A closeup of a finely crafted piece of foot jewellery worn by a Hindu bride, a view of road-making between Colombo and Kandy, a portrait shot of a young Tamil girl perched atop a chair, two women estate workers plucking tea, an old map showing boundaries with India, an annual Buddhist procession, a group of Sinhalese devil dancers... these evocative photographs are part of a new exhibition that opened at the National Museum in Delhi on September 26.

Titled Imaging The Isle Across: Vintage Photography from Ceylon, this seminal work comes from the Alkazi Collection of Photography, commemorating 90 years of art collector and theatre doyen Ebrahim Alkazi. It has been put together by his 35-year-old grandson, Rahaab Allana, who is the curator for the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.

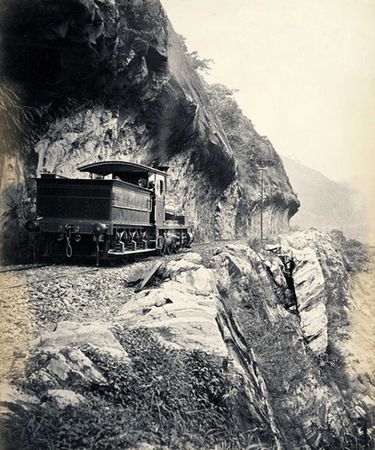

A railway engine on the Colombo-Kandy railway track in the 1870s.

A railway engine on the Colombo-Kandy railway track in the 1870s.

This is, in all probability, the first time that life as it was in Sri Lanka in the 19th century will be available to Indian viewers. This initiative is considered to be a tribute to the varied histories of the isle across us, reframing India’s relationship through these surviving visual archives.

The exhibition also features the work of two prominent Sri Lankans, Lionel Wendt, a pianist, photographer, critic, and cinematographer, and Anoli Perera, a contemporary artist, accompanied by screenings of some of the first documentaries on the life and people of Ceylon. It will be on till November 10. Excerpts from an interview with Rahaab Allana:

How did the idea for the exhibition come about? How did you go about curating it?

Photography in south Asia is attempted dialectically in this exhibition with a reference to one region: Ceylon. As the visual culture of the colonial period remains a challenging, exploratory domain in today’s media-dominated world, the interrelations between the archives of the subcontinent may not readily strike the reader or viewer as collegial or drawn from a networked past. The 19th century presents an early encounter with the colonial environment, dominated by cultural change and travel as the state transformed into a modern entity through infrastructure and political expansion. The paradox of how the city developed and opened up to a global economy is bolstered by an imperial vision, an uncompromising worldview with regard to people from the subjugated nations, often leading to harsh and clinical preconceptions about a country’s resident population.

Within this exhibition, some attention has been paid to certain segregations that seem logical within the context of a photography archive—colonial buildings and cityscapes established in the 19th century, portraiture in the studio, landscape views and the urbanscape that captures the imagination of those drawn to it. However, through these frames, we also prominently foreground its people, the labour, economy, the religion and a growing urban class, which transforms the city into a cosmopolitan entity that negotiates hierarchies. The exhibition, therefore, begins with landscape images, as an entry into the region being explored for the first time through the camera. As the lens roams and settles upon its subjects—from the coast further inwards—the world seems to enlarge capturing not a tribal population, but one close to the rhythms and sways of the sea and sand with refined sartorial conventions and religious ceremonies.

Which are some of your favourite picks from the exhibition?

The image of the Rodiya boy is an interesting portrait as it manages to subvert a clinical approach to a subject. The boy seems to have captured the imagination of the photographer, enabling an intimate reading of his character. On the other hand, an image by Lionel Wendt of a labourer that is juxtaposed with the lethargy of country life of the colonials brings to the fore a kind of contrast necessary in the perception of 19th century, if not today: a representation of conflict and elite lifestyle.

A boathouse on the Kelani Ganga river in the 1880s.

A boathouse on the Kelani Ganga river in the 1880s.

How would you contextualise present-day India-Sri Lanka relations and the timing of this exhibition?

The question is really about a respect of regional diversity rather than imposing cultural specificities. Sri Lanka has shared migratory labour with south India, and the reverse, too, has occurred. But differences in language, shifts in religious leanings make us aware that it is through pre-independence archives that the postcolonial be understood or approached. Sri Lanka has had its civil war that ended only recently and hence it still grapples with that modern history, edging its way into contemporary culture. The point is to understand how south Asia also has a unique identity, and political differences should not be the only terms of engagement, but rather a cultural inclusion of each other's customs and ways. This continues to engender a composite culture, one that we continue to articulate.

Early life in Sri Lanka... what parallels do you see with India?

One can easily talk about Buddhism from a religious point of view, or Christianity, as Ceylon was a colony of the Dutch, Danish, Portuguese, French and then the British. This is what gets represented through photography, if not the development of the railways and the infrastructure of the country. Though wars create a disjuncture, the cities of Colombo and Kandy today stand as thriving coastal towns, replete with modern architecture, art centres, as well as an art biennale, which heralds all forms of interdisciplinary dialogue around the role of the practitioner and the institution. And in this, photography maintains a significant presence seeking to address how documents of the past propel new media exchanges in the present.

The Lionel Wendt Art Centre in Colombo, for instance, is one such outgrowth of a heady modernism, connected even to Santiniketan through Harold Peiris, painter and secretary of the 43 Group, who settled there for two years, a time when both regions—Sri Lanka and India— stood on the precipice of independence as one nation. The connection through Ananda Coomaraswamy [Ceylonese historian and philosopher of Indian art] is also important.

The work also marks 90 years of Ebrahim Alkazi's work. What does he say about this exhibition?

Alkazi always saw photography in the context of the interplay of reality, time and tradition. To surmise, I would say that he considers this a step towards more collaborations, both institutional and artistic in the future.