They are sitting on a gold mine, literally. Yet, residents of Kolar Gold Fields (KGF) travel 100km every day to Bengaluru, seeking their fortune. They do odd jobs there, working eight hours a day, all for Rs5,000 a month. Take, for instance, Naresh Kumar, 26. He leaves home at 5.30am, travels three hours by train to reach Bengaluru, works as a daily-wage labourer and returns to a dingy hut—home to his family of six and a hearth for a flickering hope of a better future. Naresh is just one among the 30,000 men and women in KGF who commute to the state capital to work daily, but cannot afford to live there. Fifteen years after the Bharat Gold Mines Limited (BGML) shut down and with no new industries or job opportunities coming up, KGF has lost its lustre. It is an irony that poverty and prosperity have the same address here. If the BGML township—spread across 12,000 acres—has 12,000 families residing along 125 rows of hutments or camps built by the British, the 10x10 huts are surrounded by 13 grey tailing dumps—mining waste with gold traces, estimated to be worth Rs25,000 crore.

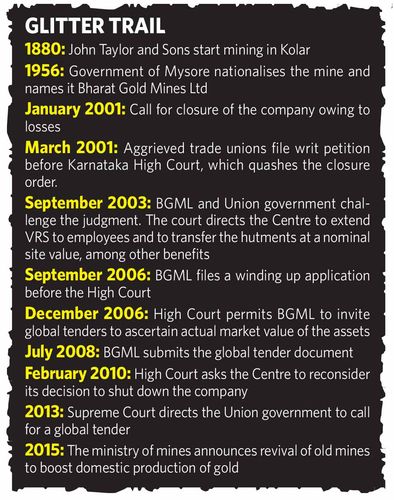

Sounds unbelievable, right? But BGML, in the last 135 years, has extracted approximately 800 metric tonnes of gold. But in 2001, decades after the Indian government took over the mines in 1956, the Board of Industrial and Financial Reconstruction ordered the closure of BGML, saying it was no longer economically feasible. Mining had become unviable as cost of gold extraction was high—Rs1,000 per gram of gold—and the gold prices were as low as Rs400 per gram. With the call for closure came a slew of writs and appeals by trade unions and the government.

In 2006, the Union cabinet decided to call for a global tender to ascertain the market value of BGML's assets. As per a 2008 tender document, the 12,000 dwelling units of the BGML township were listed in the assets put up for sale along with its operational mining area, British bungalows, schools, a 400-bed hospital, temples, churches, mosques and government institutions like the Bharat Earth Movers Limited and the National Institute of Rock Mechanics. In 2010, a division bench of the Karnataka High Court dismissed the global tender proposal and directed the Union government to reconsider its decision to close down the mine. “Transfer of assets to any buyer without examining if revival was possible is not in the interest of the company or the employees,” the court said.

In 2013, the Supreme Court, however, gave the Centre the permission to float a global tender. In 2015, the Union government decided to revive old mines, including BGML, to boost the domestic production of gold. A government document submitted to the Supreme Court—the Davy John Brown 1996 techno-economic feasibility report on resource estimation—states the BGML township has 31 million tonnes of tailing dumps (one tonne of dump yields one gram of gold on processing). Moreover, only eight of the 26 gold reefs in KGF have been explored so far, meaning fresh excavations are possible in the remaining reserves.

With this, former employees hope to get their jobs back in the mines. But with private players in the fray for the global tender, there is no job guarantee. Also, the High Court had directed the employees, who had 16 trade unions, to form a single cooperative society and form a company along with a financier. The idea was to call a global tender and keep the highest bid at abeyance, as the employees’ company was to be given the first right of refusal, or first chance to bid for the mines at the same price as the highest bid. The first right of refusal rule did more harm than good as the employees have now regrouped into four unions, with each one wooing a different investor. The joint venture would have three directors—one from the union and two from financiers, who would share the profits with the employees. But this has evoked individual aspirations among union leaders, who are now fighting among themselves.

For more images: Kolar Gold Mine: Then and Now

The employees, therefore, hope to hold on to their hutments at least. Says Pavithra, Naresh Kumar’s wife, “Our hutments are our only assets, and the government is now trying to sell them. We know there are gold deposits hidden beneath our houses, but look at our lives. My husband travels to Bengaluru daily for work. His unwed sister walks 4km every day to work in a garment unit for just Rs3,000. My father-in-law works as a security guard. No one can work in the mines even if it is revived, as it is dangerous.”

KGF, famous for gold deposits visible to the naked eye, saw Tipu Sultan and later the British excavate gold by employing men from neighbouring Tamil Nadu. It has produced the richest gold deposit from one of the deepest underground mines of the world. If the gold strike (length of reef) stretches to 7.3km, the underground mine goes 3.2km deep and has 1,400km of tunnel work, which is now waterlogged and therefore risky to revive operations.

The Mines and Minerals Development and Regulation Amendment Act allows only fresh auctions of the mines, which has created unrest among the employees. “Gold value has increased more than ten times, though cost of extraction has gone up only two-three times. It is feasible now,” says Dass Chinnasavari, president of KGF Citizens' Protection Forum. Under the special termination benefit package offered at the time of shutdown, only 2,812 of the 12,000 families, who were on the rolls of BGML, were given ownership rights to the hutments. “We want the government to exclude the BGML township from the tender and allot hutments to all 12,000 families,” says Chinnasavari.

Former employees also argue that after BGML and BEML, no new industries have come up in KGF, despite the availability of skilled manpower. Only 3,000 people are employed in BEML, says Chinnasavari. “BGML has accrued bank loans of Rs500 crore and Rs80 crore of employee dues,” he says. “The government should raise that money by extracting gold from the cyanide dumps, which can easily fetch Rs25,000 crore. This money should be used to develop industries and jobs in the district.”

But can the gold mines be revived? According to Dr V. Venkateswarlu, director of the National Institute of Rock Mechanics (NIRM), which was founded in the research and development lab of BGML in 1989, there is a risk of rockbursts as BGML lies on the Mysore-North fault, prone to microseismic activity. “The underground mines are now waterlogged and hence unsafe for mining,” he says. “A shallow mine would rule out such fears. A fresh shaft is safer than an existing mine as the township is sitting on the mines. While, the cyanide dumps across the township need to be carted out as it is a health hazard [causing silicosis], the dumps can yield 0.5gm to 1gm of gold per tonne, if treated with advanced methods now being used in Australia and South Africa.” Dr A. Rajan Babu, principal scientist of NIRM, says BGML area has immense potential for fresh excavations. “Open pit mining is recommended as we have better technology today.”

Gold or no gold, “We need some decent job and income,” Prabhu, a scavenger. “But I wonder if the mines here will be revived at all. It has been a long wait.”