Technology has made it easier to pin down a wandering minstrel. In Jaydev Kenduli, a village in Birbhum district of West Bengal, nearly 200km from Kolkata, roams Tarok Das, a curly-haired portly Baul singer. The rural Baul tradition of the state found its roots in this village, named after the poet Jayadeva, which also hosts the Baul mela on Makar Sankranti every year.

A strap hangs around Das’s neck along with a bunch of colourful beads. At the end of the strap is a mobile phone. If the caller can’t speak Bengali, then Das hands over the phone to a friend who translates.

Bauls are said to be half-sanyasis whose mellifluous songs are a mix of Tantra, Sufism, Buddhism and Vaishnavism. This is a spiritual sect which is said to have originated in the 15th century and renounced the worldly life.

Settling down under a large, gnarled and solid banyan tree in the village centre, Das explains that owning a mobile brings no dissonance in his belief system. There is no desire for a phone or other material things, it is rather a necessity in today’s times. “I need it for people to reach me to communicate and proliferate the philosophy. I have been called to JNU [in Delhi] next month for a performance. That way more people will get to know about the Baul tradition. If they couldn’t reach me, how would this happen?” he asks, breaking into a spontaneous song, using just a matchstick to keep time on the matchbox, tapping his feet with the ghungroo-laden ankles. If he gets booked for a performance, he gets, on an average, return train tickets and Rs 30,000 for the troupe of six.

Baul singers generally use either the ektara (single string) or dotara (dual string) instrument to sing their stories to whoever cares to listen. The tradition was included in the list of ‘masterpieces of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity’ by UNESCO in 2005. It is said to have had a big influence on poet-writer Rabindranath Tagore’s music. Tagore’s abode, Santiniketan, is just 40km from Kenduli. Lalon Fakir was one of the most well-known exponents in the 19th century, while Kerala-based Parvathy Baul, 40, who runs a school that teaches Baul singing, is considered a popular face of the tradition today.

“Baul is being, not singing. The mind, body, soul is all Baul,” explains Das when he finishes the song. The community follows a didactic system. Gurus take students under their wing and pass on wisdom acquired over generations. Slowly students are advised to step out of the guru’s shadow when the guru feels they are ready. Now they can collect alms, perform and share without the guru’s oversight.

Like, in Das’s case, he built an ashram on his own in 1993. According to the Bauls, an omnipotent supreme power runs the universe but it is formless (nirakara). This formless entity reveals itself to a ‘few fortunate ones’ as a spark of light, sometimes. The teacher in their community is accorded the highest reverence instead of this formless entity.

The core philosophy is introspective, self-reflective and timeless. “Knowing the self and turning the mind’s eye towards itself is the ultimate goal. Once you understand the unity/interconnectedness between mind-body-soul, lyrical expression becomes effortless,” he says. What is passed on to students is one’s understanding of this interconnectedness through personal experience. However, the core wisdom of panchabhoot and chhetatva is timeless. These six tatvas are what rules the mind-body. The mind-body is the garden of highest devotion and it seeks to remain devoted to the Baul form. Detachment and sacrifice are other core elements. “Whatever a Baul becomes is a result of his devotion to his teacher and the form,” says Das.

“Look at this, Baul bhesh,” Das says in a somewhat childlike tone, pointing to his patchwork kaftan-like kurta that he slips over his simple attire. The patchwork is symbolic of the begging aspect of the tradition. The clothing is called guduri. It is also meant to be a representation of unity of ideas. The singing form is annotated, which means the singer breaks into spoken word explanations. “The mystical power of Baul singing can take you into a state of trance,” teases Das lightly.

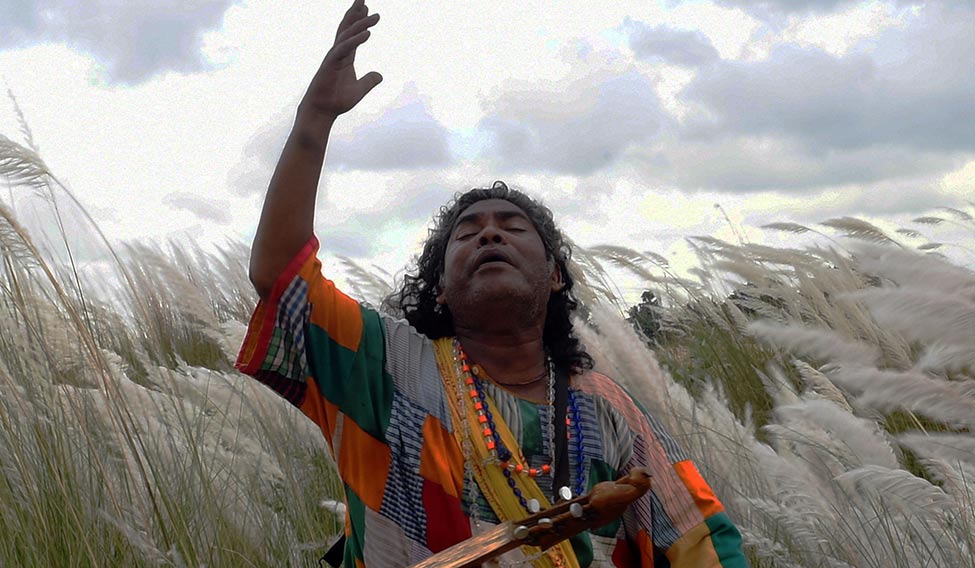

Wearing his colourful costume, holding the ektara, he walks onto the banks of the Ajay river, which is covered with the beatific kash flowers, swaying in their symbolic white glory. He begins a beseeching for the rain to fall, singing deeply, opening his arms wide and moving around with the music. “In the monsoons, the river swells up and becomes a furious being. In the winter months, it dries up and becomes like a beggar, asking for rain. Somewhat like a Baul singer....” he speaks of his poetic lament.

The last lines of his song trail off. Das looks up at the sky, closes his eyes, and greets the first drops that fall.

‘Baul’ed over

Nobel laureate Bob Dylan is said to have referred to himself as ‘America’s Baul’ when he first visited India in 1990 to attend the wedding of folk singer Purna Das Baul’s son in Kolkata. The Baul tradition has a liberal interpretation of love, and the songs have stayed mostly oral in form. Despite constituting a fraction of the Bengali population, Bauls have had a considerable influence on the state’s culture.