The lush greens of the Kowdiar palace glistened with drizzle drops. It was, perhaps, nature’s way of adding a bit of sparkle to the sparsely done-up palace, which looked more like a large house that would do with a fresh coat of paint. The 83-year-old palace breathes simplicity, like its inhabitants—one of the richest royal families in the country.

An usherer greeted me at the portico, and led me to an adjacent room. It was just another room. An old fan with tweaked wings, seen in monochrome movies, was switched on and it whirled you back into years bygone. Only the famed Raja Ravi Varma paintings hanging on the four walls stood out. The paintings are a reminder of everything that the Travancore royal family stands for—simple, subtle, austere yet dignified and classy.

Five minutes later, Princess Aswathi Thirunal Gouri Lakshmi Bayi, 72, walked in with folded hands, profusely apologising for being late. She was wearing a simple mundu and neryathu (the traditional dress of upper caste women in Kerala). No pearls or diamonds, not even a bangle adorned her, yet she looked elegant.

“Simplicity has always been our way of life. It comes from within,” said the princess who has authored several books including one on artist Ravi Varma, who was her great grandmother’s father.

The simplicity of the Travancore royals was a cause of envy for even Mahatma Gandhi. After meeting the former ruler of Travancore Sethu Lakshmi Bayi, Gandhiji said: “My visit to Her Highness was an agreeable surprise for me. Instead of being ushered into the presence of an overdecorated woman, sporting diamonds, I found myself in the presence of a modest young woman... Her room was plainly furnished and she was plainly dressed. Her severe simplicity became an object of my envy.”

Soon, Princess Pooyam Thirunal Gouri Parvathi Bayi, elder sister of Princess Lakshmi Bayi, joined in the conversation, saying, “Comfort is more important than style. Also, it makes sense to wear something light in our type of climate.”

Both the princesses attribute their simplicity to the way they were brought up. “We were brought up very frugally. Food was never wasted and we were trained to switch off the fans and lights once we exit a room,” recalled Parvathi Bayi, 75. They still lead a disciplined lifestyle—waking up early in the morning, followed by meditation and visiting the Padmanabhaswamy temple. The Travancore royals still dine sitting on the floor and eating from a plantain leaf. “That is the healthiest way to have food. Also, we don’t need to do extra exercise with all the sitting and standing up,” she said half in jest.

A renowned dancer and singer, Parvathi Bayi was the first girl from the royal family to perform on stage, much to the chagrin of the traditionalists among the royal circle and public. That was in the 1950s. She was also the first person from the family to seek employment. Soon after her studies, she started teaching French at the Kerala University. Her grandmother, Sethu Parvathi Bayi, she said, went to London when she was only 16—this, at a time when crossing the ocean was seen as sin even by men. “The women in Travancore family have always been powerful. Our lineage is such,” she said.

Taking the legacy forward: (From left) Parvathi Bayi, Lakshmi Bayi, Parvathi Bayi’s husband C. Raja Raja Varma and Lakshmi Bayi’s granddaughters | B. Jayachandran

Taking the legacy forward: (From left) Parvathi Bayi, Lakshmi Bayi, Parvathi Bayi’s husband C. Raja Raja Varma and Lakshmi Bayi’s granddaughters | B. Jayachandran

The Travancore royals are among the rare breed of royals who follow the matrilineal system. The royal lineage is never passed through the sons of the king but through the sons of the king’s sisters. This means the wife of the king is never the queen, nor his daughters, princesses. It is his mother and sisters who are queens and princesses, respectively.

This system had baffled the patriarchal west including former US first lady Eleanor Roosevelt who had visited Travancore in 1952. “Travancore follows a system where sons of the king will never become the next ruler. It is very complicated, but it is very good for women,” she wrote in Life. Agreed Parvathi Bayi: “The matrilineal system is very empowering. If the women in Kerala are more powerful and educated than the rest of their counterparts, it is because of this.” Travancore rulers used to gift diamond and ruby earrings to girls who graduated, she recalled.

“Apart from the much-celebrated female power and their simplicity, it is their modern outlook, their thrust on education and health care that makes the Travancore family really great. Their fingerprints are very much there in the making of modern Kerala,” said historiographer S. Uma Maheswari.

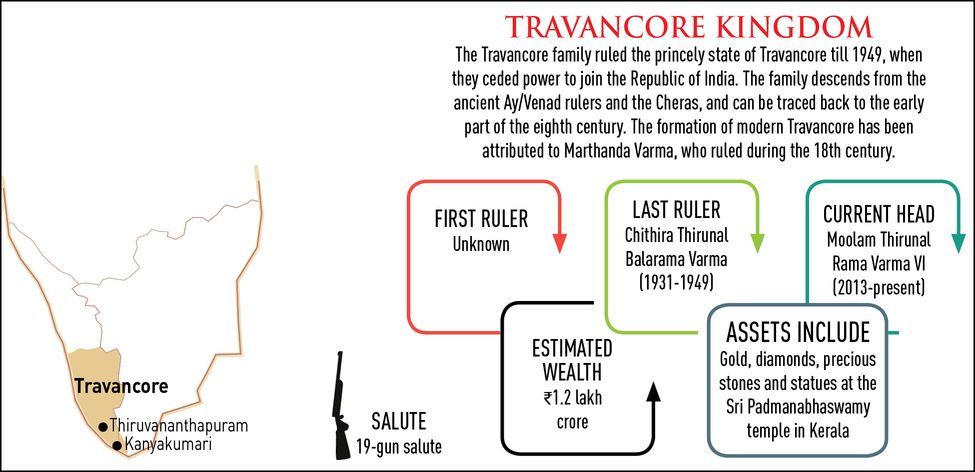

The strong secular texture of Kerala also has its roots here as it is under them that the minority communities found prominent space in public spheres. The rule of Sethu Lakshmi Bayi (reign 1924-1931) and Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma (reign 1931-1949)—considered the “golden period”—witnessed revolutionary social programmes including adult franchise, temple entry proclamation, midday meals and abolition of capital punishment (a first in India).

How does it feel to have such a legacy? “We feel so humble and proud at the same time.... We witnessed the spontaneous outpour of grief when our uncle [Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma—the then ruler of Travancore] died. The love and affection that people still have for our ancestors is so touching,” said Lakshmi Bayi. But royalty means nothing to them, she said. She insisted they lead a normal life, despite it being a bit more complicated.

This attitude is shared by the younger generation, too. Prince Rama Varma, son of Parvathi Bayi, and an acclaimed Carnatic musician, said royalty is an old notion. “I have never felt royal myself, which is one reason why I have been living away from the Kowdiar palace,” said the 49-year-old. “I prefer to be just a face in the crowd. I revel in anonymity the way many people revel in celebrity.”

Aditya Varma, 46, the youngest prince in the Travancore royal family, shared a similar sentiment. He runs a dairy farm with 20 cows on the palace premises. “I try to lead a normal life,” he said. “The only time when I feel like a royal is during the arattu [an annual procession at the Padmanabhaswamy temple, led by male members of the Travancore family].” The farm apart, the royal family owns a trading company, Aspinwall Ltd, and has assets in real estate and shares.

The current head of the Travancore family is Sree Padmanabhadasa Sree Moolam Thirunal Rama Varma, the only nephew of the last reigning king. He is married to Dr Girija Rama Varma, a radiologist who was formerly based in London. They started living in the Kowdiar palace following the death of his uncle and former king in 2013. “It is a great responsibility to live up to the heritage and tradition of hundreds of years,” said the 68-year-old, who dislikes any sort of publicity. But, he added, “Today we are all equal. We interact with every citizen of India on equal terms.”

Rama Varma rarely attends public functions except religious ones at the Padmanabhaswamy temple. But his sisters, Parvathi Bayi and Lakshmi Bayi, are an integral part of the cultural scene in the capital city, Thiruvananthapuram. The Travancore royal family was not just a great patron of art and literature but was home to legends like musician Swathi Thirunal and painter Raja Ravi Varma.

But if you ask the royals what distinguishes them from the rest, they will tell you it is their absolute surrender to Lord Padmanabha, the deity of the family temple, before whom Maharaja Anizham Thirunal Marthanda Varma, the first of the Travancore maharajas, had surrendered his kingdom.

“It is our absolute surrender before Lord Padmanabha, which is our most precious asset, and not the the temple treasures that everyone is obsessed with these days,” said both the princesses in unison.

The princesses were alluding to the controversies and court case over the ownership of the Padmanabhaswamy temple after it was found that there were hidden treasures worth Rs 1 lakh crore hidden inside. Apparently, there are gold coins dating back thousands of years, sacks full of diamonds, antique ornaments and crowns studded with diamonds and emeralds and other precious stones.

The Travancore royals, who trace their ancestry to the Chera dynasty of south India, have been associated with this temple named after Lord Vishnu for centuries. In 2010, a petition was filed in the High Court, alleging mismanagement of temple affairs. The High Court had asked the state to take over the temple, its assets and management. The royal family challenged the order in the Supreme Court, which stayed the High Court order and asked for a detailed inventory to be drawn up of all the valuables in the temple’s six vaults. It was in 2011 the “hidden treasures” became public. The case is still pending.

“It is wrong to call it hidden treasures because we always knew about it,” said Parvathi Bayi. “We never made an effort to assess and calculate its worth as we deemed it as an offering surrendered to Lord Padmanabha. We still believe it belongs to the Lord alone.”

Even as the controversy shows no sign of abating, opinions are divided. While some said the temple treasures should be nationalised, a few others said it should remain untouched as it belongs to the royals and the temple. But, like a historian, who did not want to be quoted as the matter is before court, said, “If the Travancore family wanted to take the treasures, they could have done it easily. Not a single soul would have come to know about its existence.”

The Travancore royals did not hide their disappointment in being seen with suspicion. “It really hurts when some say that the Travancore royal family, which submitted everything to the Lord Padmanabha, is trying to usurp his belongings,” said a teary-eyed Lakshmi Bayi. “At times, we feel we made a mistake of not leaving the palace like most royals did after losing their hegemony. We never tried to market our heritage with a business motive. We stayed on here because of our faith in Lord Padmanabha.”

A few silent moments later, she took leave as she had an ailing granddaughter to tend to. As she climbed up the wooden staircase, it creaked slightly. Pointing at a few misplaced furniture, Parvathi Bayi said, “All these need to be refurbished.... But now our entire energy is being sapped by the court case. Our fight is not to stake claim to the treasures but to protect our dignity and integrity.”