On February 5, at 10:30am, the special court in Kumbakonam in Tamil Nadu falls silent. S. Baskaran, the additional chief judicial magistrate, takes his chair on the podium. He goes through the case papers, his voice growing louder with each page. The case before him, of idol theft, has been transferred from the Jayankondam magistrate's court for a speedy trial. The court officer shouts the names: “Subhash Chandra Kapoor, Sanjeevi Asokan, R.K. Kumar….” Ten men enter the hall and stand in the dock. When no one answers to “Subhash Chandra Kapoor”, the court officer looks at the prosecutors and police officers. They explain that he is being brought from the Puzhal prison in Chennai, his home since 2012. The court is adjourned.

In a while, a police van enters the premises. Policemen escort a balding, fair man in his 60s, whose face is covered with a blue cotton towel. Though this was his first visit in handcuffs to Kumbakonam, Kapoor has known the temple town closely for many years. This was, after all, a major source for his colossal antique business.

The hush in the court returns. The court officer calls for Kapoor, whose small, nervous eyes dart around. “This is a high profile case and I want to dispose it soon," says the magistrate. “The trial will begin on February 19. I want the prosecution, all the accused and the advocates to cooperate.”

Within minutes, Kapoor is whisked away by the policemen. “I am not able to go out on bail because I am a foreigner [US citizen]. The idol wing [under the Tamil Nadu economic offences wing] is dragging the case and the trial is getting delayed,” Kapoor tells THE WEEK before boarding the van.

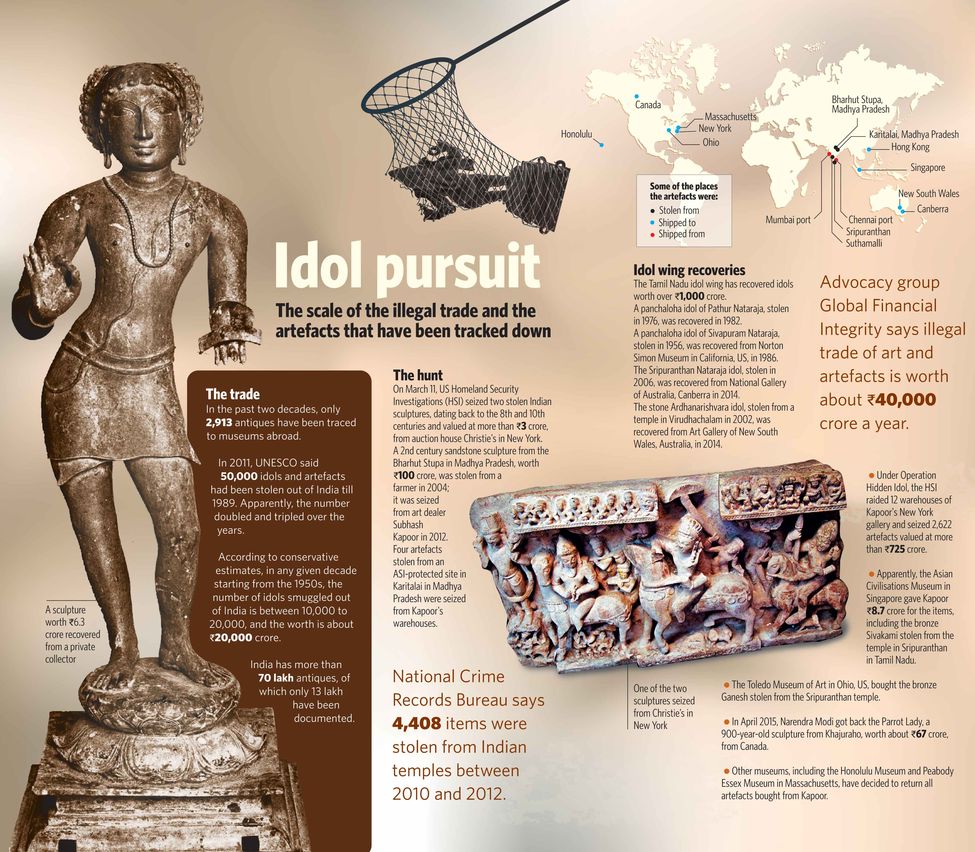

Idol wing officers, however, say the examination of witnesses has begun and the next hearing will be on March 30. And, as if to highlight the importance of curbing the illegal trade, on March 11, US Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) seized two stolen Indian sculptures, dating back to the 8th and 10th centuries and valued at more than 03 crore, from auction house Christie's in New York.

The arrest and cases

The HSI and the idol wing began investigating art dealer Kapoor nearly a decade ago. In 2011, the Tamil Nadu Police issued a warrant for his arrest and Interpol issued a red corner notice. On October 30 of the same year, Kapoor was arrested at the Frankfurt International Airport in Germany. He was then extradited to India. Two criminal cases were filed against him, with charges including burglary of temples for artefacts, forgery and falsification of records, and receiving and selling stolen property.

Local guardians: Palanisami (in checked shirt) and his wife, Amudha (sitting on the ground) take care of the abandoned Sripuranthan temple | R.G. Sasthaa

Local guardians: Palanisami (in checked shirt) and his wife, Amudha (sitting on the ground) take care of the abandoned Sripuranthan temple | R.G. Sasthaa

The temples

About 15km from the special court, in the dusty village of Sripuranthan, a muddy road leads to the ninth-century Brihadeeswara temple. A thick chain and lock hang on the closed gate. A frail, dark man emerges from a nearby hut. “Have you come to the temple? Our temple has been looted already. There is nothing else to take,” he says. Palanisamy Kasi, 42, and his wife Amudha, 38, are now the guardians of this abandoned temple. “Sivan sothu kula naasam [Stealing Lord Shiva’s property leads to destruction of lineage],” he says, opening the gate. As Palanisamy switches on an LED lamp, we see a life-sized vinyl print of Shiva on a wall. The alcove here was once the abode of the 1,000-year-old bronze idols of Shiva (Nataraja) and his consort Sivakami. The Nataraja idol, worth Rs 40 crore, has travelled from the temple to Kapoor’s storerooms in New York and to the National Gallery of Australia. In 2014, Australian prime minister, Tony Abbott, restored the idol to India.

About 10km northwest of Sripuranthan, there are two more burgled temples—the Sundareswarar Temple and the Varadaraja Perumal Temple. The former now has a broken statue with a red sari draped around it. “There is no god here. So we don’t worship here,” says Muthu Selvam, a nine-year-old student at the nearby anganwadi school. For Selvam and his friends, the abandoned temple is an ideal place to play hide and seek.

The man

The Indian-born Kapoor ran the Art of the Past gallery in Madison Avenue, New York. It specialised in Asian art and artefacts. He portrayed himself as an authority in Asian art. Educated in Asian history, he studied books on historical sites in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Afghanistan, and allegedly smuggled art and artefacts out of Asia to be sold to museums in the US, the UK, Australia and Singapore. In fact, dealing in antiquities was a family vocation. In 1971, his father, Parshotam Ram Kapoor, was indicted by Indian investigating agencies for smuggling art out of India. In 1974, the family moved from Punjab to the US. In an interview to British magazine Apollo in 2009, Kapoor said he had learned the trade from his father. “My father started to buy [art] in 1947 after he moved from Lahore after partition,” he says. “He spoke eight or nine languages. Punjab was split in two and the university was in Lahore, in Pakistan. So, my father bought old books left behind by Muslims who had gone to Pakistan and sold them to India’s new Punjab university. From there, he got into manuscripts and paintings. I was looking at these when I was five or six.”

Through his gallery and Nimbus Import Export Inc, Kapoor sold artefacts to 35 galleries around the world. And, nearly all the sales, say police sources, were through his long-time girlfriend Salina Mohamed. Also under investigation are his ex-girlfriend Paramaspry Punusamy, his sister Sushma Sareen and his daughter, Mamta Sager. Investigators say that his brother Ramesh Kapoor still deals in art and artefacts.

Prison life

Every day, Kapoor has bread, a cup of rice and five pieces of fried fish. “He goes for a morning walk every day,” says a policeman. A diabetic, Kapoor was diagnosed with prostate cancer soon after his arrest in 2011. However, police sources say he is still passionate about art, though not in the financial sense. “There is no business. My gallery is closed,” Kapoor tells THE WEEK. “This is all a put up case."

The trade

Global Financial Integrity, an advocacy group based in Washington, has estimated the illegal trade of art and artefacts to be worth about Rs 40,000 crore a year. And, Indian idols are much in demand. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, 4,408 items were stolen from Indian temples between 2010 and 2012. In the past two decades, only 2,913 idols and antiquities have been traced to museums abroad. In 2011, UNESCO estimated that 50,000 idols and artefacts had been stolen from India till 1989. The number, apparently, doubled and tripled over the years.

According to conservative estimates, in any given decade starting from the 1950s, the number of idols smuggled out of India was between 10,000 and 20,000, and the worth was about Rs 20,000 crore. “Next to human and drug trafficking, art is the most profitable business,” says Prateep Philip, additional director general of police, Tamil Nadu’s economic offences wing.

Under its search mission (started in 2009 and named Operation Hidden Idol in 2011), the HSI raided 12 warehouses of Kapoor's New York gallery and seized 2,622 artefacts, which were valued at more than Rs 725 crore. Notably, this was just the stock in known locations and the gallery had been in business for 35 years. In 2014, along with the Nataraja idol, Abbott had returned a granite sculpture of Ardhanarishvara (the androgynous form of Shiva), which had been stolen from a temple in Virudhachalam, 61km from Suthamalli. In June 2015, Indian authorities traced 30 objects seized from Kapoor to the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. Apparently, the museum gave Kapoor Rs 8.7 crore for the items, including the bronze Sivakami stolen from Sripuranthan. The Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, US, bought the bronze Ganesh idol stolen from the Sripuranthan temple. In April 2015, Narendra Modi got back the Parrot Lady, a 900-year-old sculpture from Khajuraho, worth about Rs 67 crore, from Canada. According to ongoing idol wing investigations, about 240 objects seized from Kapoor have been traced to various museums around the world.

Museums such as the Honolulu Museum of Art and Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts have decided to return all the artefacts bought from him. They say almost every object that passed through the gallery had been looted. New York-based art dealer Nancy Wiener sold a Kushan Buddha statue to the Australian government. Wiener later gave a full refund as the statue had a dodgy provenance (record of ownership) and she has agreed to return it to India.

Individuals are not the only ones profiting from this illegal trade. Apparently, Islamic State has been looting heritage sites in Iraq and Syria and selling the stolen items in Britain.

Graphics: N.V. Jose; Research: Lakshmi Subramanian

Graphics: N.V. Jose; Research: Lakshmi Subramanian

Modus operandi

According to the idol wing, Kapoor, though a seasoned antique smuggler, was not familiar with the temples in Tamil Nadu and it was only in September 2005 that he visited some of the temples.

In 2006, through a network of art dealers, he met Sanjeevi Asokan and told him about the huge price art collectors abroad were willing to pay for old bronzes. “This association ultimately led to thefts in the two temples in Sripuranthan and Suthamalli, from where 28 panchaloha idols were burgled,” says Philip. In 2006, he says, Kapoor gave Asokan his first advance. Asokan allegedly hired local thieves and paid them Rs 7 lakh to break into the Sripuranthan temple and steal the bronze Ganesh idol (now at the Toledo Museum) and seven other idols, including the Nataraja idol. To mask the value of the idols, they were sent to the US along with several fakes. The consignment was sent through Nimbus Import Export Inc, and Asokan was paid about Rs 4 crore from Kapoor’s HSBC account in New York.

“We were told that there were large beehives and killer bees inside the temple,” says Palanisamy. “The door itself had worn out and there were large thorny bushes. None of us ventured into the temple. One fine day, when we cleared the bushes and opened the temple by pooling in money from the villagers, the idols were missing. This is when we informed the Hindu religious department authorities.”

Every time such artefacts reached Kapoor, he would obtain a certificate from Art Loss Register (ALR), a private company in London that maintains a database of stolen or lost art. In the art world, a certificate from ALR is accepted as proof that the artefact is free from claims, even if it isn't, as was the case with Kapoor’s art pieces. The company relies only on information provided by the person seeking the certificate, which, in several cases, is not authentic. The certificate with regard to the Sripuranthan Nataraja idol says: “This certificate is no indication of the authenticity of the item; the ALR does not guarantee the provenance of any item against which the ALR has made a search.”

In the case of the Nataraja idol and the other items stolen from the two villages, Kapoor had allegedly prepared a fake provenance in the name of a Raj Maghoub, wife of Sudanese diplomat Abdullah Maghoub, who had been posted in New Delhi between 1968 and 1971. Dated January 15, 2003, the provenance stated that the Nataraja idol had been out of India since 1971, a year before the 1972 Antiquities and Art Treasures Act was enacted.

To make the provenance more credible, Kapoor allegedly fabricated a bill dated May 14, 1970, from Fine Art Museum, an art dealer in Delhi, showing the sale of the Nataraja idol to Abdullah Maghoub. The provenance said that, after Abdullah's death in 2004, the ownership was transferred to his wife, who sold it to Kapoor. He then displayed the Nataraja at his gallery, from where the National Gallery of Australia bought it.

Jason Felch, author of Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World's Richest Museum, says, “The National Gallery of Australia filed a $5 million [Rs 33.5 crore] lawsuit against Kapoor, alleging the dealer and his staff committed fraud when they sold the museum an 11th century bronze sculpture of Shiva that had been stolen from an Indian temple.” The lawsuit, filed on February 5, 2014, in New York’s Supreme Court, alleges Kapoor and his manager Aaron Freedman, “fraudulently induced the NGA to acquire the Shiva by making misrepresentations and false assurances concerning the history of the Shiva”.

Kapoor, however, is not alone in this business. In 2003, Jaipur-based art dealer Vaman Narayan Ghiya was arrested, He confessed to have stolen and exported more than 10,000 pieces of art. His loot, amassed in the 1980s and 1990s, was estimated to be worth about Rs 6,700 crore.

Why the loot

Says private investigator and avid blogger Vijay Kumar: “The market for antiquities is fuelled by the US dollars.” His blog Poetry in Stone has details about idol theft cases and he was instrumental in Kapoor's arrest in 2011. He alerted the idol wing which, with his help, began the investigation that led to the arrest.

Experts play a huge role in making artefacts marketable, which helps art dealers continue their trade. For instance, several Padma Shri awardees have written for Art of the Past, and many historians have used items from dealers in their publications and shows, thereby lending credibility to the dealer and the art. This was mentioned in the due diligence report submitted by the Australian gallery to its culture minister.

The richness of Indian artefacts is the main lure. The Chola period sculptures, or the panchaloha idols, have been in demand because of their mix of five metals—gold, copper, silver, iron and lead. In some cases, tin or zinc is used.

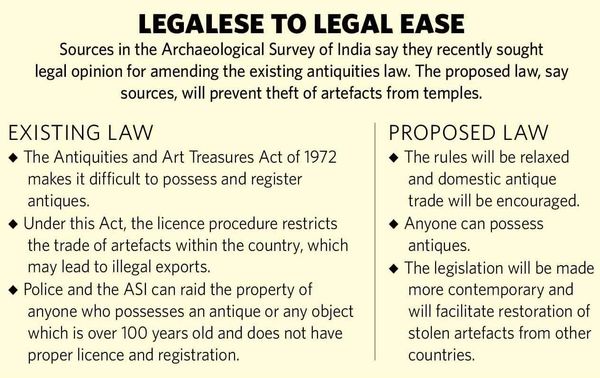

Many blame the government’s apathy for the loot. The Archaeological Survey of India does not maintain a record of artefacts. Though it files first information reports in cases of theft, there is no mechanism to oversee the on-ground situation. The Comptroller and Auditor General, in a 2013 report, said: “The ASI had never collected information on Indian antiquities put on sale at Sotheby’s and Christie’s as there was no clear provision in the Antiquities Act, 1972 to do so.”

The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972 has no enforcement powers. The National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities, a government agency launched in 2007 to prepare a database and preserve India’s heritage sites, is still not clear about its mandate. It has documented only 13 lakh objects while there are more than 70 lakh antiquities in India. Says Kirit Mankodi, a Mumbai-based professor of archaeology: “India does not have a proper national archive of its cultural treasures, nor does it make any attempt to publicise or update loss registers, even those available for free, like Interpol's stolen works database.”

Also, the ASI currently has no enforcement powers, which, say experts, are crucial to curbing art thefts. For instance, the Carabinieri Art Squad in Italy, which is a specialised police wing, has been hugely successful in reducing art-related crime.

Lost heritage: The temple in Suthamalli, from where many idols were stolen | R.G. Sasthaa

Lost heritage: The temple in Suthamalli, from where many idols were stolen | R.G. Sasthaa

The temple authorities, too, are at fault for not documenting the treasures and for not reporting thefts. The Tamil Nadu government's Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department, which maintains 35,000 temples, does not have a record of the number of bronze idols and stone sculptures in the older temples. For instance, the Sripuranthan temple remained locked for several years, and no official came to document its sculptures.

Says the CAG report on Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities: “There is a need for a more concerted approach for retrieval of Indian art objects stolen or illegally exported to other countries. The ASI as the nodal agency for this purpose needs to be more proactive in its efforts and the ministry needs to develop an aggressive strategy for the same.”

Even in Kapoor's case, though the Homeland Security Investigations seized 2,622 objects from his warehouse, only 18 idols have been mentioned in the two cases registered by the Tamil Nadu police.

India has never pushed for any notable restitution. In fact, between 2000 and 2012, not a single artefact was returned to its original owner. “This is why Indian art is fair game,” says Vijay Kumar. In Kapoor's case, the Tamil Nadu idol wing wrote several letters rogatory to Australia and the US. It has also recently written to the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore to retrieve more than 13 artefacts and idols.

Vijay Kumar saw the sloth in the system when he tried bring back the Ganesha from the Toledo Museum with the help of the idol wing. “We have letters from the Toledo Museum Ohio which, after our initial contact, wrote to the Indian consulate and to the Indian ambassador in the US and did not get a response for six months, and finally handed over the objects to US customs instead,” he says.

What is most baffling is the reluctance to recover the National Gallery of Australia’s acquisitions, which have all been proven to have fake provenances. “The artefacts have been taken off display, but there is still no attempt to seek their return,” says Anuraag Saxena, an Indian art blogger. Moreover, the recovered items don't find their way back to the temples. For instance, the Nataraja idol is kept at the icon centre of the Nageswaran temple in Kumbakonam.Another problem is the absence of any reward for a customs official who seizes an artefact.

INDIA, SAY EXPERTS, needs a highly trained national art recovery squad consisting of experts in criminal and art law, cyber technology and art in general. Sadly, India has taken only baby steps in this regard. The two main departments—the Tamil Nadu idol wing and Kerala's State Temple Anti-Theft Squad—are poorly staffed and are seen as punishment postings.

Also, there seems to be no will to bust the criminal network. In most cases, only the petty thieves are caught. For instance, Kapoor had shipped artefacts to a company in Hong Kong, which sent them to a professional art restorer in London. “No attempt has been made to pursue these leads for criminal intent. In fact, the names of the company in Hong Kong and Neil Perry-Smith company in the UK have been dropped from the case,” says Kumar.

Back in prison, Kapoor blames the idol wing for dragging the case; he wants to go home. So do the 2,622 artefacts seized from his gallery.