fully convey the transformational power of a work of art. Arctic Circle: A Tactile Graphic Novel For Blind Readers (2016) has the artist Ilan Manouach construct an entirely new language as part of his “conceptual” comic book about a pair of climatologists in the North Pole. “To make comic books accessible to the blind, Manouach devised an entire new language composed of sculptural, touchable symbols and patterns, which are pieced together to tell a story….” writes a reviewer in the online arts magazine Hyperallergic. “The result is Shapereader, a system of tactile ideograms, or ‘tactigrams’—haptic equivalents for objects, actions, feelings, characters and other features of any story. They are raised shapes on wooden board, and have more in common with Chinese pictograms than with Braille letters or the Roman alphabet, in that they are textural depictions of what they represent.”

In India, we are yet to see innovative art books that are so thoughtfully produced for the blind or the partially impaired. “While a number of blind schools and Braille presses are active, making visual arts and artists accessible to the visually impaired has remained low priority,” says Agarwal. “KCC’s Braille Books on Art series attempts to bridge this gap by converting two-dimensional artworks into tactile artworks that could be felt and experienced physically.”

Siddhant Shah, founder of Access for All, has been at the forefront of improving the “experiential culture” of public spaces. From museums and lit-fests to art fairs and heritage institutions, Access for All has worked on altering access for people inhabiting a spectrum of development disabilities. From creating a physical Braille copy of The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay, winner of the 2019 JCB Prize for Literature, to making the first Braille handbook for the State Bank of Pakistan’s Museum and Art Gallery in Karachi to coming up with Braille copies on menstrual hygiene, banking and lifeskills, Access for All is perhaps the first point of call in India to produce tactile books that improve readership beyond textbooks for the visually impaired. Shah’s own vision of what constitutes a Braille book has evolved after receiving feedback in the last seven years when Access For All was first established.

“Once we had a very interesting observation from a colleague of a visually impaired person. She said that when this person is reading the book, we become visually impaired because we don’t know Braille. So for us, the information is not accessible,” says Shah, 31. “And that really startled us. We began thinking of ways to bring things together in such a way that everyone can use it. Rather than segregating people under the name of accessibility, we thought of having more of an integrated model.”

Access For All’s three-member team, with an in-house workshop, painstakingly works in an in-house workshop with a veritable library of texture and materials, and patterns and permutations of lines and dots overlaid on images to offer a more fulsome experience. His own inspiration is his mother, who has only partial eyesight. Shah’s next big project: roping in artists with disabilities in India and the UK for a one-of-a kind arts festival.