The narrow roads leading to their houses looked the same. Their houses, too, looked similar—unfinished and unplastered. Inside, their relatives sat, weeping inconsolably. Both of the murdered men belonged to the working class and to the same religion. There was just one difference between K. Mohanan and Ramit, the latest victims of political violence in Kannur, a district known for its highly volatile politics. While Mohanan became a rakthasakshi (a martyr for the CPI(M)), Ramit will be known as a balidani (a BJP/RSS martyr).

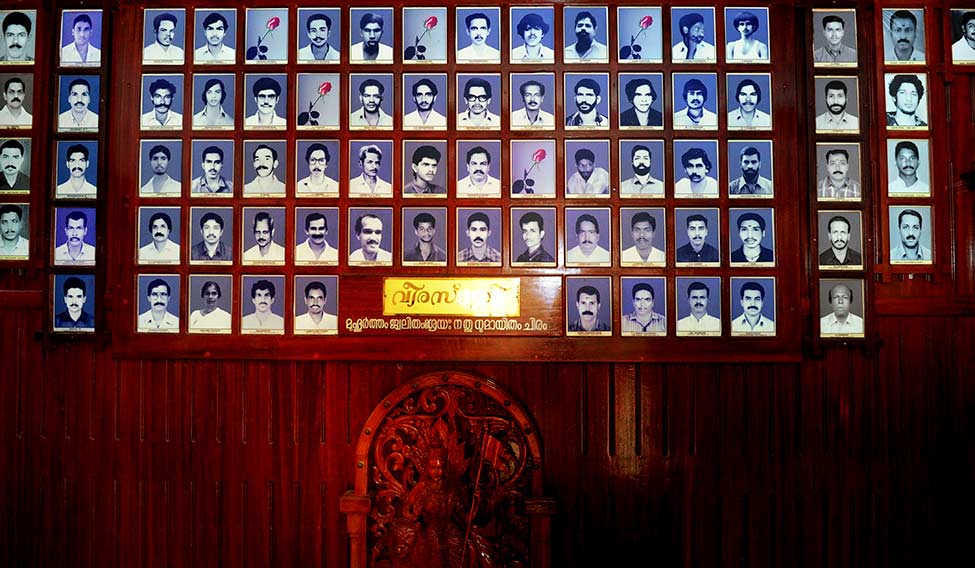

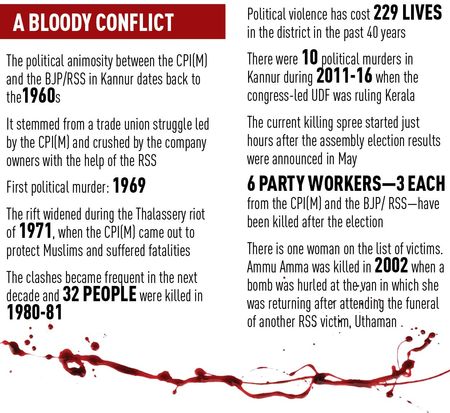

Political violence has taken the lives of 229 people so far in Kannur. After the Left Democratic Front came to power in May, six people—three each from the CPI(M) and the BJP/RSS—have been killed in political clashes. Mohanan, 50, was killed on October 10 and Ramit, 27, lost his life two days later in a retaliatory attack. Ramit was killed in Pinarayi, the hometown of Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, and Mohanan was murdered in a nearby village.

Mohanan and Ramit were the “nicest and most helpful persons” in their respective localities. “There is not a single person in our village who has not received some help from Mohanan. Still they killed him,” said Mohanan’s neighbour V.K. Rajan. He said the RSS targeted Mohanan because it realised that it would not be able to grow in the district as long as there were good people like him. Even on the day of his death, Mohanan was busy helping out his neighbour Ali with preparations for his daughter’s wedding. When THE WEEK visited Mohanan’s house, the wedding was going on, without any celebration.

The story of Ramit, the RSS victim, was eerily similar. “My son refused to leave this nasty place despite my repeated pleas. He believed that nobody would harm him as he had never hurt anyone,” said his mother, Narayani. She had lost her husband, Uthaman, 14 years ago in another bout of political violence. “They killed my husband and my son with the same sword. I have only one plea to them: please kill me with the same sword,” she cried. “I became a widow when I was 30. Since then I struggled a lot to bring up my children. If they had to kill my child, they should have finished him along with my husband. Why did they wait till he turned 27?” asked Narayani.

Tearful adieu: CPI(M) leaders consoling Mohanan’s widow, Suchithra.

Tearful adieu: CPI(M) leaders consoling Mohanan’s widow, Suchithra.

Ramit’s sister Ramisha, who is eight months pregnant, is still under the shock of having witnessed her brother being hacked to death. “My brother had just stepped out to buy medicines for my daughter. Hearing his cries, I ran out. All I saw was a man with a long sword dripping with my brother’s blood,” she said.

Fear of death has become all pervasive in Kannur. “We are scared when male members of the family step out. There is no guarantee that they will return,” said Sreela, whose brother and husband are CPI(M) workers. An RSS worker said he never took the same route to his home as he knew that he was a target.

The history of the CPI(M)-RSS clashes dates back to the 1960s. It started with a trade union strike in a bidi factory, which was crushed with the help of the RSS. The CPI(M) then started a rival bidi factory, as a cooperative initiative. The rift widened during the Thalassery communal riots in 1971 in which the CPI(M) and the RSS fought on opposite sides. Since then, violence has remained the hallmark of Kannur politics.

While the common man lives in constant fear, party leaders blame each other. The CPI(M) leadership asked Prime Minister Narendra Modi to rein in the RSS, while the BJP said the Pinarayi government was not interested in peace. “The CPI(M) does not believe in democracy and cannot stand any dissent,” said RSS leader Valsan Thillankery. He said most attacks had taken place when the younger generations of CPI(M) families moved to the BJP. “There are only two ways before us, either to surrender before the CPI(M) or to fight. We prefer to fight and we will outgrow the CPI(M) in the next ten years,” he said. It is a fact that the BJP’s vote share has shown a steady increase in the last few elections. A similar increase is there in the number of RSS shakhas, too.

O.K. Vasu Master, who left the BJP and joined the CPI(M) two years ago, said the BJP was pumping money into Kannur to destroy the CPI(M) as Kerala was a top priority for Modi and BJP president Amit Shah. “They have to defeat us in Kannur because it is the heart and soul of the CPI(M) in the state,” he said.

P. Jayarajan, Kannur district secretary of the CPI(M), said his party would not let that happen. “The fact that our government is in power will not stop us from retaliating if our comrades are touched. Image does not bother us,” he said. Jayarajan said the CPI(M) had never initiated an attack. “We only retaliate and that is something we are not shy of.”

According to observers, the average person in Kannur is innocent, hospitable and selfless. But it is exactly these qualities that the political parties exploit, said former director general of police K.J. Joseph. “And it is easy to indoctrinate them,” he said. A senior police officer from the district said political leaders from Kannur, irrespective of their ideology, displayed the same level of aggression, bluntness and devil-may-care attitude. Some attribute this to the district’s warrior tradition, commemorated in local ballads called the vadakkan pattu and the legends about Pazhassi Raja, the first local ruler who sacrificed his life fighting the British.

“Dying and killing comes naturally to the people of Kannur as revenge and a sense of honour are inbuilt in their collective psyche,” said Alexander Jacob, former police superintendent of Kannur, who now works as nodal officer of the proposed National Police University. “Suicide squads are part of Kannur’s history. People don’t think twice before killing or dying.”

The leaders are, however, proud of the district’s legacy of violence. “If you feel there is more violence in Kannur, it is because the people have the capacity and courage to react. We are not the ones who can be subjugated,” said Jayarajan, who was himself the victim of a violent attack.

Joseph, who was instrumental in curbing the political violence in the district to a large extent, said the short-term solution to the problem was to treat it as a law and order issue. “The main reason for violence is the absence of neutrality among the police and also their ineffectiveness. Give the police an absolute free hand and you will see the violence getting stopped,” said Joseph.

“I have no qualms in admitting that I tackled violence ruthlessly. But I was impartial and my image as an officer with an iron fist really helped,” he said. His actions holding the senior leadership responsible for violence, too, had helped. Joseph, however, said the long-term solution was not with the police. “If the political leadership decides, the violence will stop. It is a larger political call.”

Living in fear: Leela | M.T. Vidhuraj

Living in fear: Leela | M.T. Vidhuraj

FIRST POLITICAL WIDOW

She is Kannur’s first victim of poli-tical violence. Leela was barely 19 when her husband, Vadikkal Rama-krishnan, an RSS activist, was killed in Thalassery in 1969. This is considered the first political killing in Kerala.

Leela had got married at the age of 15. “I was very young and did not understand politics at that time. Even now I don’t understand politics. All I know is fear,”says Leela, who was initially reluctant to talk. “What is the point of talking about it after all these years? I lost everything,’’ she says.

Ramakrishnan, a 23-year-old tailor, was killed in retaliation to an RSS attack on a 16-year-old boy called Kodiyeri Balakrishnan. Currently state secretary of the CPI(M), Balakrishnan was the taluk secretary of the Students’ Federation then. “It was not a planned attack at all. It was only a retaliation,”says P. Jayarajan, district secretary of the CPI(M). Ramakrishnan died in hospital two days after the attack.

Leela continued to live in her husband’s house. “I was too young to take a decision. When my father-in-law asked me to stay back with the family, I obeyed. There were many cousins of my age... so I grew up with them,” she says.

Leela now stays with the family of her husband’s youngest brother, Sumesh, and makes a living by making banana chips and fried snacks. Life, she says, is tough and she worries for the safety of Sumesh, who is also an RSS worker. “He is like a son to me,” she says.

Sumesh travels a lot to sell the homemade chips and walks back home when he does not get an autorickshaw at night. “I find it hard to sleep even a wink until he returns home safely,’’ she says. The word fear punctuates the conversations of this soft-spoken 66-year-old.

“Many of my cousins shifted from Kannur as they are afraid of the violence here. They ask me to move in with them. But I won’t. I have nothing to lose,” she says.

Ask about the political killings, and she says: “Many people died on both sides after my husband’s death. I cry every time.... All deaths are sad.”