It had all the elements of a thriller—spies, a honeytrap, politics and foreign intelligence agencies. It was a case that forced a heavyweight chief minister to resign, thereby reshaping Kerala’s political landscape. The accused included top scientists of the Indian Space Research Organisation, who were handpicked by none other than Vikram Sarabhai, and two Maldivian women, allegedly working for Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence.

Investigations were carried out by the Kerala Police, the Intelligence Bureau and the Central Bureau of Investigation. The end results of this tumultuous case were a change in leadership in Kerala, the ruined careers of two scientists and a long delay in the ISRO’s cryogenic development programme. Subsequently, the ISRO espionage case also resulted in a couple of books.

The latest one is by Siby Mathews, the main investigating officer of the case. His book Nirbhayam (Fearless), chronicles his career, and a significant part is dedicated to the case. It talks about the tug of war between various investigating agencies, misuse of political establishments, loopholes within the system, political conspiracies and the alleged involvement of a former prime minister’s son.

Mathews also paints the agony he had to undergo during the time of investigation, and even after the case was closed. “I am the victim of the ISRO case,’’ he said.

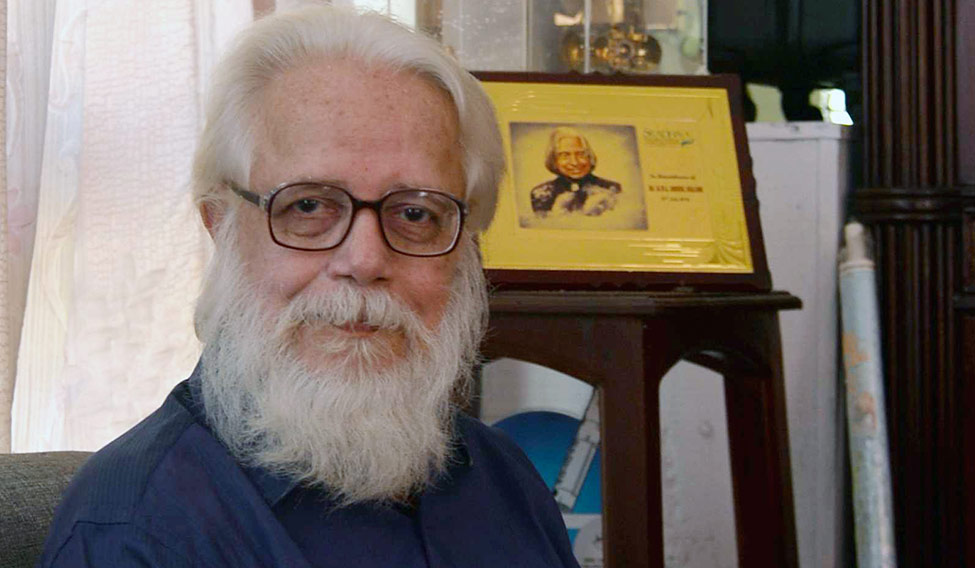

Mathews has every reason to worry as a case seeking disciplinary action against him for fabricating evidence is in front of the Supreme Court. The verdict is expected in August. The case was filed by the main accused in the ISRO case, S. Nambi Narayanan—once known as “junior Kalam”—who was the brain behind the design of the systems used in Chandrayaan, Mangalyaan and PSLV.

It all started in October 1994 with the arrest of a Maldivian woman, Mariam Rasheeda, from a hotel in Thiruvananthapuram for overstaying her visa. The police also confiscated a diary from her room, which had jottings in Dhivehi, the national language of Maldives. When the contents of the diary were translated into English, the case took a dramatic turn. The diary had the names of two senior ISRO scientists—Narayanan and D. Sasikumaran—who were working on the space agency’s ambitious cryogenic development project. It also named a “Brigadier Srivastava” (this name was linked to inspector general of police (south zone), Raman Srivastava). After questioning Rasheeda, another Maldivian woman, Fauzia Hassan, was also arrested.

Siby Mathews

Siby Mathews

Rumours spread that the two women were spying for the ISI and that they had honeytrapped the two scientists and elicited secret information on cryogenic technology. The state government—under CM K. Karunakaran—formed a special investigation team led by Mathews.

Several arrests were made including that of the ISRO scientists. Mean-while, Srivastava, Karunakaran’s man Friday, being linked to the case put the CM under the scanner. The rival ‘A’ faction in the Congress made good use of the spy theory and Srivastava’s alleged involvement to push for Karunakaran’s resignation (he was replaced as CM by A.K. Antony, leader of the rival faction).

The case was later handed over to the CBI. The CBI, however, rejected all evidence submitted by the state police and IB. According to Mathews’s book, the CBI took this U-turn after the name of Prabhakar Rao, the son of the then PM P.V. Narasimha Rao, came up in the case. (Former IB joint director Maloy Krishna Dhar, in his book Open Secrets: India’s Intelligence Unveiled, has mentioned this turn of events.)

Two years later, in 1996, the CBI cleared all the accused and also filed a closure report before the court. Later, the SC upheld the CBI investigation which concluded that the so-called sex scandal was fabricated by police officers, including Mathews.

But, by then, several careers were ruined and lives were torn apart. Though Narayanan retained his post at ISRO, he was taken out of the cryogenics department—which he was heading before the case—and transferred to Bengaluru, which he said curtailed his career growth. Narayanan decided to fight and filed a case seeking action against the officers responsible and a compensation of Rs 10 lakh.

“I lost everything; my career, my family life, my future... but still I wanted justice,’’ Narayanan told THE WEEK. “I have no regrets in having wasted my life in courtrooms. I am fighting this case so that no other Indian will be persecuted like this according to the whims and fancies of investigating officers.’’

Sasikumaran, however, deemed it better to let bygones be bygones. He said: “My life and career were already ruined. I didn’t want to waste the rest of my life, too, like Nambi, who is spending his life in courtrooms.’’

The case was so hyped up that everyone associated with ISRO were deemed potential spies. There were instances of ISRO vehicles being pelted with stones and auto-rickshaws and cabs refusing to ply for ISRO staffers. A former ISRO scientist who requested anonymity, said: “The ISRO lost its organic growth after the case. Everything became so sarkari after that.’’

All scientists THE WEEK talked to insisted that the ISRO case would not have happened if the police officials had minimum knowledge about rocket technology. “They should know that rocket technology is not something which can be sold in a few drawings and papers,’’ said Narayanan.

This is something which was corroborated by scientist E.V.S. Namboothiri, who was questioned by the CBI in connection with the case. “Rocket science is very complicated,” he said. “Finer details are only available with the departments concerned and no department has complete details. Even if somebody managed to get a bit of information, it will be of no use,’’ he said.

According to Mathews’s book, Namboothiri had shared crucial information which could have proved that the ISRO spy case was real. Namboothiri, however, denied having shared any secrets with Mathews. “I was aware of no secrets and I shared none,’’ he said.

However, Namboothiri’s argument that no harm could be done by sharing little details is strongly refuted by R.B. Sreekumar, who was deputy director of the IB at Thiruvananthapuram during the investigation. “Even a small bit of information is crucial when it comes to space science. If you develop some unique technology and report it to your boss as per the system, your boss will win the Bhatnagar award. But if you sell it outside, you can earn crores,’’ said Sreekumar, who later became Gujarat’s director general of police and is best known for his stand against the government after the violence in the state in 2002. He added that North Korea and Pakistan were closely monitoring ISRO at that time. Sreekumar strongly believes that espionage did happen and that Rasheeda was spying for Pakistan.

T.P. Senkumar, who was appointed by the Left government that came to power in 1996 to reopen the case, also insists that the CBI did not conduct a proper investigation. “I can prove it,” he said. Senkumar insists that he was the true victim of the case as it earned him the wrath of many, including Srivastava, even though the case was thrust upon him. “I tried to convince the government that it was not prudent to reopen a case closed before the SC. But I was forced to take it up. Eventually, I was the one who suffered. It affected both my personal life and my career,” he said.He says there is still a lot of mystery surrounding the ISRO case. “Why these top scientists were in touch with the Maldivian women who had a background of espionage is yet to be found,” he said.

Mathews, too, echoes these thoughts. “Mariam Rasheeda was a spy with a Pakistan connection, no doubt. What she took from ISRO is immaterial. The fact that this spy had close relations with two top scientists working in an ambitious ISRO project is proof enough,’’ he said. “Unfortunately, we could not establish it due to various reasons.” Mathews added that the truth will come out one day.

The truth is exactly what Narayanan also wants. “Who was behind the ISRO spy case and who benefited. It is important to find out the motive behind the case. If you find that, then you know who the real spy was,’’ he said. According to him, India was pushed back at least 15 years in the cryogenic programme because of the case. “We could have been a world leader in this [cryogenic rocket engines] if the ISRO case had not happened,’’ he said. Narayanan wants a joint investigation by the R&AW, the IB and the CBI to find the “real culprits’’.

There seems to be more to the ISRO case than what has been revealed. Sasikumaran suspects the US Central Intelligence Agency had a hand in the whole conspiracy. “It is important to know why this case was fabricated and who was behind blowing the case out of proportion. I am sure that some larger interests are behind the whole thing,’’ he said. He suspects that the CIA must have influenced the IB. (In 1992, India had signed an agreement with Russia for transfer of technology to develop cryogenic fuels. Then US president George H.W. Bush wrote to Russia objecting to this agreement. Hence the theory of CIA sabotage.)

After Mathews’s book, now it is Narayanan’s turn. He is coming out with two books—one in English and another in Malayalam. The English version, expected to be released in July, is being published by Bloomsbury. An international production house is also planning a feature film based on Narayanan’s life.

What makes the case still interesting is the fact that almost everyone involved in it, from the first investigating officer (Mathews) to the last one (Senkumar) and the accused, claim they are the victims. They all say that the ISRO spy case ruined their lives.

Former CM V.S. Achuthanandan, perhaps, had the last word on the case. While releasing Mathews’s book, he said: “Nobody knows whether the ISRO case that rocked the state in the 1990s was a truth or a myth.’’