Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi has a polite and pleasing persona. But, once inside court, he is combative and tears into the opponent. As the government’s lawyer defending the National Judicial Appointments Commission in the Supreme Court, he has been at his aggressive best to prove that the collegium system deserved to be replaced by the NJAC.

With the debate in the Supreme Court over the NJAC hotting up, the government needed someone like Rohatgi to defend the commission. And defending the NJAC is not proving to be an easy task, with the court examining whether the NJAC in any way violates the Constitutional framework, and posing some uncomfortable questions.

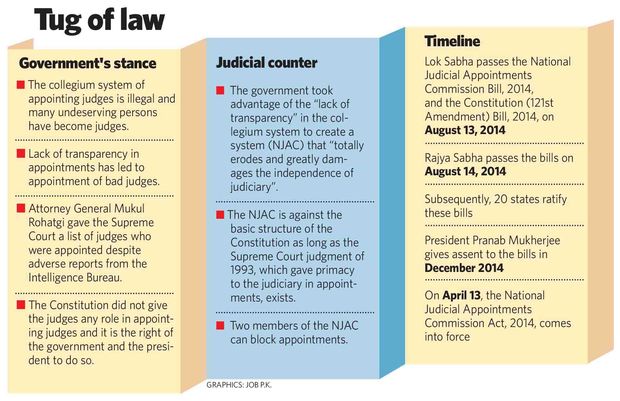

The tone and tenor of the debate has been biting, and the hearing in the matter has come to represent the tussle between the executive and the judiciary. At one point in the hearing, Rohatgi told the court that the NJAC Act, passed unanimously by both houses of Parliament and ratified by 20 assemblies, represented the will of the nation. Unimpressed, the court noted that Parliament had also unanimously passed the bill seeking to enhance the salary of Mps.

On another occasion, the five-member bench took umbrage at Rohatgi’s remark that B.R. Ambedkar would have turned in his grave considering the manner in which the judiciary usurped the right to appoint judges from the executive in 1993. The court hit back, saying, “With all that is happening, Ambedkar would have, by now, turned many times.”

The court not only took issue with the commission, but also defended the erstwhile collegium system by asking Rohatgi to give evidence of how it led to the appointment of bad judges. The attorney general came back with a list. When the court questioned his claim that Justice Cyriac Joseph had written only seven judgments in his three years as Supreme Court judge, he asked his research team to check Joseph’s record thoroughly. And he came back and told the court that he was right about Joseph.

When the court said the collegium would return if the NJAC was struck down, the government lawyers said it was gone for good. In case the Supreme Court struck down the NJAC, said the government, the lawmakers would go back to the drawing board to frame a new law.

The court, which is hearing petitions against the NJAC, including the one filed by the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association and the Centre for Public Interest and Litigation, is examining the question whether the NJAC violates the Constitutional framework.

The NJAC, a law for which was passed by Parliament in August last year, replaces the collegium system for appointment and transfer of judges. The collegium comprised the chief justice of India and four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court. The NJAC is proposed to be a six-member body headed by the chief justice and comprising two other senior-most Supreme Court judges, the Union law minister and two eminent persons.

“The NJAC law is a Constitutional amendment. So what the court is looking at is whether it violates any basic feature of the Constitution. It is not like any ordinary legislation. The court has to decide whether it has any impact on the basic feature of the Constitution; and in this case, it is the independence of judiciary,” said former Supreme Court judge K.T. Thomas.

Legal luminaries like Fali Nariman and Ram Jethmalani are arguing against the commission before the court. Nariman said the government had taken advantage of the “lack of transparency” in the collegium system to create a system that “totally erodes and greatly damages the independence of judiciary”.

According to legal experts, the judiciary cannot be expected to accept the NJAC in its present form. Former chief justice V.N. Khare said the NJAC was against the basic structure of the Constitution as long as the Supreme Court judgment of 1993, which gave primacy to the judiciary in appointment of judges, existed. “The Constitutional Amendment Bill for the formation of the NJAC did not review the 1993 judgment. So long as the judgment remains, the primacy of the chief justice of India cannot be taken away. You cannot have the judgment and the NJAC Act coexist,” said Khare.

The court asked the government to explain how the NJAC provided a better system than the collegium, raising issues such as the fact that the law minister, with the help of any one of the two eminent persons, can veto a name. Rohatgi responded that the Constitution originally did not give the judges any role in appointing judges and that it was the right of the government and the president.

“The essential point to be determined is the role of the executive and the judiciary in appointment of judges—who should have primacy?” said Ranbir Singh, vice chancellor, National Law University, Delhi. He said proponents of the collegium feel it best protects the independence of judiciary by giving control of judicial appointments to judges. “In that sense, it is not about defending the collegium. It is about the Constitutional values that the collegium is seen as protecting and the NJAC is seen as undermining,” he said.

Supreme Court lawyer Sanjay Hegde said the judiciary would be unwilling to accept a situation in which it does not have a decisive say. “In its present form, the NJAC will not pass muster,” he said. “Appointment of judges is a crucial component of the freedom of the judiciary. The argument of the government is that once the judges are appointed, they are free. But, if you appoint subservient people, you are harming the independence of judiciary.”

Critics of the NJAC say that the political class was waiting for an opportune moment since 1993, to neutralise the 1993 judgment and gain control over appointment of judges. Former additional solicitor general Vikas Singh said the judiciary could have preempted this by bringing about changes in the manner in which the collegium system functioned. “The collegium system was not a bad one. But, it was not operated properly. Had the judiciary moved in time to make the system more transparent and more inclusive, the government would not have got the pretext it needed to bring in the NJAC,” he said.

Ranbir Singh said the collegium system would return if the NJAC was struck down. Others, however, feel that the judiciary has more or less agreed on one thing—involving the government in appointment of judges, without giving up its primacy on the matter.

Unjust move

By V.N. Khare

Till 1993, the executive had primacy in appointment of judges. The system, which existed from pre-independence times, produced some eminent judges.

But, after we attained freedom, the executive lost its credibility. Nepotism and favouritism started creeping into the system. Candidates began lobbying with the law minister, the government, to become a judge.

And then, in 1993, passing its verdict in the advocates-on-record case, the Supreme Court made an interpretation of Articles 124 and 217. I do not say that the court’s interpretation was correct. It may be incorrect. But, what the court did was to interpret that ‘consultation with the chief justice of India’ meant ‘concurrence of the chief justice of India’, when it came to appointing judges.

Article 141 of the Constitution states that any interpretation of the Supreme Court is a law binding on everybody. So the court’s 1993 interpretation of Articles 124 and 217, which gave primacy to the chief justice in appointment of judges, is law.

Also, it is accepted that independence of judiciary is a basic structure of the Constitution. Appointment of judges is implicit to the independence of the judiciary. Hence, interpreting ‘consultation’ as ‘concurrence’, that you cannot appoint a judge without the concurrence of the chief justice of India, is integral to it.

In the NJAC, two nays can dismiss a name, whosoever the chief justice may be. If an eminent person, who is known to be a free man or a woman, someone who has been strict with the government, is suggested, he or she will never be appointed. The NJAC gives the executive primacy in appointment of judges.

But, the 1993 judgment has not been reviewed. The Constitutional Amendment Bill for the formation of the NJAC did not review the judgment. So long as the judgment remains, the primacy of the chief justice of India cannot be taken away. You cannot have the judgment and the NJAC Act coexist. The court can strike down the NJAC on this basis.

The collegium system was much better than the NJAC. Allow the NJAC to function for some time, and you will find that the blue-eyed boys of the government will be appointed.

The court can improve upon the collegium system. The law minister may also be included in it. The primacy will remain with the chief justice. The collegium did not have its own agency to make inquiries about prospective judges. The government should provide the court with an agency which would be under the court’s control.

The government has spoken about the collegium system appointing bad judges. But, if only less than a dozen judges, out of thousands appointed under the collegium system, were bad, you cannot say that the system is bad.

Khare is former chief justice of India.