Akanksha Sharma was recently in Singapore, creating an induction programme for marine professionals. From the perspective of her age, 27, "they were all old people, in their late 30s and even 40s; marine engineers, captains and vice presidents, those types," she recounts. The group was naturally stunned to see this chit of a girl coming over to create workshops for them, and looked askance at her skills. However, it was not long before the "oldies" realised that Sharma was more than adept at her work. Grudgingly, they began treating her with respect. The encounter neither offended nor amused Sharma. It was just about the regular experience she faces when out of India. "Whether in Europe or the US, I deal with the 35-plus age group, and, mostly, people are over 45. It is only in India that I encounter more 30-somethings in my workspace," she says.

One of the youngest instructional designers for corporate training certified by the US-based Association of Training and Development, Sharma may be the little girl in her field, but her experience is not too different from that of Rwitwika Bhattacharya, the founder of Swaniti, an organisation that does consultancies with parliamentarians. "In India, I see younger people everywhere, but when I am dealing with officials at the United Nations or even New York, I am immediately with much, much older people," she says. At 28, Bhattacharya leads a team of enthusiastic professionals, many of whom, like her, have left hefty dollar pay packages to work in the developmental sector in India. The average age of her employees is, not surprisingly, 27.

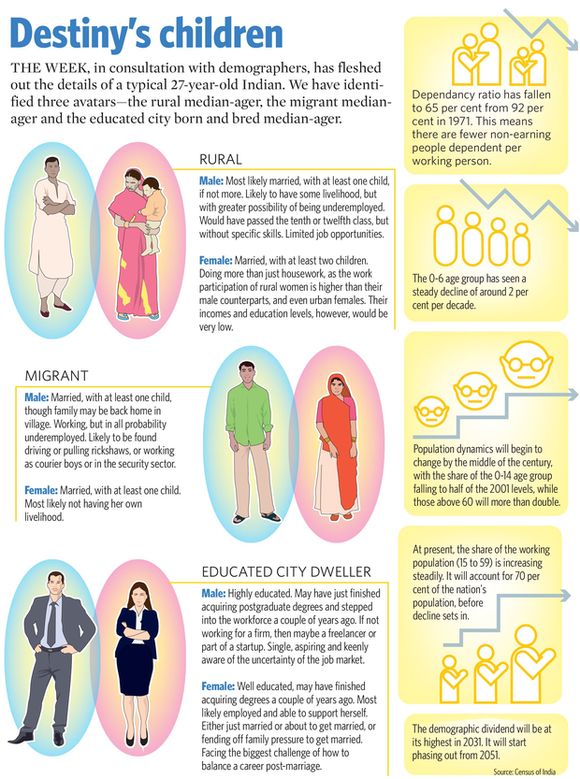

Meet India's median-agers, the 27-year-olds who are going to be the driving force behind India's economy, development and ambitions over the next decades. It is from these young men and women that the country hopes to reap the dividends of its human capital. Age may just be a number, but when that number is 27, it assumes a whole new dimension.

India, with half its population below 27, has stepped into what demographers call its "window of demographic opportunity", where over 60 per cent of the population is in the working age. It's the time when the youth, by the sheer strength of its numbers, will make its presence felt in every sphere of activity.

Their dreams for the country will drive the India growth story. Being young in India was never so exciting, and at the same time, never more challenging. India’s youthful face is in sharp contrast to an ageing workforce across the developed world. The median age is 46.1 in Japan and Germany, 37.6 in the US and around 40 in France and the UK. Even China’s visage is wrinkling, its median age having gone up to 36.7.

"Yes, it's a great time to be young in India, because there is a new energy here," says ace wrestler Geeta Phogat, who hails from Bhiwani, Haryana, where many girls are either killed at birth or, if spared, treated worse than animals. The 27-year-old is training at a camp in Lucknow. "Imagine, here I am, with three of my sisters, working towards our dream of Olympic gold. This is new India, a place where dreams can come true. In another age, we would all have been married off long ago," she says. India's median-agers are products of a liberalised economy. They have grown up seeing multinational brands stocking retail shelves. They have had the element of choice, whether in brand selection (an older generation remembers a past not too far back when Bata and Tata took care of almost all daily needs), television viewing and more significantly, career options. They have seen the economy booming, with their seniors earning giddy salaries. They are mostly products of nuclear families with most having either one or even both parents still in their jobs. All of which means that right now, they have fewer responsibilities and thus can afford to both splurge on, and invest for, themselves. Bengaluru-based software engineer Anay Kishore has just bought his first car, a Honda Brio, while Sharma has booked a roomy apartment in Greater Noida.

On the flip side, though, they have also grown up seeing pink slips and had first-hand experience of not getting admissions for courses of their choice despite near perfect scores. "Our parents may have earned less, but they didn't face the job insecurities that our generation deals with," says Bollywood actor Richa Chaddha, a 27-year-old.

It is not surprising then that this is a generation where sunshine optimism and crushing disenchantment co-exist. But don't let that, even for a moment, lead you to believe that these youngsters are afflicted with bipolar disorder. The conditions that have shaped this generation have only made it a very grounded one. These are the folks who, when riding the wave of India's growth story, are keenly aware that they are fortunate and that it doesn't take much for the tide to turn. As Kanika Nayar, a consultant with Ernst & Young, says, "I know I am of the privileged minority who got the right education and the job I wanted and that I am able to do what I want in life. Our youth force, however, is not dominated by people like me."

Those not riding the crest know equally well that there is opportunity at the turn, one just has to seek it out. And when opportunity doesn't come knocking, they know they can jolly well create it. "I completed my postgraduation in 2010, in the midst of a recession. I was lucky to get a placement, but others around me had to fend for themselves," says Dinsa Sachan, a freelance science writer who has just returned from participating in a debate on the Asian space race at a science meet in South Korea. She lives by herself in Delhi, her parents are in Kanpur and she has not appealed to them for money since the day she turned 23. "When you have to start out in life as self-employed, you are likely to be better able to deal with uncertain situations," is her philosophy. Calling herself a child of recession, she realised early on that her niche was not in a formal workspace, but being her own boss. Operating out of a collaborative workspace, she sees startup entrepreneurs all around her. "They are the new MBAs," she says.

Dipanshu Dang, too, likes to live by his wits rather than work in a formal sphere. The mechanical engineer from Chandigarh modifies and restores vintage cars, makes corporate films and works as a consultant for college students who design science projects for international competitions. "We live in an age when you have to learn to think out of the box. If you go seeking careers in regular workspaces, you are bound to face competition, become part of the rat race and grow only as much as the firm allows you to," he says.

The urban-rural divide still cleaves this generation into distinct identities, but the exposure to the outside world, through the internet and mobile telephony, has helped forge similar aspirations, something which wasn't visible a generation ago. "We see this so often during interactions in far-flung rural areas," says Utkarsha Bharadwaj of Swaniti. "Jugaad used to be a derisive term once; it no longer is. It is regarded as indigenous technology. One just needs to see the innovations in the rural belts, like the clay refrigerator, all by the youth, to understand that we are a generation that is striving hard to better our lot." Indeed, the right venture capital and government patronage could actually help stem the migration for livelihood to cities, he believes.

Hitesh Kumar comes from a humble family in Amalapuram, a small town in Andhra Pradesh. Wanting to become a doctor, he searched the internet and saw it was cheaper to get his MBBS degree from China. Now working in Delhi, and hoping to do postgraduate studies in paediatric medicine, he says, "Small-town aspirations are the same as those in big cities; I have seen both. We are global citizens, living in an internet age. One just has to strive a little harder when in a small town."

There are certain distinct attitudes among the median-agers which come across in their behaviour and approach. One sees it in the comfort with which they carry their Indian identities and the keenness to discover their desi side, which previous generations tried to brush away as they rose in esteem and career.

Cinema, the best mirror of society, reflects this attitude beautifully, and often, through its own median-agers. Take Kangana Ranaut’s (28) character confidently crooning an English number with a Haryanvi accent in the recent hit, Tanu Weds Manu Returns. Indeed, the success of films that move away from urban Mumbai settings to idiosyncratic small towns is itself very telling.

The more globally connected the generation, the more its confidence in its vernacular. Off screen, too, the icons of this generation show courage to steer away from hypocrisy and come across as honest (even though cynics may say this is a publicity stunt). Ranaut recently turned down an endorsement for a fairness cream while Deepika Padukone (29) opened up about her depression. Anushka Sharma and Virat Kohli, both 27, have handled all the flak thrown at their relationship with an élan that belies their years, and in Kohli’s case, his natural aggression.

Sports stars are typically young, but it is no coincidence that the average age of the Men in Blue who went for the cricket World Cup was 27.3. The swagger that these boys bring to the pitch is again so typical of millennial India’s youth―a touch of arrogance, a bit of rusticity, small-town aspirations and the great Indian dream. Apart from Kohli who flies into unrestrained aggression, most of the others are surprisingly level-headed and cool for their age.

India’s educated 27-year-olds are more likely to be unmarried, even in the smaller towns, as they forge careers and carve personal identities. In the case of women, this is the time when subtle hints for marriage start getting a little louder. But unlike their seniors, for whom career meant pushing back marriage and then dealing with the horror of a crazily ticking biological clock, the women today have a more balanced approach. Given that this generation tries steering away from the rat race, it’s obvious that they are more in sync with the work-life balance philosophy. Anyway, for most women, marriage is no longer synonymous with 'being taken care of' or 'financial security'. "I look for compatibility, intelligence and a liberal attitude in my partner. Financially, I want to be able to take care of myself, always,’’ says Sachan.

Dinsa Sachan | Sanjay Ahlawat

Dinsa Sachan | Sanjay Ahlawat

Using cinematic reference again, the lead character in Piku is a median-ager who takes care of her hypochondriac father. While this affects her relationship meter with other males, she is clear that marriage will be on her terms, and has to take into account her familial responsibilities. As for sex, well, she isn’t a virgin.

That’s your typical median-ager, emancipated yet responsible. There is also a refreshing approach to patriotism in this generation, one that has scents of pragmatism and possibilities and is not overwhelmed by dollops of gooey jingoism. They have caught up with the infectious enthusiasm of the Modi-led energy of jigging up India, but are smart enough to know of the pitfalls ahead. Most dream of India emerging as an economic superpower rather than a subcontinental big brother.

"This Make in India and Skill India are all fine, but why should we limit ourselves to back-office operations and service providing? Why can't we create an India where not just Indians, but even foreigners aspire to settle down because it's the land of opportunity?" says Kishore. Agrees Bhattacharya, "I think the biggest thing pulling us down is ourselves. We have to scale up our ambition, the country should expect more from its median-agers than just basic employability. South Korea rocketed into the big league when it aspired that its next generation would not be workers, but doctors and engineers. We need that, too."

The frustrations their elders had with governance, bureaucracy and politics are still there. There are those like Nayar and Chaddha, who question what future the country is heading into when there is still so much want and disparity. But many believe that rather than burying their heads in the sand, they need to proactively join the system to change it.

While India has always had youth movements, their involvement during recent national and state elections was on a new scale of enthusiasm. The numbers are telling. At last year's parliamentary elections, there were 12 crore first-time voters, making up 10 per cent of the electorate. There are 12 under-30 MPs in this Lok Sabha, double the number in the previous one. Add to that 48 MPs between 31 and 40, and we have a refreshingly young parliament. "India has to work through us; we are not just the present, but the immediate future, too," points out Heena Gavit, 27, first-time MP from Nandurbar, Maharashtra. "Having said that, we, too, have to be more participatory in government. We are a generation that has a different approach, we seek technological solutions. To bring about our way of working, we need to build up our critical mass in every office and sector."

The "oldies", too, realise that they need to tailor policies and schemes for, and along with, the median-agers. Viveka Ranjisinh of Swaniti, who left a corporate career with Deloitte in the US to work in the development space in India, was taken aback when dealing with a Congress MP from Maharashtra. "He told us clearly that as one of the 44 Congress MPs against Modi, he needed to ensure his work would ensure his re-election. He told us to focus on students, as they were the vote bank which would emerge next time, and he needed to woo them. I was initially shocked at the approach, but later realised that development has to be in sync with political agenda.’’

The ministry of water resources, river development and Ganga rejuvenation is planning to send delegates to Germany, Australia and Israel to study their success in river clean-up and water management. Uma Bharti, the minister, is clear that these delegations will have "no seniors, no grey hairs, but will comprise umang aur furti se bhare [spirited and vivacious] very young officers. I have noticed that the youngsters are enthusiastic, they think out of the box. Seniors are more comfortable with status quo, they don’t like change. So when you want change, you know who you have to go to.’’ These, after all, are the people who will not just kickstart resurgent India, but will be its caretakers for at least the next few decades.

YOUNG BLOOD

We should take the lead in governance

By Heena Gavit

Heena Gavit | Amey Mansabdar

Heena Gavit | Amey Mansabdar

I went to school in Nandurbar, a remote and undeveloped area of Maharashtra. When I moved to Mumbai for my MBBS, classmates would ask me where Nandurbar was and I would try telling them exactly where by using landmarks they would recognise.

Even today, there is such disparity between the two places and this definitely affects the way their youth dream. In Mumbai, most of my friends are still unmarried, busy chasing their dreams.

Back home, there is only a polytechnic, so the girls have to go out of town to study further. Not all families allow it, and thus, the dream is snuffed out early. But those girls now tell me that they would like to participate in any project or programme I initiate in Nandurbar.

Our generation is tech-savvy and is definitely more empowered than our parents. But unless regional disparities are addressed, our growth will be lopsided. I would like to create an identity for places like Nandurbar. One day, someone should use Nandurbar as a landmark to guide someone across Maharashtra.

Apart from the select fortunate ones, our youth is still largely educated and unemployed, or underemployed. Prime Minister Modi has shared his vision of Make in India, which will certainly bring jobs to smaller towns. But we have to think big ourselves, too. If so many top firms in the US and the UK have CEOs who are Indian and were educated in India, then it certainly means we are capable. Why not create such opportunities of growth in India? The government and private sector should work on creating these opportunities.

Our generation has to take the lead in every field, and that includes governance. The youth is cynical of political participation, but unless educated young men and women join the process, how will we bring about any change?

Gavit is a BJP member of the Lok Sabha.