For Srinivas H.B. of Bengaluru, the left side of his world doesn't exist.

The 58-year-old poultry farmer overlooks the fresh flowers on the table next to his cot. He doesn't watch TV as the scenes on screen look incomplete. If you give him a thali, he tends to eat only the dishes on the right side of the platter. The picture of a rabbit he copied from a colouring book is headless!

Why are things on the left half of Srinivas's visual field always missing?

“Srinivas is suffering from a condition known as hemispatial neglect,” says Dr Anuradha H.K., consultant neurologist at Aster CMI Hospital, Sahakara Nagar, Bengaluru, who is part of the team that treats him. “It is a kind of attention disorder that occurs following a stroke or injury to the right parietal lobe in the brain, one of the higher processing centres of sensory inputs,” she says. Srinivas went about in a fog after he had a stroke in May.

Patients with hemispatial neglect may have perfect vision and hearing. However, they are not able to pay attention to or respond to the sensory stimuli on their neglected side. In one study conducted by neuropsychologist John C. Marshall and Peter W. Halligan of Cardiff University, a patient with hemispatial neglect was shown two similar drawings of a house, with one having red flames on its left. The patient did not report having seen the fire. But when asked which house she would like to live in, she always chose the one that was not on fire. Several other similar studies have shown that in people with hemispatial neglect, the sensory information from the neglected side does reach the brain. But, as they are not able to attend to it, it gets filtered out. Hemispatial neglect can drastically affect a patient's quality of life, with some ignoring not just the sights but other external stimuli like sound and touch as well.

Srinivas H.B. of Bengaluru suffers from hemispatial neglect, a kind of attention disorder that occurs following a stroke or injury to the right parietal lobe in the brain.

Srinivas H.B. of Bengaluru suffers from hemispatial neglect, a kind of attention disorder that occurs following a stroke or injury to the right parietal lobe in the brain.

Anuradha remembers a patient with hemispatial neglect who disowned his body and believed that he didn't exist. Another patient had difficulty walking. He would often bump into objects on his left side. “It happens when the brain neglects the stimuli, as a result of which the patient is not able to pay attention to the sensory inputs,” she says.

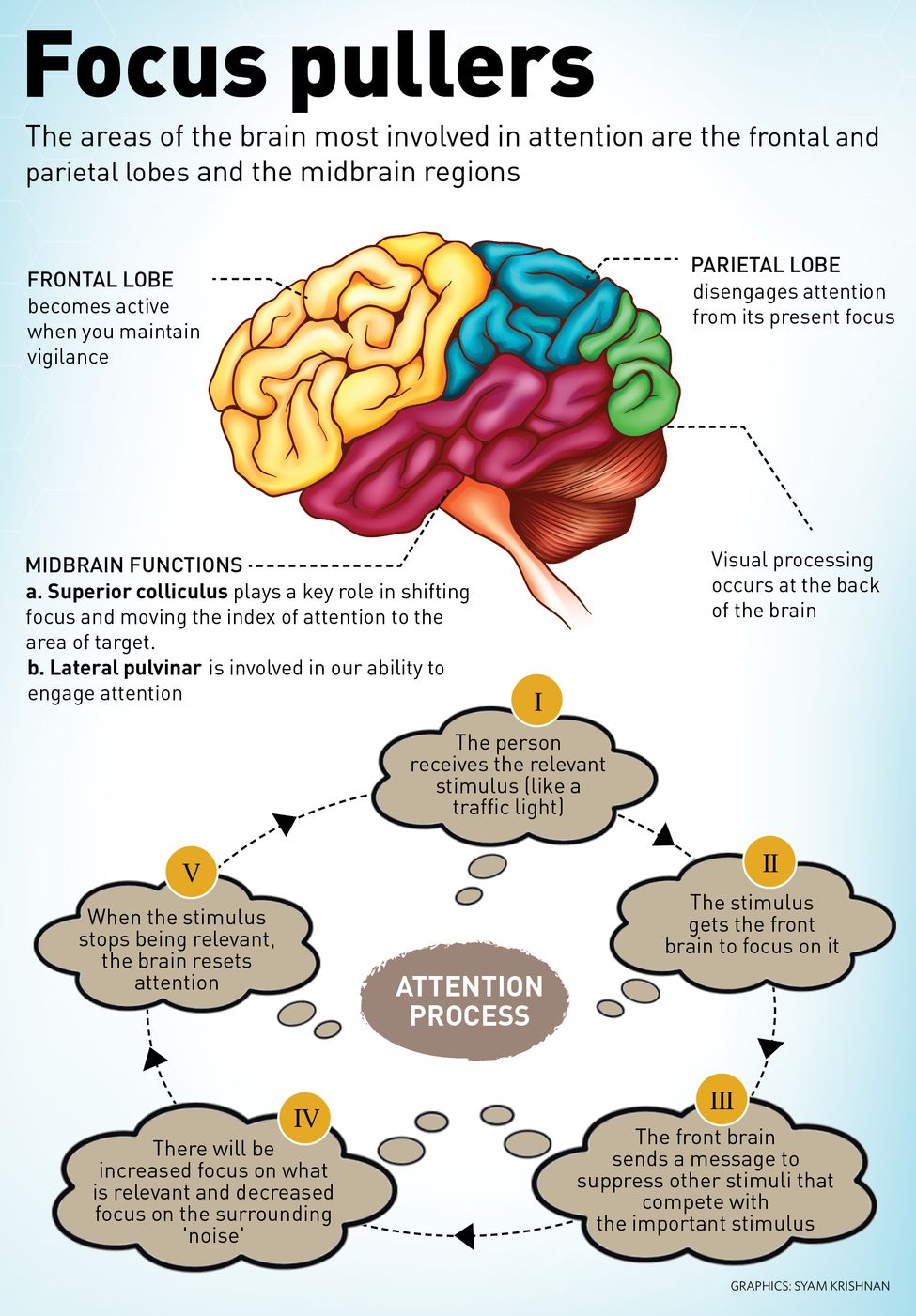

Attention is one of the most significant and yet taken-for-granted brain functions. The cognitive mechanisms that allow us to screen the sensory inputs and let in only what is important or relevant involve several brain areas. “Simply explained, attention is a series of effects that starts with the person perceiving a relevant stimulus, like a traffic light or an italicised word,” says Dr Achal Bhagat, senior consultant, psychiatry and psychotherapy at Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals, New Delhi. “Such a stimulus gets the front of the brain to focus on it. The front of the brain then sends a message to suppress other stimuli, which competes with the first stimulus. So, there will be increased focus on what's relevant and decreased focus on surrounding 'noise'. Once the stimulus stops being relevant and there is no further need of it, the brain resets attention.” In people with conditions like hemispatial neglect, these brain mechanisms are found to be impaired.

Imagine you are watching a video clip of M.S. Dhoni hitting six at the 2011 World Cup. You see the white, round ball moving in a particular direction. Our brain has different regions to process colour, shape and motion. However, when you pay attention to a moving ball, you don't feel that a lot of things are being processed at different brain regions simultaneously. You just have a unified perception of a ball flying through.

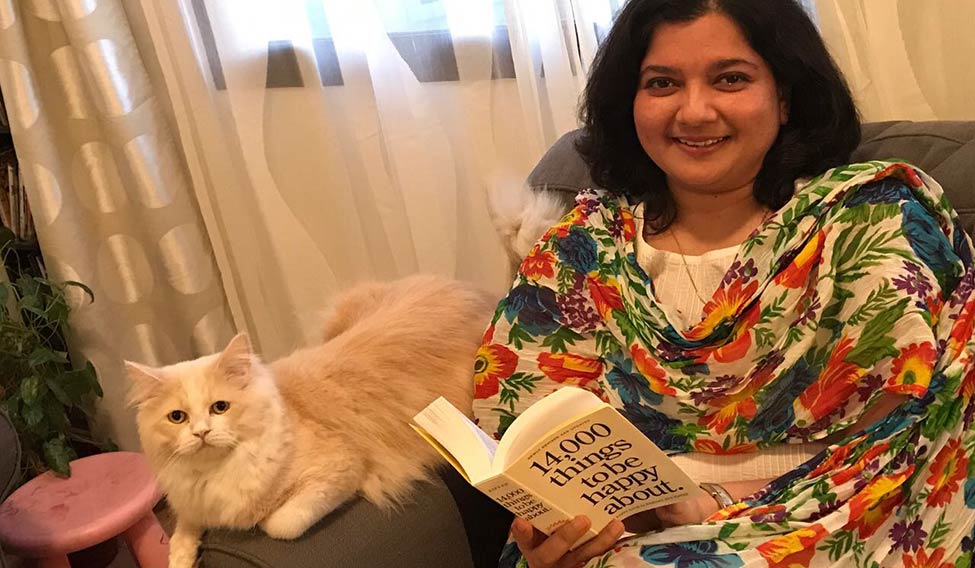

Reshma Das John attributes her photographic memory to the concentration she deploys while storing data in her brain.

Reshma Das John attributes her photographic memory to the concentration she deploys while storing data in her brain.

Being alert, attentive and mindful improves sensory processing. Attention is a core cognitive ability, without which other cognitive functions are not possible. “The capacity to attend to something is pivotal to the use of other cognitive functions like memory, language, talent development and decision making,” says Bhagat.

Reshma Das John, 42, attributes her photographic memory to the concentration she deploys while storing data in her brain. “I can remember large tracts of text in one read,” says John, who graduated in commerce from Kerala University with a third rank. Days before exams, she would happily watch movies while her hostel mates would be busy studying. Now a lecturer at the Higher Colleges of Technology, United Arab Emirates, John is a favourite of her students, thanks to her ability to remember and instantly recall their names soon after they have introduced themselves. “I use a tremendous amount of concentration to achieve this,” she says.

What does it take to achieve monk-like focus, especially when you are constantly surrounded by a cacophony of sounds?

Nivritti V. Dhruve | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Nivritti V. Dhruve | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

It is important for everyone to learn to survive in a noisy, distracted world, says Nivritti V. Dhruve, an assistant curator at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Bengaluru. Sitting under a tree with a bunch of kids, the 24-year-old seems to blend in seamlessly with her aesthetic surroundings. “Your environment sets the mood for everything,” says Dhruve. “It is easy to focus and practise meditation in a space that is green, quiet, and with an open sky for a roof. But, to me, the real challenge is when you are in your workspace, trying to do something and have all sorts of people coming and talking or someone's phone ringing to the tune of a cliched French song at its loudest. However, over the years, I have learnt the art of putting all my senses to one task.”

And, that helps her while painting, too. “When attempting to paint, all I see are the colours and patterns,” says Dhruve, who is now working on a stained glass painting. “We live in a society and space where we cannot completely shut things out. So I accept the distractions and gently bring back my focus to the task at hand.”

Dhruve's days are jam-packed. “We have a guided museum tour to take up, a workshop to complete, some research to work on and calls or inquiries to respond to via mail/phone,” she says. A monotasker, she takes up only one task at a time, works on it mindfully and then moves on to the next one. Monotasking helps you save a lot of time, she says. “The more mindful you are, the less mistakes you are likely to make. You find yourself spending less time on the tasks eventually,” she says.

Piyush Pandey

Piyush Pandey

Neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley and psychologist Larry Rosen would agree. Their forthcoming book The Distracted Mind: Ancient Minds in a High-Tech World gives insights into how constant task-switching takes a toll on our ability to pay attention to the task at hand. The duo did extensive research, involving a comprehensive examination, on media multitasking and the effects of technological interruptions on our brain. “Media multitasking is not your brain performing two tasks simultaneously, but instead rapidly switching from one task to another,” say the authors. In the digital era, there is no escape from it “as people expect real-time answers no matter what we are doing at the moment”. Unfortunately, our brains are not designed to handle such mindless multitasking. The book offers interesting tips on how to stay focused while being bombarded by digital interruptions.

Indian researchers have made much headway in understanding the brain mechanisms of attention. Dr Supratim Ray, an assistant professor at the Centre for Neuroscience, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, studies how the brain enables us to focus on a task at hand, ignoring irrelevant stimuli. He says there is a significant increase in gamma oscillations in the brain when you are engaged in an attention task. “What we found, much to our surprise, was that if you have a big stimulus, it generates not one but two gamma oscillations. That is something that hasn't been reported earlier,” says Ray.

The coordination of activity that allows you to do a complex task is reflected in these oscillatory patterns. “People who meditate generate higher gamma. Their circuits are more fine-tuned in some ways,” says Ray. “High-level cognitive mechanisms like heightened state of consciousness, learning and memory are also associated with an elevation in the magnitude of gamma oscillations. We hope our studies will throw more light on these oscillations and what they mean.” Gamma oscillations could be used as biomarkers in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia and Alzheimer's, which are associated with deficits in attention, he says. Neurons that process visual information is one of Ray's areas of interest.

At one of the labs in IISc, an attention task is underway where subjects have electrodes placed on their scalp. “That is to see how the electrical activity in the brain changes when they perform tasks,” says Ray. “We also study the effect of attention on neurons, the building blocks of the brain.”

Sridhar Devarajan, an assistant professor at IISc, uses a variety of tools and methods for his study on attention. “To understand the role of certain brain regions in attention, we turn off parts of the brain for some time. This gives us insights into how the person behaves when parts of the brain are temporarily inactive,” he says. “We also do functional MRI to record the subjects' brain activity while they are doing attention tasks, diffusion MRI to map the connection between different brain regions and EEG to measure electrical activities.” Devarajan studies the evolutionarily older and newer brain structures involved in attention. Some of his studies involve eye tracking, too, where a subject is presented with multiple tasks to see what grabs his or her attention.

Capturing attention is serious business for adman Piyush Pandey. “It is easy to catch someone's eye with outrageous stuff,” he says. “But I always take pains to know more about my audience and understand their sensibilities.”

At Aster, a team of physiotherapists and rehabilitation therapists are helping Srinivas regain his lost world. “The therapy involves some simple things like copying pictures,” says Anuradha. “We are teaching him how to look at his neglected side, and are giving him tasks—read a clock, draw a flower or round table or thali with food—to make him realise what is missing. It is like training your brain or activating the neurons. Neurons regenerate and they have what's called plasticity. It is best done within three months in the event of a stroke. Srinivas has started to feel and recognise his body parts now. ”

Anuradha now hopes one of these days Srinivas will greet her with a picture of a rabbit with its head intact.