By the time Amit V. Masurkar’s Newton reached theatres, on September 22, critics had warmed up to it. The film, a satirical take on Indian democracy, was made on a shoestring (Rs 9 crore) and had a hard-hitting theme. On the same day, the Film Federation of India announced that Newton would be India’s official entry in the Best Foreign Language Film category at the 2018 Academy Awards.

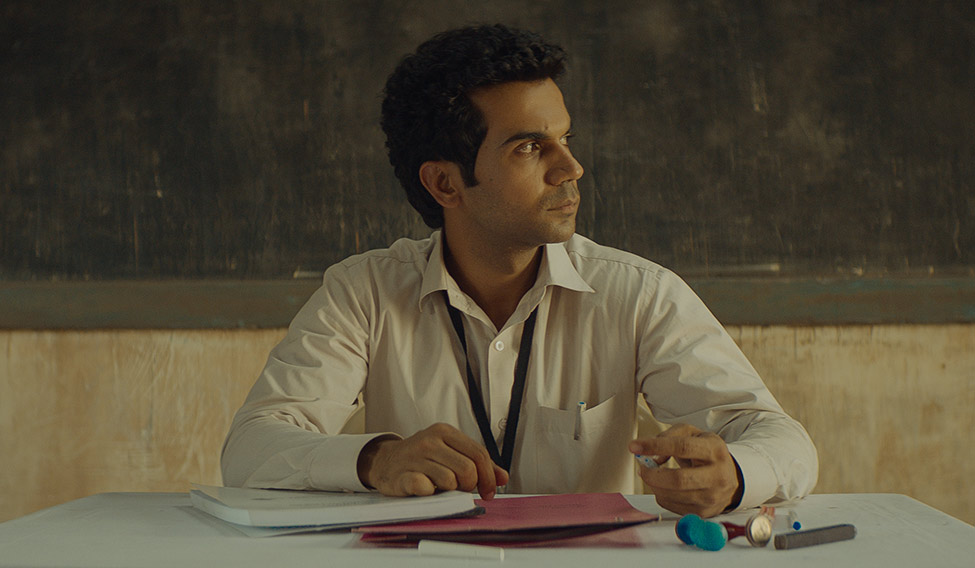

A day later, reports alleged that the film was a rip-off of the 2002 Iranian film Secret Ballot. Social media went berserk and a few critics pulled down their positive reviews. Starring Rajkummar Rao as the titular character and Pankaj Tripathi as a Central Reserve Police Force officer, Newton is a dark comedy about a rookie government clerk who is entrusted with conducting elections in the Maoist-dominated jungles of Chhattisgarh.

Secret Ballot is about a female election agent and a gun-toting soldier who try to get people living on an island to vote. Filmmaker Anurag Kashyap, who has been vocal in his support of Newton, posted on Facebook, screenshots of an exchange with the producer of Secret Ballot, who had watched the Indian film and called it a “pretty decent film, definitely no rip-off of our Secret Ballot (even if the general concept is the same)”.

The allegations left the film’s producer, Manish Mundra, overwhelmed, but he is pleased with the backing from the industry. “We are now gearing up for our US distribution campaign and we will give it our all to bring the Oscar to India,” he said.

THE WEEK met Masurkar, Newton’s director, at the office of one of the film’s presenters, Aanand L. Rai, on the day of its release. It seemed surreal to him that his film was going to the Oscars. He was in Rai’s office to introduce journalist and Adivasi activist Mangal Kunjam, who hails from Dalli Rajhara area, where Newton was shot. Kunjam’s knowledge of the place came in handy for Masurkar. He has often been caught in the crossfire of the battle between Maoists and CRPF personnel—a conflict that is depicted in Newton.

“Every point of view is important,” said Masurkar, who had not expected Newton to become a runaway hit. “CRPF constables in that area belong to low-income families, with very little awareness of human rights and [having had] no psychological counselling. They feel victimised by human rights activists and the press.”

The director was inspired by how India conducts elections in every nook and cranny of the country. “We met academics, journalists, election commission officials, CRPF personnel, surrendered Maoists, lawyers and ordinary voters. This film is enriched by their experiences,” he said. Masurkar suggested that the film be shown to people of Dalli Rajhara and other areas.

Rahul Kadbet, head of programming, Carnival Cinemas, expressed his surprise at how demand for the film skyrocketed after a weak opening. Except for the first shows, he said, almost all subsequent shows had 95 per cent occupancy.

“We realised, in our writing process, that many films, not just Newton, are based on Newton’s laws of motion,” said Masurkar, referring to a scene in the film where the protagonist says “ye mere action ka reaction hai”. “The first act is inertia, the second act is momentum, and the third is an equal and opposite reaction.”