Alka Verma lives in constant fear of disease and death. No, Verma is not over the hill, she is just 39. Yet, she keeps fretting about how her two children and husband would get by if something happened to her. So, she does all that she can to keep herself in fine fettle.

She follows a strict diet and exercise regimen, stays away from everything that may be harmful to her health. And, to rule out even the minutest possibility of any disease in her body, she undergoes a thorough medical checkup, which includes simple and complex blood tests, urine test, mammography, pap smear, and a few other tests, once in three months.

“On my maternal family side, high blood pressure, which is a silent killer, is common and I don't want it to affect my family,” says Verma, who reads up on diseases that could affect people in her age group and asks her doctor about them. “I have changed my lifestyle completely and follow everything that is healthy. But still one can't be sure of what goes on inside your body. It is better to go for screening tests on a regular basis.”

But are these investigations really doing her any good? Verma represents a growing number of proactive people who rely on medical investigations to determine the state of their health without realising that these tests may be doing them more harm than good. Dr Balram Bhargava, professor of cardiology at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, says he gets many patients in the outpatient department who come to consult him with a thick file of self-prescribed tests―echocardiography, electrocardiogram, treadmill test and even angiography. When Bhargava asks them why they underwent these tests without the doctor's advice, most people say it was to save time.

Unnecessary medical investigations, says Bhargava, is a huge problem in India as it adds to the spending on health care without improving its quality. Studies in the US and the UK state that more than 20 per cent of medical investigations done on patients are absolutely of no use and many are done in conditions which could be dealt clinically by a physician. Doctors say that in such cases, the investigations don't add to the quality of medical care. The impact, in financial terms, is more in developing countries like India where only 5 per cent of the population has medical insurance or third party insurance.

Dr Arun Gadre (left) with Dr Abhay Shuka.

Dr Arun Gadre (left) with Dr Abhay Shuka.

To address the growing problem, Bhargava and a few colleagues at AIIMS founded the Society for Less Investigative Medicine (SLIM) last year to educate physicians and patients about the harm excessive investigations could do. As part of SLIM, Bhargava has asked doctors from across the country, in both public and private practice, and across specialisations, to come up with guidelines for medical practitioners to follow before prescribing medical tests. Besides, it could be a guidebook that patients could refer to and take an informed decision. “We have already come up with guidelines and set protocols which a cardiologist may follow while recommending medical investigations to his patients,” says Bhargava. “It would help a doctor figure out when he should order a simple ECG and under what circumstances should he prescribe an angiography to his patient. We are working on such guidelines in every specialisation, be it paediatrics, orthopaedics or oncology.”

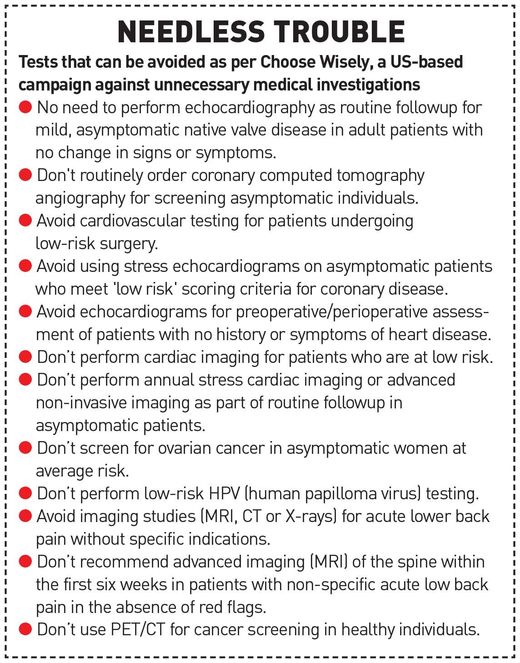

SLIM has been created on the lines of Choose Wisely, a campaign launched in the US in 2012 against unnecessary medical investigations and treatment. The campaign was so popular that the UK and 12 other countries, including The Netherlands, Australia and Japan, followed its recommendations.

If a medical investigation is unnecessary, then why is it conducted in the first place? There are patients who either self-prescribe or insist their doctors prescribe tests. Some doctors do it out of ignorance, there are others who do it for cuts from diagnostics companies, and some do it under pressure from the hospital management, which is eager to generate revenue.

“There have been instances of doctors getting kickbacks and cuts,” says Dr Samiran Nundy, gastroenterologist at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi. “The temptation to do unnecessary investigations is high. A CT scan may get a doctor up to Rs1,500. Besides, there is an institutionalised system of so-called ‘facilitation charges’ or fees for ‘diagnostic help’ given to the physicians who refer patients regularly and for expensive procedures.”

Dr Arun Gadre, who wrote Voices of Conscience, a book that takes a look at corruption in medical practice, says a young pathologist who works in a mega city revealed to him that out of 150 doctors he met as part of a promotional campaign, only two agreed to send their patients without expecting any commission. “It is a deep-rooted problem that is spoiling the relationship between the doctor and his patients,” says Gadre. “It would have disastrous consequences.”

However, there have also been cases where doctors have complained against such malpractices. For instance, when Dr Himmatrao Bawaskar of Maharashtra got a cheque of 01,200 from a diagnostic lab as 'professional fee' for referring a patient, he immediately informed the Maharashtra Medical Council.

All of it put together constitutes 20 per cent of the total spending on health. A major factor for the growing burden of unnecessary medical investigations is annual health checkups. "These tests do more harm than good to people,” says Dr Rohini Handa, senior rheumatologist at Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals, New Delhi. “If you don't have any symptoms or high susceptibility to any particular disease, why should you get yourself investigated unnecessarily?”

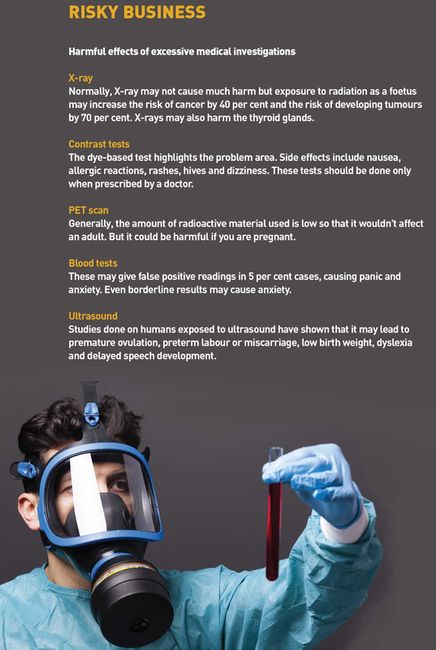

Doctors say there is a possibility that a test may show false positivity. In fact, studies show that its chances are as high as 5 per cent. Besides, even if your test results are on the margin, you may go for further tests to verify it, thus getting caught in a vicious cycle of doubt. Research shows that a single 12-lead echocardiogram fails to diagnose about 45 per cent of acute myocardial infarctions (heart attacks). Similarly, a good clinician may diagnose malaria more accurately and faster than a blood test.

On the other hand, random investigations may detect clinically unimportant diseases for which patients are then over-treated. “I have seen many people who get their tests done from three different labs to verify the diagnosis and still they are not satisfied,” says Dr Jeevan Jyot Baia of BLK Hospital, New Delhi. “They tend to go for repeated checkups thereafter. We have many such regular patients. If we try and counsel them, they just switch the hospital.”

Researchers at Cochrane Library, an online database, reviewed 14 medical surveys among 1,82,880 people. They found that the health checks did not reduce morbidity or the risk of illness and it also had no effect on the risk of death.

In fact, there are many undesirable effects of general checks. It could lead to overdiagnosis, where the tests pick up a disease that would not have affected the quality of a person's life or longevity had it not been detected. Such test results could lead to more tests, which means more risk, worry, income loss owing to absence from work, problems getting health insurance and potentially increased health care costs.

Medical science, says Handa, is all about possibilities and probabilities. The human body is not a machine with definite functions and parts. Each body may behave differently under similar medical conditions. There is an amazing coordination between millions and millions of cells which form the organs, and any fault anywhere may lead to a medical problem. So, anything is possible. For example, a simple headache may have hundreds of causes ranging from simple stress and gastric problems to complex lymphomas and tumours. But a doctor may not ask his patient to go for a PET MRI scan on his first visit unless there are very strong symptoms indicating tumour.

Doctors say it is the growing distrust between patients and doctors that is pushing them to take up defensive medicine―an ultra proactive approach to rule out any disease. But it subjects patients to many unnecessary tests. “We were taught in medical college that while dealing with a patient, one has to rely primarily on medical history (80 per cent) and clinical diagnosis (15 per cent), and then support it, if needed, with medical investigations in 5 per cent cases,” says Dr Anand Malviya, rheumatologist based in New Delhi. “Now doctors follow it in the reverse fashion. And there are various reasons for doing so.”

In an article for The BMJ, British cardiologist Ben Richardson described how during a cardiology ward round, a consultant listened to a patient’s heart and by merely listening to the pattern of his heart beats, he postulated that the patient had severe “aortic stenosis with moderate mitral regurgitation”. Richardson, in his article, says that subsequent review of the echocardiography report confirmed that the consultant was right.

Patients read a lot on the internet about their symptoms and related diseases before they consult a doctor. They verify each and every prescription and diagnosis. “Having read all the possibilities, they want a quick diagnosis,” says Dr S.K.S. Marya, orthopaedic surgeon at Max Hospital in Saket, New Delhi. “Besides, patients are getting aggressive with doctors. They don't understand the complexities of human body and limitations of medical science. This discourages the doctors from taking a systematic approach,

which they used to follow a decade ago.”

The deteriorating quality of medical education is adding to the problem. “Most medical graduates these days are not hands-on doctors,” says Malviya. “They rely more on medical investigations and are weak clinicians. It is an easy way out for them.”

Dr Rohini Handa | Aayush Goel

Dr Rohini Handa | Aayush Goel

Ignorance on a doctor's part, however, could be addressed by senior doctors. Marya, for instance, has a strict protocol which every junior doctor follows for prescribing tests and the course of treatment. “The problem can be sorted out by senior clinicians in every department,” he says. “This way we can bridge the gap in medical education and make them hands-on doctors.”

A survey conducted in the US under the Choose Wisely campaign to find out the behaviour of doctors who prescribe extra tests showed that more than half of the physicians thought that they were in the best position to address the problem and had the ultimate responsibility for making sure the patients avoided unnecessary care. Yet, at the same time, more than half of them said they would give an insistent patient a medical test they knew was unnecessary.

Dr Balram Bhargava

Dr Balram Bhargava

“It is, thus, essential for a patient to be informed about the pros and cons of excessive tests,” says Nundy.

“Preset protocols and guidelines may also address the problem. Patients have to be informed that excessive tests have their side effects―adverse drug reaction, radiation exposure, faulty tests results, psychological stress, etc.”

Anant Phadke

Anant Phadke

So, how can the problem be managed? Ideally, says Marya, there should not be any distrust between patient and doctor. But in these times of fraught doctor-patient relationship, there would always be doubts. “And, because the problem is multi-factorial, the solution, too, should take into account every aspect of the issue,” he says. “First, there is a need to keep a tab on hospitals. These could be random inspections where an outside regulator may check the records to find out how many investigations have been conducted in a set period of time and how many of them showed results. If the ratio of the total number of CT scans ordered by a department and scans on the basis of which the doctor could form a diagnosis is high, it means the doctor is prescribing unnecessary investigations.” The audits could be done internally or externally in any hospital, including government-run.

“Cut-based practice is rampant across India,” says Dr Nandakishore Dukkipati, bariatric surgeon and member of Medical Council of India. “We need stringent laws to prohibit these practices. At present, diagnostic centres are run like shops. We need a stronger body to govern these labs and imaging centres so that their behaviour could be studied.”

In the US, they have Stark Law, which prohibits any physician from referring his patient to any diagnostic lab with which he has a personal link. In case of violation, the physician could even lose his licence to practice. “We need such strong laws in India,” says Dukkipati.

Dr Ashok Seth, interventional cardiologist and member of MCI, feels that though it is criminal to subject the patient to an unnecessary test as all tests, especially those involving radiation, have side effects, he is yet to come across a doctor who does it deliberately. Commission-based practice, however, is rampant, he says, and needs to be curbed. “The MCI is working on it,” he says.

One way to do it would be to make the Clinical Establishment Act, 2010, stronger, says Dr Anant Phadke, a Pune-based health activist. As of now, it only lays down guidelines for treatments and looks at the minimum standards required for any medical facility to function.