On June 3, 1947, Lord Mountbatten announced his government’s decision to divide British India into two successor states—India and Pakistan. A day before, on June 2—which happened to be a Monday—he had visited Mahatma Gandhi, who was dead against the idea of partition.

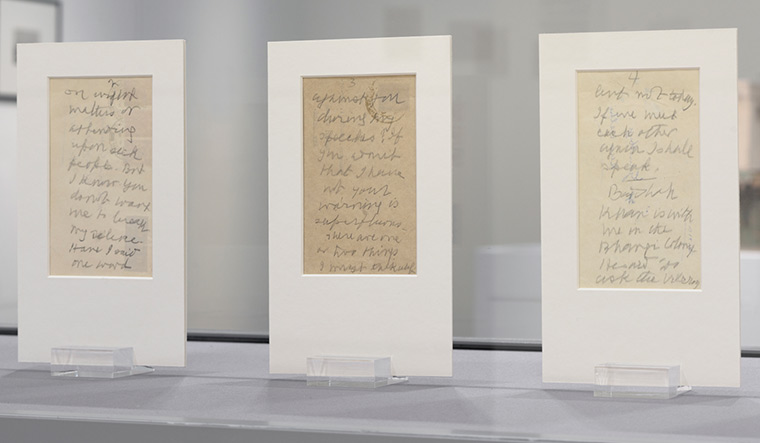

Gandhi had vowed to observe silence every Monday, and he was adamant about it. So, he communicated with Mountbatten by writing notes on the back of used envelopes. A collection of five such envelopes—the only remaining record of the historical exchange—is the “centre-piece” of ‘Tangled Hierarchy’, a show curated by acclaimed Indian artist and curator Jitish Kallat. The show opened on June 2—on the 75th anniversary of the momentous exchange—and will continue till June 10 at the John Hansard Gallery at the University of Southampton.

“When he took his vow of a weekly day of silence, Gandhi had reserved the right to speak on two occasions,” says Kallat. “…about speaking to high functionaries on urgent matters or attending upon sick people. But he wrote [on one of the envelopes] to Mountbatten: ‘I know you don’t want me to break my silence’. Gandhi was letting Mountbatten know that his silence was loaded, his disapproval of partition was known in the public domain and he was aware that the latter would prefer silence.”

Bringing the “Gandhi envelopes” to the centre of the conversation was important, according to the curator. “They are, of course, reflecting back to that historical moment, then unfolded as the tragedy of partition—and the violence and the bloodshed that followed in the weeks after that. But they are also setting up relationships between silence and speech, and between bodies and borders,” he says.

The exhibition intelligently combines archival and scientific artefacts, alongside works by contemporary artists. One among these artefacts is a “mirror box”—a therapeutic box invented by Indian-American neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran to treat post-amputation patients experiencing “phantom limb pain”. “Phantom pain (a pain lingering in a body part that is no longer present) is a running trope in the exhibition,” says Kallat. “On one side, you have this ‘Mirror Box’ by the neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran, and British artist Alexa Wright’s ‘After Image’ series which documents amputees along with stories of their phantom pain, and on the other side is essentially a photograph by Homai Vyarawalla, India’s first female photojournalist, who documented the ratification of partition at the Indian National Congress. The picture shows several of its members raising their hands in acceptance. Those hands have another dimension of meaning when it is read alongside these images of amputation and pain. There is a hidden prompt to see the amputation of the body along with the amputation of the land.”

The curator says that the pain and struggle related to displacement—especially as a result of partition—is another underlying theme of the exhibition. It is examined by Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum’s installations and late Indian-American artist Zarina’s work, ‘Atlas of My World’. Precariously suspended glass material that, when combined, forms a map of the world is one of the installations by Hatoum. In another work, a cut-up map could be seen mutating into a bag. This installation is exhibited along with two refugee luggage trunks from the partition era. The archival material was loaned from the Partition Museum in Amritsar. Zarina’s ‘Atlas of My World’ includes prints that show tense borders across the world. “Zarina is a child of partition; her family moved at the time of partition,” says Kallat. “[Her work] comes from that history.”

American artist Paul Pfeiffer’s digital video loop, ‘Caryatid’, features footage of football players repeatedly falling onto the pitch. “These are real footage from a match. But you would find that something is odd with the video,” says Kallat. “You would realise that it is the moment of a foul; the person who is colliding against the falling person has been erased from the screen. Normally, a foul happens when someone is about to reach a goal. You would find that the players are always falling near a line, which is also a kind of border on a football field. A game is nothing but a metaphor for the world.”

Kallat adds that these falling figures get a different dimension or meaning when someone sees them alongside ‘Games in a Refugee Camp at Kurukshetra’—a Henry Cartier-Bresson photograph at the exhibition. The 1947 black-and-white photograph documents a group of men playing at a camp post-partition. “The photograph shows a light moment at a very tense refugee camp,” says Kallat. “Everyone in the picture looks like they are falling. In a way, Paul Pfeiffer’s recent video talks to this historic photograph.”

The exhibition also captures how history repeats itself, especially in the context of war and violence. It is best reflected in Ukrainian artist Mykola Ridnyi’s video work, ‘Seacoast’. Filmed on the Black Sea coast, the video shows a static horizon dotted with figures of fishermen, with jellyfish periodically splattering onto the ground, bracketed by the sound of warplanes and bombs. Ridnyi created this video as a response to the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008.

“It is almost like a replaying that happens today [with Russia invading Ukraine],” says Kallat. “And, it is almost like a causal loop—a circular chain of variables affecting one another in turn—that comes back.”

The curator adds that the idea of causal loops or the cyclical nature of history echoes throughout ‘Tangled Hierarchy’. “While I was finalising details of the project, I realised that the human displacement that is happening now during the Ukrainian crisis mirrors the human displacement during the Indian partition,” he says. “It again comes back to this question of the eternal return of human tragedy or human folly or human aggression.”