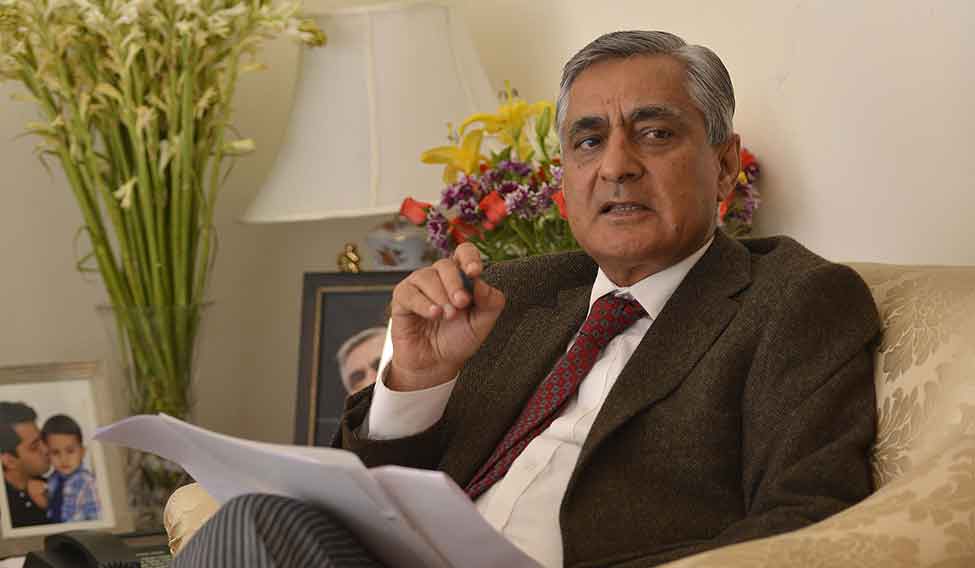

Sitting in the tastefully done up drawing room of his official residence, Chief Justice of India T.S. Thakur looks relaxed. Dressed in a brown blazer and striped trousers, he is far from being the distant and severe figure that one would expect the chief justice of India to be. Soft spoken, he assures that he speaks slowly so that there is no problem in noting down his words.

Even though he speaks softly and slowly, Justice Thakur makes a forceful case for the judiciary, explaining the reasons behind the huge backlog of cases. In an exclusive interview with THE WEEK, he says the judiciary is overburdened, with the judge-population ratio at just 12 judges per million people. About the difficult circumstances in which the judges function, he says they have to work despite poor infrastructure and dearth of support staff. And they are handling up to 150 cases a day even if it means holding court in the veranda of a ramshackle building or under a tree.

Thakur points out that many of the High Courts are functioning at 50 per cent strength and the situation took a critical turn because of the stalemate over the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). In view of the precarious situation that some of the High Courts are in, he says the collegium system of appointing judges has resumed work even before the new Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) has been put in place. On the hit list of the judiciary, he says, are cases which are more than five years old, numbering around 81 lakh. Excerpts:

The biggest challenge before the courts today is the high pendency of cases. The numbers are mind-boggling.

In the High Courts, 40,05,704 cases were pending as on June 30, 2015. In subordinate courts, it was 2,71,56,020. The total... was 3,11,61,724. Are these all arrears? You have to concede a certain time period for the disposal of a given type of case. Unless the case overshoots that period, it is not an arrear. At present, there is no determination of what should be the lifespan of a case. So, it is a wrong notion that any case pending in courts is arrears. [There is no] credible formula to determine by what time a case ought to be disposed of. No Law Commission, court or agency has decided how much time a civil or criminal case should take. There are different kinds of cases. A traffic challan can be over in 15 minutes.

Is the judge-population ratio the problem?

Two professors from the University of Cornell and the University of Chicago came here today. They said they had fixed a time period of three years for cases to be disposed of. That is a reasonable period when you look at the ratio of the judges to the population in the US. For every million people, they have 151 judges. In India, the ratio is 12 judges per million.

What would be the ideal pendency period?

On an average, three to five years is a reasonable period to dispose of a case when you look at the judge-population ratio and the lack of infrastructure in India. The number of cases which are more than a year old as on June 30, 2015 is 2,15,69,264. A gestation period of five years can be assumed as the Indian standard. Cases which are more than five years old are around 81 lakh.

How can we achieve it?

Today, we have a national court management system. The idea is to evolve standards by which the efficiency of a judge can be measured and improved. It looks at parameters such as training, timely disposal of cases, determining the optimum burden a judge can take, and how a judge can manage cases so as to increase the output. This committee is working on a target of 5+0. That means our effort will be to eliminate all cases which are more than five years old. Priority should be given to cases which are more than five years old. So the hit list is of 81 lakh cases. If we can dispose of these 81 lakh cases, it will be a great achievement. [Then] we can proudly say [we have] no cases which are more than five years old.

Is a figure of 81 lakh justifiable?

People coming to the courts and filing cases is a healthy and encouraging sign. It shows that people have not lost faith in the judicial system. In the Constitution, easy access to justice is termed as a fundamental right. There is no way one can prevent, delay, resist or obstruct access to justice.

What are the reasons for the cases piling up?

One reason is the judge-population ratio. We have ten times less judges than, say, the US. There, a judge would be dealing with three or five cases a day. In India, a judge gets 150 cases a day. The poor fellow, even if he adjourns the cases, has to write five to six lines for every case, which is 1,000 lines a day. And if he has to deliver a judgment, he has to work that much more.

Judges need better infrastructure. They need computers, training. They need a support system. There are courts which do not have stenographers; judges have to write everything in longhand. There are courts which have no proper accommodation. You have courts working out of old buildings with leaking roofs, with no litigant room or bar room. Yet, the judges keep working, even if it is by sitting in the veranda or under the shade of a tree. They are held accountable; their work is monitored by the High Court. You will not find a more responsive, responsible, effective system of monitoring than in the judiciary. Every month, a report is made on the performance of the judges.

Another thing is, there are two parties in a case, the plaintiff and the defendant. At times, the interest of the defendant lies in prolonging the matter. There is a tendency amongst litigants to prolong a case, and their lawyers seek adjournments. They make all sorts of excuses: they are ill, have a sore throat, etc. One should not forget the role played by litigants in delaying a case, and the role of the lawyer in promoting that. There must be some accountability of the lawyers. A concerted effort needs to be made to make lawyers realise that the credibility of the judicial process has to be safeguarded.

Leading lights: (From left) Union Law Minister Sadananda Gowda, Justice T.S. Thakur and President Pranab Mukherjee | Sanjay Ahlawat

Leading lights: (From left) Union Law Minister Sadananda Gowda, Justice T.S. Thakur and President Pranab Mukherjee | Sanjay Ahlawat

How many more judges do we need?

There are more than 400 vacancies in the High Courts; 1,016 is the sanctioned strength. So most High Courts are working at 50 per cent strength. For the past eight months, no appointments could be made because of the NJAC. In the subordinate courts, there are 5,000 vacancies. Together in the High Courts and the subordinate courts, the vacancies are 5,449. This is about the sanctioned strength. We need much more than what is sanctioned.

In the lower courts, in a number of states, the selection process is carried out by the Public Service Commissions. In other states, it is done by the High Court. When it is done by the High Court, the process is quicker.

When will the collegium resume functioning?

It has started. The government has to finalise the MoP under which the collegium will work. In the Meghalaya High Court, the situation was very critical. Only one judge was left. So the government has written to us to start the process on the basis of the old memorandum. We do not want a situation where we have courts without judges. We agreed with the government. While the government is working on the [new] MoP and will suggest amendments and modifications, newer vacancies will emerge and judges all over the country will be under tremendous pressure. Hence we cannot wait any longer... The process is time-consuming. There are checks within checks, wheels within wheels. A lot of verification takes place. Six to eight months are taken to clear one name. As soon as a new name gets circulated, complaints start coming. So we have to be doubly sure. The current situation is entirely on account of the stalemate between the government and the judiciary [over] National Judicial Appointments Commission.

Could this have been avoided?

It was inevitable. A constitutional amendment was made, it came to the court. Till it was not decided, the old system could not operate. It took the court six months to decide. The judges worked even during vacation [to] clear the case in record time. We knew any delay could impact the administration of justice. As the judges focused on this case, issues in other benches got affected. Today, I have got five vacancies. One more is arising in a month. The government's initiative to let us proceed with appointments has given hope. By the end of the year, there will be 500 vacancies. It is not easy to find 500 judges. The person has to be free from blemish, should have a good record of practice and a good background. The failure rate has been very low, maybe 0.1 per cent or even less. Impeachment [was] initiated only in [the case of] two or three judges. So it is an excellent ratio, a success rate of 99.9 per cent in terms of the quality of judges.

However, the expectation of people is that even this 0.1 per cent aberration should not be there. It is accepted when it is about bureaucrats or people in public life, but not judges. The expectation is that judges are men of great rectitude. Therefore, the need for greater scrutiny and circumspection.

How can pendency be brought down?

One is to have more judges and more courts. The second is to train judges so that their efficiency improves. Then, there has to be some sensitisation of bar members. They must not delay and seek adjournments. The fourth is limiting litigation by government. The government is the biggest litigant. It should not bring everything to court. The fifth issue is that deficit in governance leads to people coming to the courts with service matters and public interest matters. ADR [alternative dispute resolution] system, mediation, conciliation and arbitration should be encouraged....

Have we done anything on this?

We made a reference before the Law Commission in the Imtiaz Hussain case. We wanted to know what should be the optimum number of cases that a judge can handle. A formula has to be worked out on how many cases a judge can deal with. If the number of cases crosses that limit, the state should sanction one more post. The formula has been prepared by the Law Commission. So, from judge-population basis, we have to [move to] a judge-cases ratio. There are states with large populations but not much litigation, such as Jharkhand, which has less litigation than Kerala. So, instead of doing it on a population basis, we can do it on a more certain, more realistic basis. The court is examining that. A judicial order could be passed in this regard. On an average, it should be 1,500 to 3,500 cases per judge. Once it goes beyond 3,500, a new post can be sanctioned.

What have you done to reduce pendency in the Supreme Court?

There are many constitutional matters which are more than five years old. We will work two hours more on Mondays and Fridays when we have more space and time and take up these cases. We have already taken up some cases.