SHIVANI (name changed) from Delhi was allegedly raped by a male acquaintance in 2012. She was purportedly given intoxicant-laced tea by the man, after which she passed out and was sexually assaulted. He threatened to make a video of the crime public if she spoke about it. However, Shivani, now 28, approached the police and a case was registered. It was assigned to a fast-track court (FTC) and the charge-sheet was filed in 2013. However, recording of evidence started only in 2017 and was listed for final arguments in early 2019. The wait for a judgment continues. The case highlights the irony of fast-track courts—set up to speed up the disposal of cases, but failing to provide timely justice.

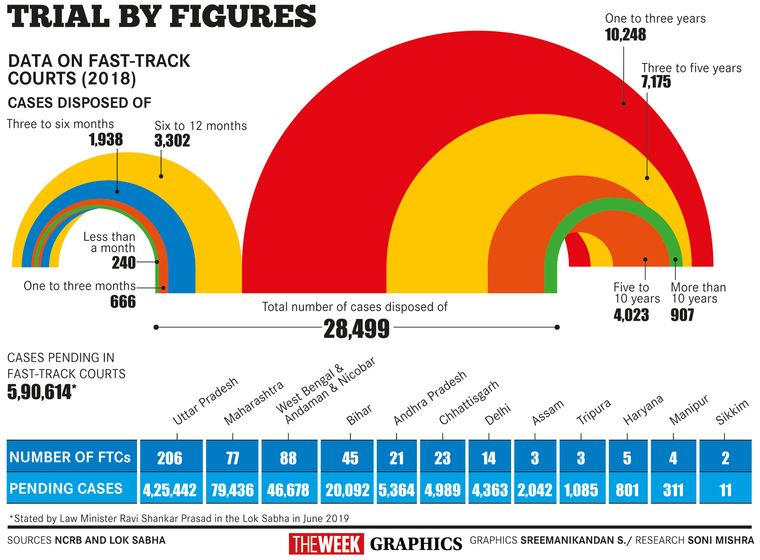

Statistics show that these courts take as long as ordinary courts, if not longer, to dispose of cases. For instance, nearly 34 per cent of the cases sent to fast-track courts in Bihar took more than 10 years to clear; in Telangana, 12 per cent of the cases went on for more than a decade. In the same duration, the lower judiciary as a whole cleared 48.75 per cent cases.

Fast-track courts are also burdened with substantial pendency. According to figures provided by the Union law and justice ministry in Parliament, as of March 2019, the 581 fast-track courts that were then operational had a sizeable pendency of over 5.9 lakh cases. Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state, had over 4.25 lakh cases pending even after the state’s 206 fast-track courts disposed of 4.56 lakh cases from 2016 to 2018.

As on December 31, 2019, 828 fast-track courts were functional. They have been set up to try various kinds of cases, primarily those relating to crimes against women and children, and also criminal cases against MPs and MLAs, mob lynchings, riots, and atrocities against scheduled castes and scheduled tribes.

Fast-track courts were first set up in 2000; the scheme was initially supposed to end in 2005, but it was extended for another six years, and after that their fate was left to the states and High Courts. The brutal gang-rape and murder of a physiotherapy student in Delhi in December 2012 gave a new fillip to fast-track courts amid a public outcry for speedy justice. A fast-track court that was set up on January 2, 2013, decided that particular case within nine months. However, as statistics show, such speed is rare.

The situation led to the Supreme Court, in December 2019, setting up a two-judge committee to monitor, supervise and make suggestions for speedy trial in cases of rape and crimes under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012. As per the law, trials in rape cases have to be completed within two months, and in POCSO cases within a year.

Experts say that problems arise from these courts being seen as a temporary arrangement; judges are drawn from the lower courts, and courts lack staff and infrastructure. “The number of judges is insufficient,” said Surya Prakash B.S., fellow and programme director, DAKSH, a civil society group that researches law and governance. “The expectation is that the judge would handle certain cases on a priority basis. But the judge is handling other jurisdictions also. So this becomes another case list for him.”

Human rights lawyer Olivia Bang said pendency of cases in the fast-track courts do not allow them to expeditiously hear matters. “Even in an FTC, the next date of hearing is often three or four months later,” she said. “And it is not surprising, since even in an FTC, on any given day, there are at least 15-25 matters listed for hearing.”

“The pace of investigation could also be one of the possible bottlenecks,” said lawyer Nimisha Menon. The Supreme Court had in 2019 observed that in more than 20 per cent of POCSO cases, even the investigation was not completed within one year. Menon pointed out that forensic sample reports are also not processed expeditiously and added that setting up labs specifically for the investigation of crimes against women and children would expedite the process.

Lawyer Eliza Rumthao, who handled one of the first POCSO cases to be registered in Delhi, said that the case, which went to court in 2012, got completed only last year. “The delay is emotionally taxing for the victim,” she said. “In many cases, the family of the victim wants to give up fighting.”

The examination of witnesses also delays matters further. Assam lawyer Bijan Mahajan, who represents the family of one of the victims in the fast-tracked Karbi Anglong mob lynching case, said: “Witnesses not turning up in the court delays the trial. And witnesses turning hostile damages the prosecution’s case.” Lawyers say that procedural changes need to be made to speed up the recording of evidence, which takes the most time in a case. “You cannot examine a witness in a day,” said lawyer Kamlesh Mishra. “Courts spend seven to eight months examining witnesses. If an alternative mechanism is devised for this, for example, if the registrar or the court commissioner is entrusted with the task of recording evidence, the disposal of cases can be expedited.”

Moreover, experts say that no specific procedure is prescribed for fast disposal of cases by fast-track courts and they have no special powers. “These courts need a different set of procedural rules and [have to be] given powers such as being able to order a probe if the investigation is found to be lacking,” said Surya Prakash.

The government had proposed the setting up of 1,800 fast-track courts for five years between 2015 and 2020 to deal with cases related to women, children, senior citizens and other vulnerable sections of society. The 14th Finance Commission endorsed the proposal that would require funds allocation of 04,144.11 crore to states. In August 2019, the Centre also announced its decision to set up 1,023 fast-track courts for disposal of pending cases related to rape and POCSO, at a cost of 0767 crore. As of January 2020, 195 of them have been set up. Out of the 1,023, 389 will exclusively handle POCSO cases, as directed by the Supreme Court.

Experts highlight a fundamental flaw in the scheme. The courts are set up under a Centrally sponsored scheme, but the task of setting up fast-track courts comes under the domain of state governments. “The scheme requires even the state governments to pitch in funds and not all the states have the financial capacity to do so,” said Tarika Jain, research fellow at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. She said that while setting a specific target of clearing 1.66 lakh cases might work for these courts, the scheme does not specify any special training for the judicial officers and it is unclear if any assistance for adequate legal representation for the parties will be provided. Such assistance can help dispose of cases in a timely and efficient manner. Jain added that no provision has been made to digitally record evidence and examine witnesses. “In sensitive cases, it might be critical for the victim to not come in contact with the accused,” she said.

According to a senior law ministry official, a decision has been taken to hire lawyers with up to eight years of practice to work as consultants to implement the scheme. They will be required to coordinate with registrar generals of High Courts to ensure that the timeline of completing the trial is followed. Also, each fast-track court will have one judicial officer and seven staff members, and no existing judge or court staff will be given additional charge of these courts.

The recruitment of judges has to be carried out by the states. But there is already an alarming dearth of judges in the subordinate judiciary, and it is doubtful how effectively the states and the already burdened High Courts will find judges for these courts.

The justification offered for setting up the 1,023 fast-track courts is that there are over 2.4 lakh cases relating to rape and POCSO pending. However, experts call for the overall strengthening and reform of the judicial system rather than trying to fix the problem of delays and pendency by setting up new fast-track courts.

There are fundamental problems with the rationale behind fast-track courts, said Alok Prasanna Kumar, senior resident fellow at Vidhi. “The idea that procedure is cumbersome and disposable in some kinds of cases is wrong and must be opposed,” he said. “And directing resources towards some kinds of cases over others creates inequalities in the system.” He said the focus should be on filling up all the vacancies in judges’ positions and providing for more judicial positions in the states where the pendency is heavy, building better courtrooms and equipping the existing judicial infrastructure, using modern technology and software for better court management, and increasing judicial budgets.

Also, while there has been a demand for speedy and time-bound justice in the wake of the Unnao and Hyderabad rape and murder cases, it is also argued that the emphasis should be on timely justice rather than speedy justice as often the timelines set for the disposal of these cases are irrational and suggest that procedure is dispensable in deciding such matters. “Skipping procedural steps in hastening a case will not stand the test of the law,” said Shubhangi, who uses only one name, programme coordinator at the Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives. “Timely trial would mean there are no unnecessary delays. And it will give the victims an experience of justice. However, there are no guidelines on timely trial by FTCs, so how can you expect these courts to be any different?”