Assistant sub-inspector Dilip Shirke could well be a symbol of all that is wrong with the Mumbai Police. On the evening of May 2, Shirke, attached to the Vakola police station near Santa Cruz, got into a fight with inspector Vilas Joshi, who was the station in-charge. In a fit of rage, Shirke pulled out his service weapon and shot Joshi dead. He later killed himself.

“Shirke used to pick fights with almost everyone. He had a peculiar brashness to his character,” said assistant commissioner of police Sunil Deshmukh, who is probing the shooting. Investigations revealed that earlier, too, Shirke had fought with Joshi for marking him absent. “Joshi was not wrong in marking him absent,” said Deshmukh. Shirke was a habitual absentee. He was also perennially irritable, forever worried about finding a good match for his daughter. His 24-year-old son was unemployed, adding to his woes. And, Shirke thought that the “system was against him”. His story is emblematic of the malaise affecting the Mumbai Police, especially the subordinate ranks.

Hundreds of policemen share Shirke's plight. His colleague Surendra Kashid remains deeply frustrated after serving as a constable for 20 years. Kashid's story, too, represents the systemic deficiencies plaguing the Mumbai Police when it comes to service conditions and benefits. “We want quality life. Otherwise, how do we survive and motivate ourselves?” asked Kashid. “We protect the people, but who will protect us?”

Kashid's parents live with his brother because his 180-square-foot quarters in the Mahim police colony is too small to accommodate everyone. A visit to the quarters revealed the neglect an average Mumbai policeman has been subjected to over the years. As we listened to Kashid's story, his son, who was suffering from fever, lay on a lean wooden cot by our side, occasionally getting disturbed by our conversation.

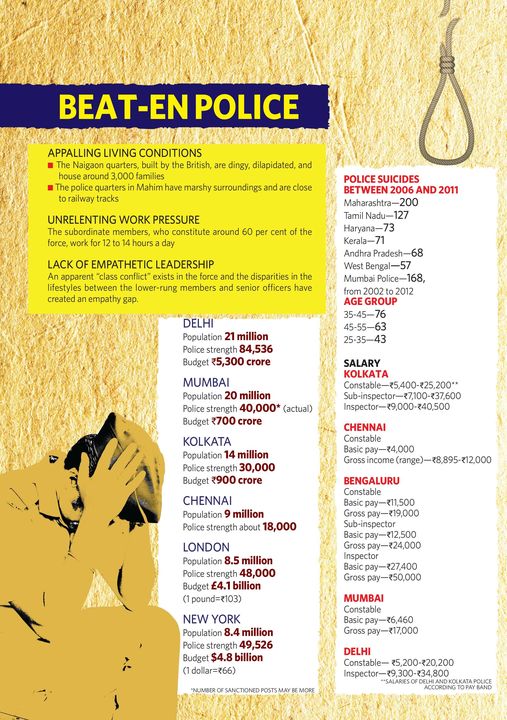

Graphics: Deni Lal

Graphics: Deni Lal

For the Kashid family, the kitchen doubles as a storeroom. Its ceiling is covered by patches of plaster to prevent water seepage. “We did this on our own. The PWD men do not help us,” said Kashid's wife. “We huddle like cattle in the living room, which is used by our two children as their study room. I use it for cutting vegetables as well,” she said.

The situation is not any different at the quarters of a sub-inspector attached to the Nirmalnagar police station in Bandra. “For the last five years, I have been going to the local PWD office. They keep telling me that they have no contractors to carry out the repair work. For us, it is an endless battle,” said the officer's wife.

The police quarters in places like Mahim and Naigaon cry out for improvement. The quarters in Mahim were allotted to the Mumbai Police after the staff of BEST (Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport) and the city courts refused to occupy them because of the marshy surroundings and the railway tracks next to the quarters. The Naigaon quarters are worse. Built by the British, these are dingy, dilapidated, and house around 3,000 families. “Once, our toilet roof leaked during the monsoon months. We had to go in with a brolly on our heads,” said a sub-inspector.

Pandurang Chougule, secretary of the Police Kutumba Samajsevi Sanstha, a police welfare organisation, said the Mumbai policeman remained a lone and neglected figure. “He gets paid little and has odd working hours. His family continues to live a life of relative deprivation. Even the slum dwellers seem to be entitled to better houses under various schemes. We are worse off,” he said.

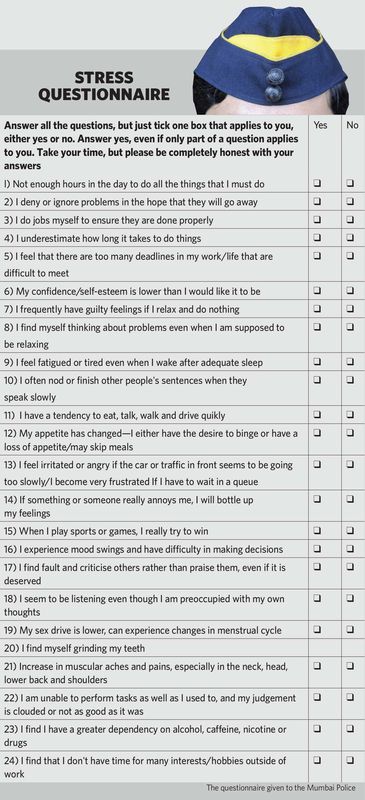

Such appalling living conditions and unrelenting work pressure are among the reasons that made Shirke turn violent. Moreover, these policemen receive no psychological support like clinical intervention or counselling. “Following the Shirke incident, we have advised the force to get its members examined every six months. We have specially framed questions which will give us a glimpse of the stress quotient of the members of the force,” said Dr Yusuf Matcheswalla, a psychiatrist attached to J.J. Hospital in Mumbai (see questionnaire). He said the disparities in the lifestyles between the lower-rung members and the senior officers created an empathy gap. “The Mumbai Police is among the very best when it comes to cracking criminals and their wily and dark activities. But the issue here is of exemplary leadership, of leaders who are rooted to the ground and who cultivate and radiate empathy for members of the force,” said former Mumbai Police commissioner and director-general of police D. Sivanandhan, one of Mumbai Police's most celebrated officers.

Insiders said an apparent “class conflict” existed in the force. “These are separate and distinct worlds, that of the DCPs and the ACPs. The senior PIs (police inspectors) are a separate breed altogether,” said a senior officer.

Mumbai Police commissioner Rakesh Maria said efforts were on to improve the mental health of the force. He said the Vakola shooting should not be seen in isolation because such incidents were occurring with alarming regularity. The Bombay Psychiatric Society and the Bombay Psychological Association have teamed up with the Mumbai Police to tackle the challenge head on. “What we are doing now is aimed at understanding the emotional and psychic dynamic of the policemen on the ground,” said Dr Matcheswalla.

Deshmukh, who handled high-profile cases like the suburban train bombings and the Abu Salem case in the past, said something substantial had to be done on the ground to improve the living conditions of the policemen. Several serving and retired officers said poor accommodation was the root cause of the problem and the onus was on the political class and the senior officers to find a solution. “The emotionally stretched and mentally stressed Mumbai police personnel work and survive like speechless animals.... Most of them and their family members are deprived of even basic necessities of human survival. As a result, they are always in a mood like an erupting volcano,” said an order passed by the Maharashtra State Human Rights Commission in March 2007, following a complaint filed on the issue.

The order noted that the depression suffered by the police personnel adversely affected the security of the city. It said the policemen “are under incessant physical and mental stress and strain and are policing the city with tears in their eyes.” Eight years later, the situation has not changed. No wonder the Mumbai Police records the highest number of suicides compared with other police forces (see graphics).

The housing crisis got worse after the Maharashtra State Police Housing and Welfare Corporation Limited lost administrative approval rights over housing schemes. More than 30 files pertaining to housing schemes are pending, although the corporation has been put back in charge by the Devendra Fadnavis government. Even a ratified approval from the corporation, however, does not amount to much, if the public works and the finance departments are not cooperative enough. Maharashtra is the only state which has failed to spend the money earmarked by the Union home ministry for its mega city police scheme even though police residential quarters at Colaba, Mahim, Kalachowki, Matunga, Dadar, Naigaon, Charkop and Ghatkopar are “stinking, hazardous, uncomfortable and destructive”.

Such deprivations could have added to the increasing criminal nature of the police. The average policeman does not seem to have the right mix of values. “The poor integrity quotient is a likely fallout of the relentless exposure to high net-worth individuals in dire need. Extortion has been a historical fact with the Mumbai Police,” said a former top Mumbai police officer. In the heyday of the Mumbai underworld, in the early 1980s, in, a section of the police got close to the dons. “It was the salaam-dua culture. You ensure your safety by paying obeisance to the dons,” said another retired officer. The lack of effective leadership, both of the service and the political class that oversees it, has also played a role in worsening the crisis.

Under the Congress-NCP regime, the NCP had the upper hand in deciding the police commissioner. Insiders said NCP leader Sharad Pawar always had the final say in the matter. Home ministers like R.R. Patil, Jayant Patil, Chhagan Bhujbal and Padamsinh Patil did little to improve the quality of lives of the Mumbai policeman. Many say that decline began when Padamsinh Patil became home minister in 1993. Under Bhujbal, the politicisation of the force was complete. The fissures within the force were palpable during its response to the 26/11 terrorist carnage. After the attacks, R.R. Patil, who was the home minister, and Bhujbal traded charges of lacking courage to step out of their residences during the attack.

Retired officer Vasant Tajne, who had worked with the Maharashtra Anti-Terrorism Squad, said the policemen were troubled by inconvenient postings, long working hours, lack of holidays and poor living conditions. “You can't say to your senior that your duty is over. The problem is of post-duty working hours,” he said. “The average policeman has just too many hats to wear simultaneously, ranging from maintaining law and order, participating in bandobast drills and doing VIP duties, apart from handling crises like communal tensions.”

Unending hours of work is another major worry for the policemen. The number of cognisable offences registered at a police station is around 1,200 a month on an average. Besides, 10,000 non-cognisable offences are registered annually on an average. Apart from regular police work, the long hours of VIP duty, too, take a toll. “The long hours cause stress, both physical and mental,” said a senior IPS officer. The subordinate members of the force, who constitute around 60 per cent of the Mumbai Police, work for nearly 12 to 14 hours a day. Their commute itself takes around two to three hours. The appalling conditions at home adds to the trouble.

Equally worrying is the fact that the policemen are not given compensatory off days. They are forced to work on festival days and hardly get time to spend with their families on those days. The weekly off days, too, have become few and far between. As a result, the policemen are suffering from high blood pressure, insomnia, increased levels of destructive stress hormones, post-traumatic stress disorder, heart problems, depression, anxiety, maladaptive behaviour, dissatisfaction, fatigue and tension.

While Maria's efforts to address the psychological challenges faced by his men have been appreciated, many officers feel that a knee-jerk reaction would be counterproductive. Special Inspector General of Police (administration) Archana Tyagi said there was the need to streamline the system by which the mental welfare aspects of the policemen were handled. Although she refused to comment on Maria's efforts, she said it was important to have holistic and systematic efforts in this regard. “Piecemeal and half-hearted measures are not going to yield the necessary benefits in the long run, and should be shunned,” said Tyagi.

Maria, however, is a natural leader and is respected by everyone. “He is thoroughly aware of all aspects of policing. So we look up to him as our leader and motivator,” said a police officer attached to the Tardeo police station. But leadership has always been a deeply debated issue in the Mumbai Police. Following the 26/11 attacks, commissioner Hassan Gafoor had been roundly criticised for failing to lead the force effectively. In an interview with THE WEEK a year after the attacks, Gafoor said he was hamstrung after a section of his officers refused to cooperate with him. “Covering up goof-ups by subordinate officers often passes off as leadership quality,” said a former top Mumbai cop.

Tyagi said the emotional investment the average cop brings to the table by making himself available round the clock for the service of the public was enormous, and welfare measures for the policemen should be framed and implemented keeping in mind this central aspect. “The subordinate policeman should be treated with respect,” she said. “He should never be talked down to, but talked to. It can work wonders for the collective well-being of the police force.”