Another winter has descended over Maryland. The leafless trees silhouetted against the sky remind me of the fragile, raised hands of an old woman I saw at a church in Washington, D.C. a few days ago.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) campus at Bethesda in Maryland has too many trees to count. “Some of them flower in the spring and they absolutely change colour in the fall,” says Catherine Y. Spong, acting director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at NIH, as she shows me around the campus.

Spong is now preoccupied with something as fascinating as the blossoming trees: the placenta, one of the least understood organs in the human body. “Have you heard of the placenta before?’’ she asks me. Memories of those painful uterine contractions which pushed the placenta out, just when I thought ‘I was done’, are still fresh in my mind. But I never bothered to learn more about this marvel organ, as both times I was busy with the precious bundles that the nurses handed me.

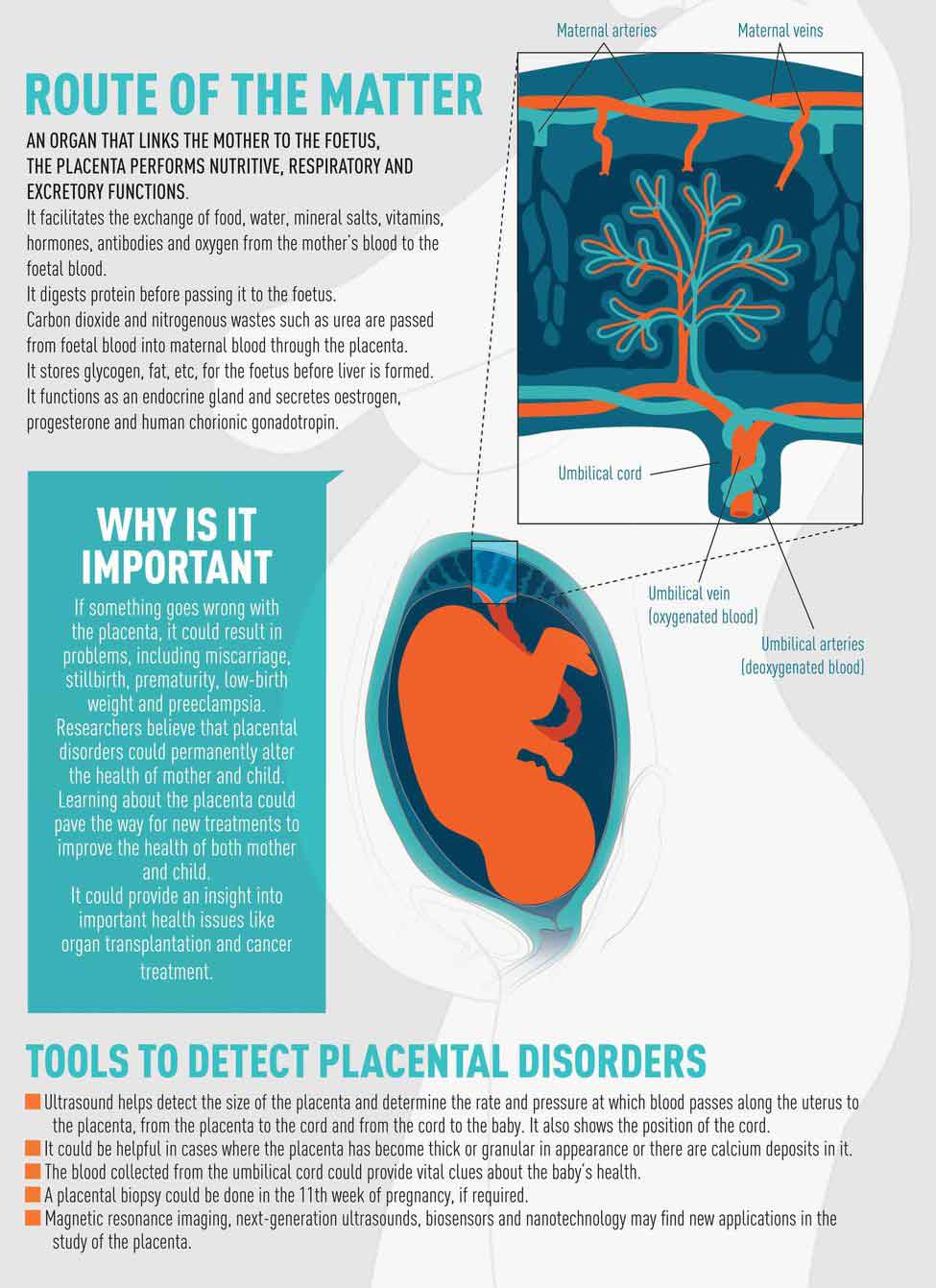

The placenta is formed along with the foetus and is attached to the lining of the uterus. It multitasks, like a busy mom, during pregnancy. “It provides oxygen and nutrients to the foetus and removes the waste products from its body,’’ says Spong.

The placenta plays a crucial role in foetal development and the maintenance of pregnancy. “It functions as the foetus’ lungs, liver and kidneys and gastrointestinal system,” she says. “Some of the hormones like oestrogen, progesterone, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and human placental lactogen (hPL), which are vital for the maintenance of pregnancy and foetal development, are also produced by the placenta.’’

Unravelling a marvel: Catherine Y. Spong at NIH.

Unravelling a marvel: Catherine Y. Spong at NIH.

Most of what is known about the human placenta comes from studies done after delivery when its function is over. “This is akin to studying the heart after it has stopped beating,’’ says Spong. Researchers at NIH are trying to fill the gap. Its Human Placenta Project aims at developing new tools which would enable noninvasive real-time in vivo monitoring of the placenta during pregnancy to understand its functioning better. “We are also trying to develop noninvasive markers to predict pregnancy outcomes,’’ says Spong. “Cells of the placenta and the foetus can be found in the mother's circulating blood. We will use them to evaluate how the placenta is functioning.’’

It could go a long way in detecting and treating placental disorders. “If such tests are available, then nothing like it,’’ says Dr Indira Hinduja, Mumbai-based gynaecologist, obstetrician and infertility specialist, who is credited with delivering India’s first scientifically documented test tube baby. “Right now, we don’t have very effective tests to check the placental function.”

Developing interventions to prevent placental abnormalities is one of the major goals of the Human Placenta Project. Dr Anita Kaul, foetal medicine specialist at Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals in New Delhi, says she is not too happy with the existing diagnostic tools and treatments available for placental disorders.

Graphics: Binesh Sreedharan

Graphics: Binesh Sreedharan

Her patient Suman Mishra was diagnosed with placental mesenchymal dysplasia, a rare developmental disorder of the placenta. “It could cause foetal growth restriction. In such cases, the foetus may not survive as it doesn’t get enough nutrients from the placenta,’’ says Kaul. “Every time Mishra comes for a check-up, I worry whether I’m going to see a baby which is no longer alive. Any minute, she may lose her baby.’’

Mishra, however, hasn't given up hope. A software engineer, Mishra, 25, follows the doctor's instructions religiously. She is now in the seventh month of her pregnancy and hopes to deliver a healthy baby at the end of her term.

Kaul often wishes she had a better understanding of the placenta so she could help patients like Mishra. At the moment, our knowledge of the placenta and its functions is so inadequate, she says. “The ultrasound and the hormone assessments are crude diagnostic tools. It is like throwing a massive fishing net out in the sea, thinking you might catch something. For conditions like PMD, there is no medicine,’’ says Kaul. “I’m hoping the project will give us finer tools and better solutions for placental problems.’’

NIH, one of the most renowned research centres in the world, launched the Human Placenta Project in the spring of 2014 after realising the need for an in-depth and focused research on the organ. Scientists from different disciplines took part in the workshops held at NIH in May 2014 and April 2015 to come up with an outline of the project. Various aspects like the impact of environmental pollution on the placenta and developing noninvasive monitoring tools were discussed. The third workshop will be held at NIH in April this year. Research groups in India and China have shown interest in the project. In fact, inspired by the Human Placenta Project, an independent meeting of scientists was held at Transitional Health Science and Technology Institute at Faridabad in Haryana in December last year on 'Provocative Ideas on Human Placental Biology'.

Hoping for a miracle: Suman Mishra, who was diagnosed with placental mesenchymal dysplasia, a rare developmental disorder of the placenta, with husband, Vinay Kumar Jha | Aayush Goel

Hoping for a miracle: Suman Mishra, who was diagnosed with placental mesenchymal dysplasia, a rare developmental disorder of the placenta, with husband, Vinay Kumar Jha | Aayush Goel

Professor Graham J. Burton, who began research on the placenta 40 years ago, is overwhelmed by the attention the organ is suddenly getting. “The placenta forms the platform from which all new life is built, and is critical to our life-long health,” says Burton, who delivered a talk at the launch of the project. “It is gratifying to see this amazing organ being given the research priority it rightly deserves.’’

The NIH is supporting 19 research projects on the human placenta at 17 academic institutions. Last year, it released $46 million for the same. Burton is the consultant for one of the projects this year.

But what does the project mean to the ordinary people? How far are women in developing countries like India, where maternal and child mortality remains a major concern, likely to benefit from it? “If we can understand how the placenta develops, its structure and function across pregnancy using noninvasive tools, we could develop assessments to determine if it is occurring normally,” says Spong. “If not, we could evaluate interventions to determine if we can optimise the placental development and then the outcome. This ultimately will improve both maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality. We have babies who are too small at birth or born too early. Many of these problems occur because of issues with the placenta. The Human Placenta Project, we hope, will help us understand how to get a normal outcome in such cases.’’

Hinduja, however, says that these interventions would work in developing countries only if they are reasonably priced. “Most of the women in India can’t afford the iron and calcium tablets, which the government gives free of cost. Very few of them can afford the Doppler scan, which is recommended in high-risk pregnancies to monitor the foetus’ health,’’ she says.

“Foetal cells as well as foetal DNA can be reliably recovered from the maternal plasma in the 15th week of pregnancy. Foetal chromosomal aneuploidy, including trisomy 21 [Down’s syndrome], serious and common genetic disorders such as cystic fibrosis, autosomal dominant gene disorder like myotonic dystrophy, Huntington disease, single gene disorder and ß thalassaemia can be detected,” says Hinduja. “Once these tests are established with good specificity and accuracy, they may replace prenatal diagnosis through invasive techniques like chorion villus biopsy and amniocentesis.’’

Bengaluru-based Dr Padmashree Sathyanarayana, who herself had a multiple birth high-risk pregnancy, believes in early interventions. The project looks promising, she says. A full-time mother to her twin boys, Sathyanarayana got the shock of her life when the doctor told her that the babies in the womb had a condition called Twin-To-Twin Transfusion Syndrome, that is they shared a common placenta. They had interconnecting blood vessels in the common placenta because of which the blood would flow from one twin (donor) to the other (recipient). “It is the number one life-threatening disease that could affect multiples,” she says. “It can develop during any week of pregnancy and even delivery. The severity of TTTS is determined by the size and frequency of connecting blood vessels in the placenta.’’

Sathyanarayana's foetal specialist Dr Prathima Radhakrishnan suspected TTTS following a prenatal screening. However, she confirmed it in the 16th week. “By then, one of the babies had grown smaller as the blood would flow from it to the other baby,’’ says Sathyanarayana. “Not treating the condition meant an 80 to100 per cent chance of losing one or both babies. We could not have lived with the guilt of letting them go, knowing they had a chance to make it.’’

Sathyanarayana got a keyhole laser ablation surgery—a procedure performed under local anaesthesia to seal off the shared vessels so that each foetus has an independent blood circulation—done by Professor Kypros Nicolaides on November 12, 2013, at King's College in London. Follow-up scans were done regularly in Bengaluru. The babies showed a positive response to the surgery. Sathyanarayana delivered two healthy babies at 34 weeks and 5 days. “They are now 21 months old with normal growth and development,’’ says Sathyanarayana, who has created a closed group on Facebook called TTTS Community-India.

Currently, there are only three centres—Bangalore Fetal Medicine Centre, Apollo Centre For Fetal Care in New Delhi and Mediscan Systems in Chennai—in India that offer laser ablation surgery for TTTS. Sometimes, TTTS is not diagnosed and a baby may die during pregnancy or delivery. The placenta project offers hope for such babies. “By having a better understanding of placental function and development, we hope to get an insight into why TTTS occurs and develop interventions to determine if we can successfully improve outcomes,’’ says Spong.

Leaving it to nature: Reba Paul opted for lotus birthing, where the umblical cord is left uncut, when her daughter Eva was born | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Leaving it to nature: Reba Paul opted for lotus birthing, where the umblical cord is left uncut, when her daughter Eva was born | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

As part of the Human Placenta Project, the researchers would look at a wide range of technologies, including the ones that haven’t yet been applied to the placenta, besides new technologies still under development, says Spong. “Nine of our projects are MRI-based, six are focused on ultrasound, four use blood analysis, and one is on near infrared resonance spectroscopy. We are also interested in the potential of biosensors, nanotechnology and other emerging technologies to assess placental cells and the products the placenta secretes into maternal circulation,” she says.

M. Suneetha, 34, of Matheru in West Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh doesn’t know anything about the role placenta plays in foetal health, even though she is a second-time mother. She developed high blood pressure during her first pregnancy and went into premature labour to deliver a preterm baby at 34 weeks. “The baby could not survive as it was suffering from intrauterine growth restriction because of placental insufficiency,’’ says Dr N. Sapna Lulla, consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist for high-risk pregnancies, Ovum Hospitals in Bengaluru, who treated Suneetha during her second pregnancy.

Why did Suneetha lose her first baby? A study conducted by S.V.S. Medical College, Mahabubnagar, Andhra Pradesh, in collaboration with Malabar Medical College and Research Centre, Atholi, Kerala, can probably explain. According to the study, pregnancy-induced hypertension can cause placental insufficiency and have a negative impact on the neonatal birth weight. It was done on 100 placentas collected from the department of obstetrics and gynaecology in S.V.S. Medical College. Half of them were from healthy mothers who had full-term deliveries and the other half from mothers with preeclampsia (high blood pressure) and eclampsia (convulsions caused by high blood pressure).

Double delight: Dr Padmashree Sathyanarayana's sons had a condition called Twin-To-Twin Transfusion Syndrome, where they shared a placenta. She underwent a surgery to correct it | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Double delight: Dr Padmashree Sathyanarayana's sons had a condition called Twin-To-Twin Transfusion Syndrome, where they shared a placenta. She underwent a surgery to correct it | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

The placentas were collected soon after delivery, cleaned in tap water and fixed with formalin for about a month. The researchers also used data on the birth weight of the babies for this study. They found that the placenta of the mothers who had eclampsia and preeclampsia weighed less than those of the healthy subjects. The placenta of one of the hypertensive mothers weighed just 200gm whereas those of the healthy mothers weighed around 500gm. Babies born to mothers with pregnancy-induced hypertension had low birth weight. The findings of this study were published in the Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine.

The Human Placenta Project, which focuses on the placenta during pregnancy, could go a step forward and open up surprisingly new spheres of knowledge for the scientific community. It could provide fresh insights into cancer biology. Over the course of pregnancy, the placenta follows a highly coordinated and complex developmental programme, says Spong. “The placenta invades the mother’s uterus, grows into her vessels and modifies her uterine spiral arteries to regulate the blood flow and pressure to suit the needs of the foetus,” she says. “It undergoes extensive vascularisation to develop the branched structures that allow for efficient transport of nutrients and oxygen between the maternal and foetal blood supply. This cellular invasion is highly controlled so that it does not penetrate too far into the uterine wall. At some point it stops and no longer takes over the vessels. In the process, the invading trophoblast [cells forming the outer layer of blastocyst that provides nutrients to the embryo and develops into a large part of the placenta] acts like tumour cells taking over the vessels. Understanding this process and its control will provide better insight into tumour biology.’’

Studies on animal placenta show that as the placenta grows, the immune cells in the local environment undergo changes. They adapt to allow the growth of the placenta and not see it as a foreign body. The researchers hope that understanding the immunology of the placenta could help in transplant, where organ rejection is an issue.

“The development and function of the placenta provide a window into a number of key physiological processes that are relevant to cardiovascular research, cancer, diseases of the immune system and transplant medicine,’’ says Spong.

Despite playing such a significant role, the placenta is yet to get the attention it deserves, even from scientists and doctors. In fact, it doesn’t even figure in antenatal care. “Little do we realise the importance of the placenta, which acts as a 'go between’ between the mother and the baby,’’ says Dr Veena Acharya, gynaecologist and foetal medicine specialist in Bengaluru.

It is time we gave the placenta its due.

Group study: Researchers at a meeting on placental biology organised by Transitional Health Science and Technology Institute at Faridabad, Haryana.

Group study: Researchers at a meeting on placental biology organised by Transitional Health Science and Technology Institute at Faridabad, Haryana.

PLACENTA AS MEDICINE

Fad or science?

By Mini P. Thomas

Celeb moms like Kim Kardashian and Holly Madison have one thing in common. They all have consumed the placenta and vouch for its medicinal properties and health benefits.

Recently, Kardashian revealed in a blog that after giving birth to her second child, Saint West, she had her placenta freeze-dried and turned into dark-purple pills, which she consumed. “I really didn’t want the baby blues and I thought I can’t go wrong with taking a pill made of my own hormones—made by me, for me,’’ wrote Kardashian, 35, a reality TV star, who believes that the placenta could help speed up the healing process.

While Kardashian preferred her placenta in the pill form, there are others who don't mind having it cooked like a piece of steak or turning it into a smoothie.

Indians generally don’t eat the placenta. However, obstetricians say that sometimes mothers do ask for their placenta. They believe that rubbing it on the baby will make the baby fairer. In fact, products for anti-ageing, depression and inflammation that contain placental elements are available in India.

“The placenta is used to treat diabetic foot ulcer, too,” says Dr Indira Hinduja, Mumbai-based gynaecologist, obstetrician and infertility specialist. “Many people believe that the placenta, especially the membrane, can heal non-healing ulcers.”

However, there is no evidence to support the belief that placenta has medicinal properties, says Hinduja. “Before you use the placenta on humans, you should make sure that it is not infected with HIV or some other infections,” she says. “I never prescribe such products because I’m not sure that they have been tested properly. I haven’t seen any improvement in the condition of people who use these products.’’

The pharma companies may be keen on cashing in on the placenta's medicinal properties, but mothers are looking at the long-term benefits it could provide to the baby. Reba Paul, a freelance writer based in Bengaluru, opted for lotus birthing—one where the baby’s umbilical cord is not cut after birth, but allowed to detach on its own, a few days later—because she felt that her baby's body could decide when to let go of the placenta. Says Paul, “It was not a difficult choice to make since there is much evidence to show that delaying the cord-cutting makes for a healthier baby.”