Old blankets, discarded hoardings and banners of political parties, all wrapped around bamboo poles form the walls of dark, dingy hovels clustered together at Kanchan Kunj on the banks of the Yamuna in New Delhi. The squalid living conditions and rank poverty, however, do not matter to the 46 Rohingya families here. What matters is that they are free. Free to dream, to study, to work.

Among the 225 residents is 20-year-old Tasmida Zuhar, a class XI student. She hopes to become a lawyer and work for the rights of her community. This dream is beyond anything that she could have nurtured back home in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. There, Rohingyas cannot study beyond tenth grade because there are no colleges within the enclosed area where they are kept, and they are not allowed to travel out of the reservation.

Tasmida’s family members, who were reasonably prosperous businesspeople, decided to leave Myanmar ten years ago, after her father was jailed twice for reasons like plying his cargo boat beyond the reservation. The family of nine got onto a boat and rowed to Bangladesh, 30km away. They lived in Cox’s Bazar for four years. “But the opportunities were few, so we began saving for crossing over to India,” says her brother Mohammed Salimullah, 34, who runs a general store.

“You have to grease palms on both sides of the border. They charge a few thousand rupees per person. If we are caught, we land up in jail, like many of our friends have.” Once safely in India, the family decided to head to Delhi, where they settled down in 2012. The family has grown in numbers with marriages and births. One of Salimullah’s brothers is studying law. His sons, born in India, are in play school.

The Rohingyas have been crossing over into India for several years, and the most recent wave was in 2012. At the nearby Shahin Bagh slum is Dil Mohammed, who came “before the Kargil war”. He came with his wife and son, rowing stealthily into Chittagong. From there, they moved to Dhaka and, then, to Kolkata by bus. Today, his family has grown to ten members.

Key to freedom: Mohammed Tahar, a Rohingya in Delhi, displays his refugee card issued by the UN | Sanjay Ahlawat

Key to freedom: Mohammed Tahar, a Rohingya in Delhi, displays his refugee card issued by the UN | Sanjay Ahlawat

Recent remarks by Kiren Rijiju, Union minister of state for home affairs, that all 40,000 Rohingyas in India would be sent back have spread anxiety among the community, but the refugees are adamant that they will not return to face persecution and death. They are not even allowed to get married without permission in Myanmar. It is another matter that Myanmar, which does not recognise these people as its own (calling them Bengali immigrants) has shut doors on them, and no other country is ready to receive them, either.

Salimullah, and another Rohingya, Mohammed Shaqir, have filed a petition in the Supreme Court with the help of senior lawyer Prashant Bhushan against their deportation. “We will not leave,” says Salimullah. On September 18, the Union government filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court, stating that the Rohingyas posed a security threat and that the government should be allowed to take a decision on their deportation. The apex court will now take up the matter on October 3. However, even as India explores deportation plans, many families here are working on bringing over their relatives, coordinating their movements over WhatsApp.

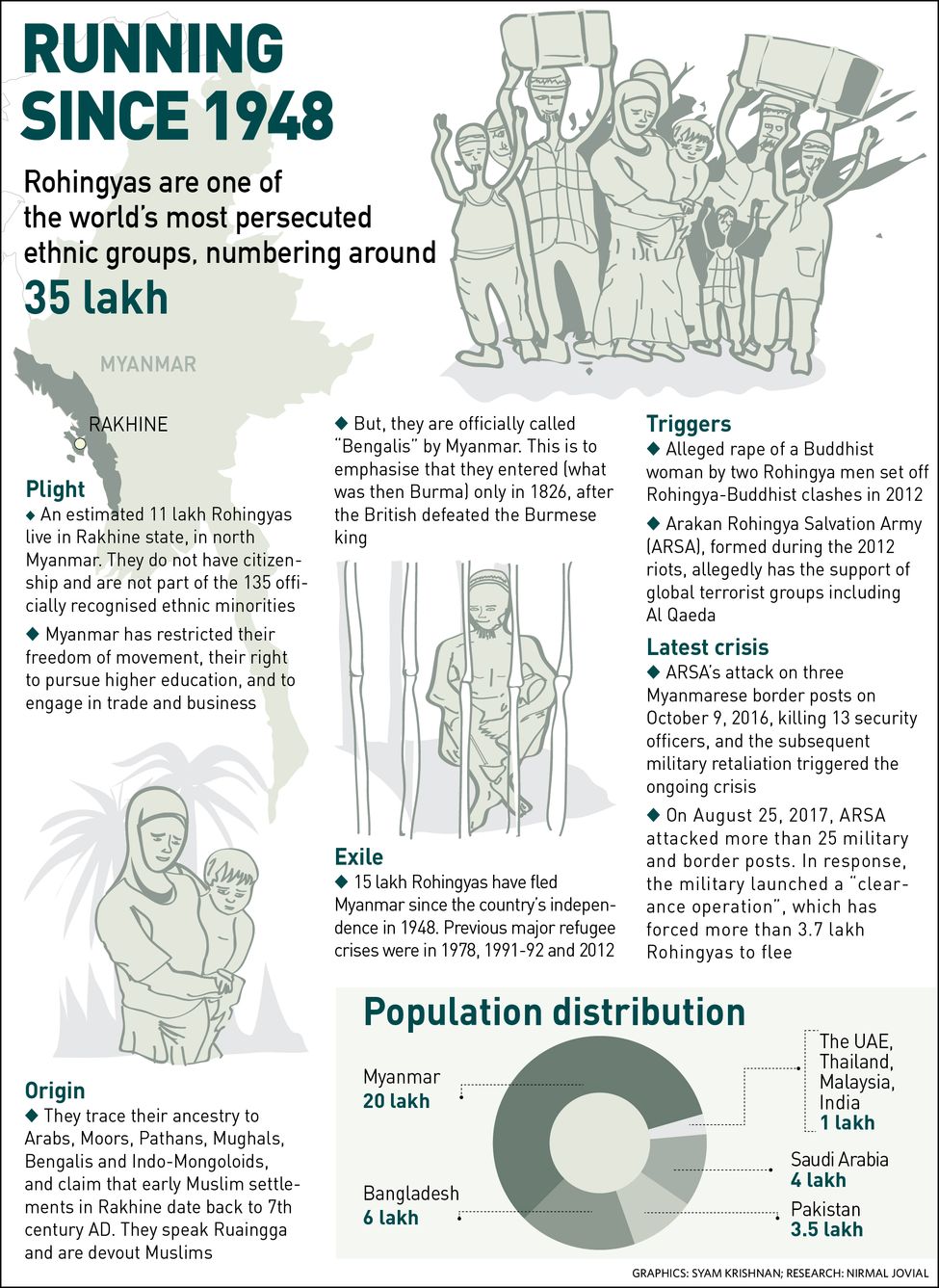

The Rohingyas are the most persecuted people in the world according to the United Nations, and their exodus from Myanmar has become a matter of concern for neighbouring countries. Bangladesh, for instance, has witnessed the influx of three to four lakh Rohingyas since the most recent flare up. Bangladesh High Commissioner to India Syed Muazzem Ali met foreign secretary S. Jaishankar on September 9 to discuss the issue.

While Bangladesh is the initial destination for Rohingyas, most of them would rather head ultimately to India, creating a multilevel headache for New Delhi. It upsets the demographics and puts extra pressure on an already strained infrastructure. The government also needs to look at the security and strategic angles. Myanmar’s help is crucial for India’s own fight with the insurgents in the northeast, like in the case of the June 2015 surgical strikes targeting insurgent camps in Myanmar.

“People are making it a communal issue,” says former ambassador to Myanmar G. Parthasarathy. “India has never agreed to keep the refugees indefinitely. Eleven million Bangladeshis were sent back and the Sri Lankan Tamils are being sent back now as the conflict is over. Even the pro-democracy asylum seekers from Myanmar have returned now that the government has changed. Sending back Rohingyas is consistent with our policy. It is another matter if local politicians, for votes, gave the immigrants ration cards, but that is not government policy.”

Tasmida Zuhar, a class XI student, is the most educated Rohingya girl in the Kanchan Kunj camp. She wants to become a lawyer | Sanjay Ahlawat

Tasmida Zuhar, a class XI student, is the most educated Rohingya girl in the Kanchan Kunj camp. She wants to become a lawyer | Sanjay Ahlawat

India is not a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, although it has hosted refugees from Afghanistan, several African countries, Bangladesh and, most importantly, Tibet. There are over two lakh refugees in India as per figures available with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Some have become naturalised citizens, like Hindus from Afghanistan and Pakistan and, most recently, Chakmas from Bangladesh.

“We don’t want to accept the unwanted people of our neighbouring countries. It is a well established part of our border and neighbourhood policy, it transcends the government in power,” says Parthasarathy. “Open the door and soon Nepal will dump its Madhesis, Bhutan its Nepalis, and then what does one do?”

India’s strong anti-Rohingya position is often contrasted with its policy towards other refugee groups. Former ambassador and president of the Ladakh International Centre P. Stobdan, says, “There are political and security reasons for granting refugee status to certain people and denying it to others, and rightly so. Let the UN say what it wants. If it is not convenient to us, it isn’t. Why cannot other Islamic states absorb the exodus?”

Rajiv Chander, India’s ambassador and permanent representative to the UN, says, “Like many other nations, India is concerned about illegal migrants, in particular with the possibility that they could pose security challenges. Enforcing laws should not be mistaken for lack of compassion.”

Granting refuge to people fleeing neighbouring countries can have long-term repercussions. “Look at the Tibetans, special guests for over 50 years. India failed to convert them into a guerilla force that would return and take on China. And now, there is talk of naturalising them. China has stood to gain. It has Tibet under it, while the dissenters are out,” says Stobdan.

But, couldn’t Rijiju have toned down even while stating India’s official position? Because the bottom line is that India cannot send back 40,000 people when Myanmar is not willing to accept them. India will have to use its diplomatic skills with affected neighbours to come up with a solution.

Myanmar is very important strategically and is quick to anger. Parthasarathy recalls the time in 1995 when the Indian and Myanmarese armies had agreed to a joint operation to wipe out insurgent dens in the jungles of Myanmar. “Myanmarese soldiers died in that operation. But, even as it was on, vice president K.R. Narayanan announced the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding for Aung San Suu Kyi, who was then in the opposition. The Myanmarese army was furious. We completed the operation, but the mopping rounds could not be completed.”

A spokesperson for the UNHCR said it had not received any official communication from the Indian government regarding changes in its approach on refugees and that there were no reported instances of deportations. The spokesperson also said although India was not a signatory to the refugee convention, it was party to a number of international human rights instruments. Further, the principle of non-refoulement (not sending back refugees to a place where they face danger) is part of customary international law and, therefore, binding on all states.