We have not inherited this earth from our forefathers, but borrowed it from our children. —Moses Henry Cass (environment minister of Australia in the 1970s)

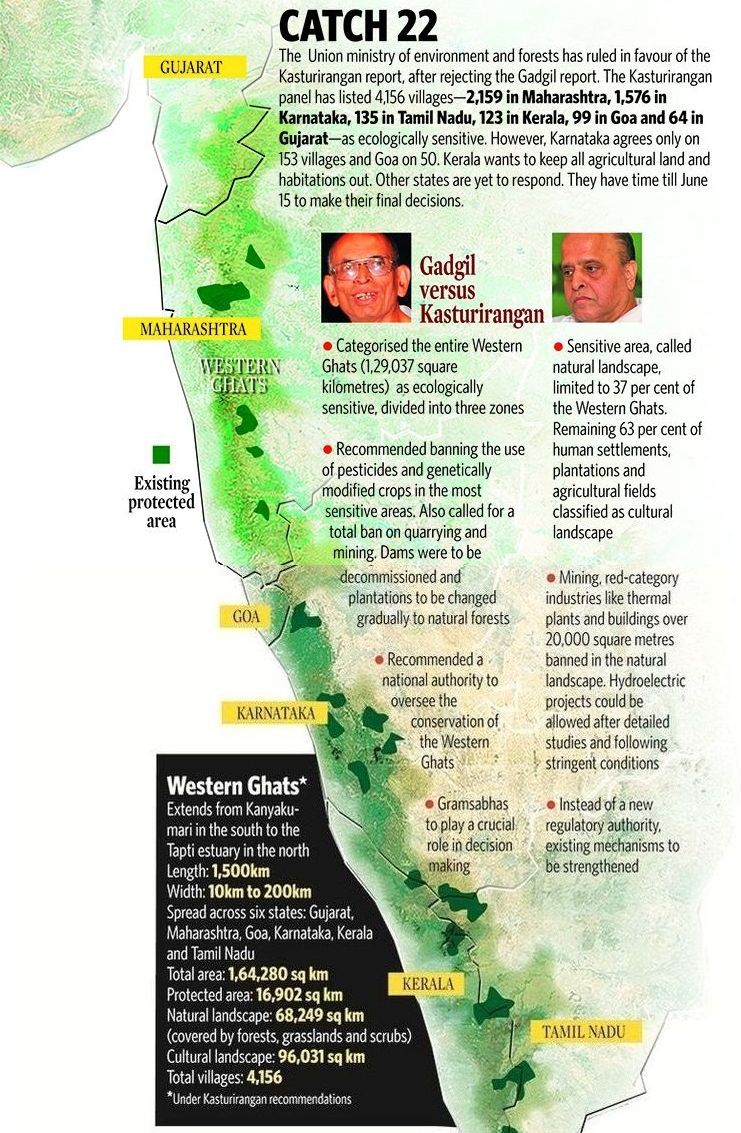

Development versus environment is one of the great debates of our times. The Union ministry of environment and forests (MoEF) is staring at one such challenge, the preservation of the Western Ghats. The six states that share the range―Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu―are bargaining hard to reduce the area under the proposed ecologically sensitive areas (ESAs) in the Western Ghats.

The high level working group headed by space scientist Dr K. Kasturirangan, in its report published in April 2013, declared 4,156 villages―2,159 in Maharashtra, 1,576 in Karnataka, 135 in Tamil Nadu, 123 in Kerala, 99 in Goa and 64 in Gujarat―as ESA villages and the states were asked to carry out a “physical verification” of such villages and file their reports by April 30. The deadline was extended to June 15, as only Kerala, Karnataka and Goa filed the reports. The ministry has now told the states that if they did not respond by June 15, the demarcation in the Kasturirangan report would be deemed as final.

Conservation is no longer a matter of choice, but a compulsion, as evident from calamities like the recent earthquake in Nepal, the Kashmir floods (2014), the landslide and flash floods in Uttarakhand (2013) and the Indian Ocean tsunami (2004). Yet, the government has shown no sense of urgency to implement the expert committee recommendations to safeguard the Western Ghats, which is among the world’s biodiversity hotspots, say environmentalists.

“Denudation, submergence of forest under river valley projects, encroachment of forest land, mining, felling of trees to raise plantation crops, infrastructure projects like roads and railways, soil erosion, landslides, habitat fragmentation and decline of biodiversity from overexploitation of the forest and natural resources continue unabated. We want the government to implement the Gadgil report as it is foolproof and pro-environment,” says Panduranga Hegde, member of the Save Western Ghats Movement.

The Manmohan Singh government had constituted the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel headed by ecologist Madhav Gadgil in 2010, to study the impact of population pressure, climate change and development activities in the Western Ghats. But after the panel submitted its report in August 2011, it was ignored, as states dubbed it as "anti-development".

A year later, in August 2012, the MoEF constituted another high-level working group headed by Kasturirangan to “revisit” the Gadgil report. The Gadgil report had declared the entire Western Ghats region as ecologically sensitive. But the Kasturirangan report demarcated only 37 per cent of the Western Ghats as “natural” landscape, and classified the remaining 63 per cent as “cultural” landscape, which had human settlements and agricultural fields. The natural landscape, comprising 4,156 villages, was declared as “no-development” zone.

The Central and state governments seem to be dragging their feet on the implementation of even the Kasturirangan report. The Karnataka government has agreed to notify only 153 of 1,553 villages proposed in the Kasturirangan report, while Goa feels only 50 of 99 villages fall within eco-sensitive areas. Kerala, which submitted its response a year ago, asked the MoEF to keep agricultural land and habitations out of ESAs.

The Karnataka government in its reply dated April 24, 2015, has mentioned “public outrage” as the reason for dropping more villages from the ESA list. It has also told the Centre that such “antagonism” would only “defeat” the conservation efforts. Local communities, however, allege that the public consultation has been a sham. “It is only a bureaucratic drill, as genuine stakeholders like farmers, tribals, gram panchayat members or citizen groups have had no say. The locals are not polluting the Western Ghats, but the MNC-driven development like tourism, mining and plantations is,” says Vittal Hegde Kalkuli, an environment activist from Chikkamagaluru district of Karnataka.

“If the government wants to conserve forests, it should ensure better livelihood options for the locals. But this does not mean eviction. We oppose the inclusion of our villages as it would impose restrictions, from banning plantations to prohibiting the use of pesticides. We are open to better and green farming practices if we get technical and financial support,” says Vittal Hegde.

Former chairman of the Western Ghats Task Force, A. Ananth Hegde, says the committee has not recommended eviction, but mooted green farming practices. "Sand extraction, mining, mega power plants and industries will be banned if a village is notified as ESA, but water, land and flora and fauna will flourish. ESA villages will get incentives for specific sector development. Vested interests have launched false propaganda about the reports," he says.

The Kasturirangan report is, however, drawing flak from environmentalists for its drastic reduction of the ecologically sensitive zone to around 70,000 square kilometres. Unlike the Gadgil report which warned against ecological distress if hydel power projects were to be taken up at Gundia in Karnataka and Athirappilly in Kerala, the Kasturirangan report said the government should reassess the impact of the projects on ecology and proceed with extreme caution, which amounts to “endorsing” exploitation, allege NGOs.

“No locals have asked for dams or agro-economic zones. This form of development is thrust upon people. Dams ruin the pristine forests and biodiversity and make water an expensive commodity as lift irrigation is power-intensive. The agro-economic zones will kill indigenous crops and forests. Agriculture should be regulated based on water availability and food security needs rather than market considerations," says Ananth Hegde.

C. Yathiraj, an environmental activist from Tumkur, says the Western Ghats affects more than six states as 54 peninsular rivers originate from the range, providing water for nearly 25 crore people. "Sadly, water from irrigation dams is being diverted to quench the thirst of expanding urban spaces and industries. Check dams at hill streams and use of pesticides by tea and coffee plantations are polluting the flow downstream," he says.

Gadgil agrees. In an open letter to Kasturirangan, he writes: "You have advocated one-third of what you term natural landscapes to be safeguarded by guns and guards and two-thirds of so-called cultural landscapes, to be thrown open to development, such as what has spawned the Rs35,000 crore illegal mining scam of Goa. This amounts to attempt to maintain oases of diversity in a desert of ecological devastation.... Ecology teaches us that such fragmentation would lead, sooner, rather than later, to the desert overwhelming the oases."

Interview/ Madhav Gadgil

The Kasturirangan report is a perversion

By Prathima Nandakumar

Only a people’s movement can save the Western Ghats, says Madhav Gadgil, the man who prepared a 500-page report on saving the mountain range. His report was, however, rejected by the government, which set up a panel under K. Kasturirangan to “revisit” it. In an interview with THE WEEK, Gadgil says the Kasturirangan report is a “perversion” and is “anti-constitutional”.

Excerpts:

Are you hurt that your report was sidelined?

I am saddened by the fact that the government made my report a basis for misinformation, instead of taking it as a starting point for conservation efforts. It was prepared with a strong rationale and commitment. Our committee had explicitly mentioned that it was not the final demarcation, but only an initial proposal, which needed to be taken back to the gram sabhas in the Western Ghats, so that people get to decide the ESA [ecologically sensitive area] status of their villages.

What do you think about the Kasturirangan report?

The Kasturirangan report is not a dilution of our report, but a perversion as there is a specific statement that dismisses the role of local communities. It clearly states the locals have no say in the economic decisions. This is anti-constitutional as the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution mandate people's participation in decision making.

Do you believe “public consultations” were held during the resurvey of the ecologically sensitive villages?

Sadly, the resurvey of the villages has been anti-democratic, too, as a few bureaucrats visited the panchayats to collect public opinion. The process of consultation, especially in Maharashtra, has been a sabotage of democratic process. The expert panel reports were not made available to the people in the local languages.

How do you look at the states bargaining to pull out their villages from the ESA category?

I am not surprised that the state governments are opposed to notifying the demarcated villages as ESAs. I am not bothered about the product [the number of villages finally declared as ESAs] as the process [of public consultations] has itself been a sabotage of democracy.

Did you face any opposition from people, while demarcating the ecologically sensitive zones?

I am afraid the government would never talk about it. We have followed a sound methodology to demarcate the ecologically sensitive areas in the Western Ghats and suggested measures for its conservation and development. Our panel received gram sabha resolutions from a cluster of 25 villages in Sindhudurg district [in Maharashtra] as they wanted their areas to be brought under ESAs. We have got similar representations from many gram panchayats. The locals are not opposed to my report. On the contrary, the villagers are opposing illegal stone quarrying and mining and are seeking the ESA tag to put an end to that menace. But the government simply does not want to listen to the genuine stakeholders as they are busy safeguarding the interests of various lobbies.

Your report has been dubbed as "anti-development". Is the Western Ghats overburdened with development projects, perhaps beyond its carrying capacity?

For every project, a proper scientific assessment and feedback from the local communities are a must. The unwillingness of the government to discuss the adverse impact of projects in the Western Ghats is nothing new. There is no study on the carrying capacity in the mountain ranges as governments have been scared that the malpractices and violations in the region would stand exposed.

In 1995, when I was with the Indian Institute of Science, the H.D. Deve Gowda government in Karnataka approached me to conduct a carrying capacity study in the Dakshina Kannada region. In 2010, [Union environment minister] Jairam Ramesh asked me to carry out a similar study of coastal Maharashtra to outline its carrying capacity. But both these studies were scrapped in the initial stages itself.

Are you still hopeful that the Western Ghats will see the right kind of intervention?

Prime Minister Narendra Modi on his first day in office said development was a people's movement. Our report is on the same premise. If Modi is serious about what he said, he will take up the issue of Western Ghats protection, too.