Adnan Sami made headlines when he got his Indian citizenship last Republic Day. It was an opportunity for chest-thumping for some in the Indian media because a person of Pakistani nationality had chosen to become Indian. Sami’s decision was pragmatic. Mumbai is a mecca for artistes, and the hassle of renewing work visas can be extremely frustrating; more so if you are a Pakistani. While Sami’s Indian nationality is interesting, he is not the only ‘Indian by choice’. Many become Indians through marriage. Sonia Gandhi is the most famous and influential videsi desi. There are others who are drawn by love for India, or something unique it offers. Many of them have enriched India with their contributions, whether it is fighting the caste system or drafting the rural employment guarantee scheme.

India demands a price from those who choose to be Indian. Dual citizenship is not allowed for Indians. You are either an Indian or you are not. There are no half measures, no split identities. The process of becoming a naturalised Indian is also tiresome. One has to live in India for at least 12 years to be naturalised. Of course, marriage to an Indian expedites matters, and Gail Omvedt did exactly that. “Foreigners” born in India between 1950 and 1987 are automatically conferred Indian citizenship, a clause Tom Alter used. If you have no such advantages, the wait can stretch to decades, and only those as persistent as Father Sopena succeed.

This, however, is not the space to mull over the deficiencies or loopholes in Indian citizenship clauses. Here, we celebrate those who became ‘Indians by choice’, through their stories. Read on.

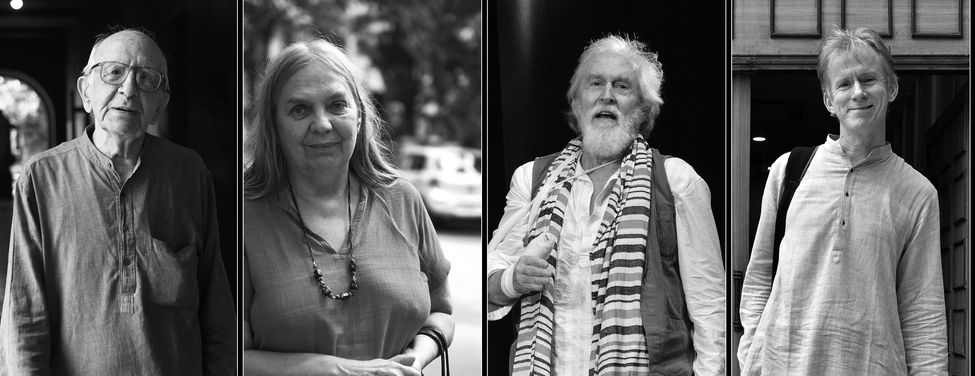

Federico Sopena Gusi | Salil Bera

Federico Sopena Gusi | Salil Bera

Federico Sopena Gusi, 90

Country of birth: Spain

Place of residence: Mumbai

Profession: priest

Father Sopena, Indian national,” he said with a warm handshake as he ushered us into the parlour of the Jesuit seminary Vinayalaya in Mumbai. The seminary has been Sopena’s home, off and on, for most of his long life. He has lived 67 of his 90 years in India, but has been an Indian citizen for less than a year.

Federico Sopena Gusi was sent to India in 1949 as a priest newly ordained into the Jesuit order. When he landed in Mumbai, his lips rounded in a “Wow”as a whoosh of humid tropical air hit him. He fell in love instantly. “I still remember that soon after landing in Bombay, I heard foreigners who had lived in India for five years could apply for citizenship, and I thought of how lucky they were,” he said. A few days later, India adopted its new Constitution and rules changed. It did not bother him much then: he was 23, still recovering from having left behind his family and here was a whole new world of opportunity and exploration awaiting him.

He immersed himself in work, learning Indian philosophy and theology, and working with the tribals in Maharashtra. The sight of a tall white priest sputtering on his scooter down the dusty roads leading to far-flung hamlets became a familiar one in tribal areas. His Indian family became bigger and bigger. “Then I read a couplet by Kabir which says that blessed is the man who has cleared all his debts and dies in his own country. As a priest, I have no debts, but I wanted to die in my country, and that was India.” He began writing letters to various authorities for citizenship, but the effort came to a halt when an officer from the ministry of home affairs accused him of converting people. “I said I was only interested in one conversion, mine, but my application was turned down.”

Sopena’s life and work continued, however. There are several orphans around Andheri in Mumbai who will tell of how he held their hand and guided them. Shaikh Amin, author, and owner of the cafe Bombay to Barcelona, is one such street-child, who speaks fondly of Sopena and visits him often.

For Sopena, being a foreigner meant the headache of getting his visa renewed every year. But more than this logistical hiccup, the feeling of not officially belonging to the country he had adopted bothered him. He tried repeatedly, and failed. It was finally the efforts of social worker Vinita Patil, with whom he has worked in tribal belts, that succeeded. Patil realised several of his submissions had “got lost”, and spent months trying to retrieve them. She finally gifted Sopena his most cherished prize, the certificate of naturalisation, this April. Before that, there was one more formality. He had to relinquish his Spanish nationality. It was not a pleasant experience, some officials were not sensitive. But he told them, “I am proud to be Spanish, but I’ve lived all my life in India, I have to be an Indian.” He then went to the district collector’s office and took the oath of allegiance and got his citizenship.

“Now I have to get my Aadhaar card and passport. All that can wait. I’m in no hurry to go anywhere. Of course, as a Jesuit I can be sent anywhere. But now, even if I go to Alaska, it will be Father Sopena from India. It’s a big difference.’’

As an Indian now, Sopena is sad at the polarisation in the country. “Thirty per cent is middle class [or rich], 70 is still very poor. I am with that 70 per cent.”

My dream for India: “I want India to be a country where people are happy and proud to be Indians, where they are equal in opportunity and well-being.”

Gail with her husband, Bharat Patankar | Amey Mansabdar

Gail with her husband, Bharat Patankar | Amey Mansabdar

Gail Omvedt, 75

Country of birth: USA

Place of residence: Kasegaon village near Pune

Profession: sociologist, activist

There are love stories. And then, there are Gail Omvedt and Bharat Patankar (67). Theirs is the kind of story that would have made a perfect script for an art movie of the 80s.

A young PhD researcher on the Black Panther movement in the US, Gail came to India to study the similar non-Brahmanical movement here. Shortly after landing in Mumbai, she was directed to Kasegaon near Pune, to meet Indumati Patankar, a noted dalit leader. No one knew then that four years later, Gail would become her daughter-in-law.

Those were exciting times, a time of political energy in the country. Back in Mumbai, Gail met Indumati’s son, Bharat, a doctor who had decided to give up his MD course in gynaecology, just short of graduation, to concentrate on social work in 1972. It was a year of drought, and the earnest doctor felt the displaced people needed his help to make use of employee guarantee schemes. Gail, too, was slowly blurring the lines between research and social work. Their paths crisscrossed and an unlikely romance blossomed.

They had a Vedic marriage, something Bharat, a dalit activist, was not too happy with. But the Emergency was on, and as he was underground, a court marriage was out of the question. They did not want to wait either, for Gail had decided to become Indian, and marriage to an Indian would expedite the paperwork. In 1982, Gail became an Indian on paper; she was Indian in spirit long before.

Over the years, she has become an authority on India’s social movements, a respected speaker and an author. She has written around ten books, he has eight major books and 50 booklets. The Songs of Tukoba, a translation of 17th century bhakti poet Tukaram, is a favourite, the only one they have collaborated on. They now want to work together on a book on the bhakti way of life.

After marriage, Gail decided to set up home with her mother-in-law in Kasegaon. She still lives in the same house; her mother-in-law is now 91. Indumati gave her an Indian name, Shalaka, which means lightning. But she is Gail (gift of God) for most. Moving from the US to a metro in India is understandable, but shifting to a village? “It was no big deal, definitely better than living in the low-income localities in Bombay where Bharat worked. Also, all of the US is not New York. In Minnesota, where I grew up, I had a fairly country-girl upbringing,” says Gail.

Different as always, they decided to educate their daughter Prachi in the Marathi medium. “It didn’t hurt her in any way, she is in the US now, co-founder of the South Asian Solidarity Initiative,” says Gail.

Gail is outspoken, never mincing her words in critiquing the country’s developmental policies even when faced with threats to her life. After social activists Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare were murdered, the couple, too, received threats. “We aren’t afraid, when you oppose power you always face threat. My parents were revolutionaries in their time. But we lodged a complaint with the police,” says Bharat. The couple have police protection, now, with constables always on duty around them.

My dream for India: “India should become more of what it is—an open vibrant society not afraid of change. I am not sure what path the country is on right now. It seems a very uncertain one.”

Tom Alter | Sanjay Ahlawat

Tom Alter | Sanjay Ahlawat

Tom Alter, 66

Country of birth: India

Place of residence: Mumbai

Profession: actor, theatre personality

If there is one thing that irritates Tom Alter more than anything else, it is asking him why he chose to become an Indian. “I did not choose,” he patiently explained. “India chose me. It is my birthright. America was never mine, it was given to me.”

The gora actor who for years has spoken accented Hindi as the gora sahib on silver screen, because the roles demanded it, is now more comfortable with the niche he has carved out in cinema and theatre, where the whiteness of his skin does not slot him anymore.

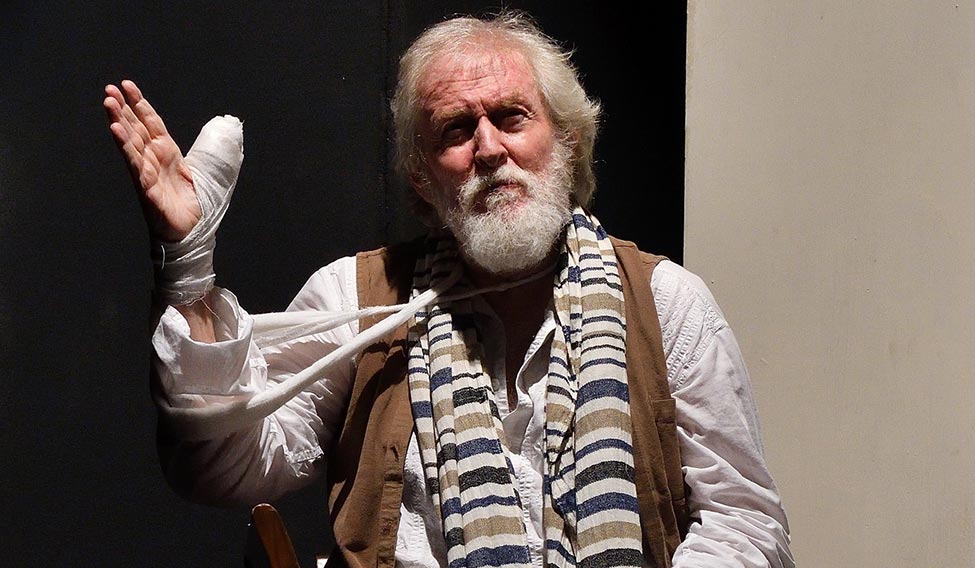

It is not easy getting in touch with Alter, who does not believe in mobile phones and checks his email intermittently. But when he came to know the topic of the interview, he fixed an appointment with alacrity. We met on a later autumn night at Shri Ram Centre in Delhi, where he was the sutradhar (narrator) in a play on K.L. Saigal. Alter had just had a surgery on his arm, and was in tremendous pain. But the stage lights were the painkiller he needed. Dressed in an intricately embroidered chikan kurta, Alter transported the audience to a morning in early twentieth century Moradabad, as he described the colour of jalebis and the fragrance of nihari. The crystalline quality of his diction made Urdu sound even richer than it is.

The Alters come from a family of American missionaries who settled in India. “We went through the same pains of partition as my grandparents decided to stay back in Pakistan,” he said. The Alters, however, kept their American passports, except Tom, who famously went to the consulate, then in Breach Candy, in Mumbai and handed it over. “They were all surprised, I wasn’t. You see, I was born in India after 1950. The Constitution says all those born in India after January 26, 1950 are automatically Indians. So I was Indian, it was only a technicality that I had an American passport because my parents were American.” Why didn’t his siblings and cousins, who also reside here, do the same? “They were born before 1950, it wasn’t their birthright, it was mine,” he said.

Doesn’t an American passport give better perks, one could not help asking, but he insisted, “It wasn’t mine.”

Alter has never felt he is gone native or is a gora babu. His best memory is going for the first show of his first film, Charas, with “yaar dost” at Yamuna Talkies in Haryana. “My dream had come true, I was an actor.”

India’s variety and richness is a source of continuous fascination for him. “Ye mulk kamaal ka hai, yahan har tarah ke log abaad hain [This is a great country, all kinds of people live here].” He, however, has a lot to say of his countrymen. “We are too worried about who is prime minister. But instead of blaming Nehru and abusing Modi and Manmohan, we should ask what we are doing for this country. We still throw fruit peels from a moving car and blame the sarkar. Gandhi was right, we need freedom from ourselves, not from the British.”

My dream for India: “I have two dreams, both of which unfortunately will not come true. I want India and Pakistan to become one again. And while that happens, I want us to stop hating each other.”

Justin McCarthy | Sanjay Ahlawat

Justin McCarthy | Sanjay Ahlawat

Justin McCarthy, 59

Country of birth: USA

Place of residence: Delhi

Profession: dancer, dance teacher

Justin McCarthy was 20 when “bharatnatyam happened to him” in California. Fascinated after watching a performance, he began training under American dancers Lesandre Ayrey and Mimi Janislauuski, recounted the Michigan born dancer of Irish ancestry. When you learn bharatnatyam, it is natural to want to visit the country of its origin, so “I came here in 1980, to Chennai”. He trained under dancer Leela Samson, and as the years progressed, he progressed from learning to teaching.

McCarthy teaches bharatnatyam at Delhi’s Shree Ram Kala Kendra, an institution he has been associated with for 20 years. “In 1995, I decided I wanted to become an Indian,” he said, though he can find no explanation for the decision. “I just wanted to. And in 1997, I became an Indian.” The process was not painful, but a long and confusing one, he said, recalling the adventures across government offices. “Ninety-five per cent of the staff was so curious. They could not understand why someone from the west would want to become an Indian. Most other applicants were from Afghanistan and Bangladesh.” It is the same question I asked him, too, and he floundered for an answer. “It’s difficult to answer. My life ended up here, and I felt I wanted to belong officially. I don’t really believe in the watertight idea of nationalities, though, but I did feel a certain happiness when I became Indian. I belong to the largest democracy in the world,” he said.

And how did life change after the change in passport? “No change really except that I got to vote,” said McCarthy, dressed in comfortable khadi attire.

My dream for India: “I wish India would rely more on indigenous solutions to its problems. We are abandoning what we were good at. Take the simple example of the ghara (earthen pot) to provide cool water in summer. We now choose more complicated methods when we had simpler answers.”