Shabnam Yusuf had an arranged marriage in December 2016. Twenty-one years old then, the Delhi girl wanted to pursue higher studies. But her parents told her they had found an excellent match for her. He had a good job at a pharmaceutical company, they said. Reluctantly, she agreed. She had long conversations with her fiancé on the phone, and he seemed nice.

The nice man turned into a beast on their wedding night, and her romantic idea of marital bliss died a brutal death. Shabnam pleaded to her husband that she was unwell, but he did not listen. He raped her several times, until she fainted. The next day, she told the women of the house what happened. They said it was normal, and remarked she might not have been prepared for it.

Shabnam left her husband’s house after a few months. As her parents were not supportive, she took refuge in a women’s shelter. She went to the police, who filed a case under Domestic Violence Act, and attempted mediation between the couple. But that was not what she wanted. She wanted justice.

However, according to India’s rape laws, Shabnam’s husband did not commit any crime. Marital rape is not recognised as a crime under Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, which is invoked in cases of rape. An exception to marital rape has been written into the law as “Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape.” Shabnam has filed a public interest litigation in the Delhi High Court, asking the exception to marital rape to be struck down as unconstitutional.

The rape laws make a distinction between rapes by strangers, rapes by estranged husbands and rapes by husbands. Section 375 and Section 376 are invoked in full in cases of stranger rapes. When a woman accuses her estranged husband of raping her, the crime is bailable and the prescribed penalty is two to seven years in jail. However, if a woman accuses her husband of raping her, it cannot be taken up under these sections.

If the distinction goes, the definition of rape, broadened after the gang-rape of a woman in a bus in Delhi in 2012, would apply to marital rape also. If a man forcibly has sexual intercourse with his wife without her consent, or has any other forced penetrative sexual activity such as anal sex, oral sex or insertion of a foreign body into her vagina, urethra or anus, she will be able to file a case of rape. If the woman is unconscious when the sexual act is performed on her, that could also amount to rape.

Aayush Goel

Aayush Goel

Many lawyers and activists say the exception to marital rape is arbitrary, and unfair to married women. It is considered a relic of colonial law dating back to what Justice Mathew Hale of England wrote in the 1600s: “The husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract, the wife hath given herself in kind unto the husband, whom she cannot retract.”

A married woman can take recourse under other laws, such as the Domestic Violence Act or Section 377, which deals with unnatural sex. She can seek divorce on grounds of cruelty. The Domestic Violence Act provides civil remedies for all sexual abuse at home. Under Section 498A, the dowry law, the maximum punishment for cruelty is three years in jail. The maximum punishment under Section 354, which is for unwelcome physical contact and advances, is seven years. Under Section 377, the maximum punishment is life imprisonment, but it does not distinguish between consent and no consent, and it criminalises only unnatural sex. However, for rape, the punishment ranges from seven years in jail to life imprisonment and even death penalty where the victim dies or is left in a vegetative state.

Also, a survivor of marital rape is not entitled to the state’s protective provisions such as compensation, free medical treatment, protocols for medical examination, protection of identity and legal assistance.

This “discrimination” has been challenged in the Delhi High Court by a clutch of petitions, including that of All India Democratic Women’s Association, RIT Foundation and Forum to Engage Men. The plea is to declare the exception to marital rape in the rape laws as unconstitutional. The argument is that it violates Article 14 by denying the married woman equality in access to rape laws, discriminates against her and, hence, goes against Article 15, puts curbs on her right to freedom as protected under Article 19 by taking away the right to say ‘no’, and violates her right to life as protected under Article 21.

“There is no rational basis for this classification,” said lawyer Colin Gonsalves, who is representing Shabnam in the High Court. “If under other laws, such as Section 354 and Section 377, there is no such exception, why do the rape laws make this distinction?”

In the light of the Supreme Court’s recent judgment on the right to privacy, it is argued that the married woman’s fundamental right to privacy is also breached. The judgment laid down that privacy included an individual’s right over his or her bodily and mental integrity, the person’s notion of gender, sexual autonomy, and the right to procreate.

Statistics reveal the enormity of the issue. According to a study done by the Research Institute for Compassionate Economics, married women in India are 40 times more likely to be raped, and one in every ten women faced sexual violence by their husbands. In 2005, just over 2 per cent of all rapes in India were by men other than husbands. It was also found that less than 1 per cent of rapes by husbands were reported.

According to a 2014 study carried out in nine states by the United Nations and International Center for Research on Women on intimate partner violence, a third of the men admitted to having forced sex on their wives, and a fifth of the women admitted to having experienced it. Also, 75 per cent of the men expected their partners to agree to sex. While Odisha and Uttar Pradesh had the highest incidence of intimate partner violence at 75 per cent, Punjab and Haryana followed at 43 per cent, and Maharashtra at 37 per cent.

Most domestic violence cases include sexual violence. Jagori, an NGO in Delhi, gets about 1,500 cases a year, and around 70 per cent of these pertain to domestic violence. About 90 per cent of the domestic violence cases involve marital rape. “When we interact with these women, they gradually open up about having faced sexual violence, too,” said Chaitali, a coordinator at Jagori. A much larger number would be going through it silently. “There are many social pressures on the woman. She is afraid that if she says no she will be beaten up, or the husband will stop giving money or go to another woman,” said Chaitali.

Marital rape is still a taboo subject for the woman to broach. Many women who seek help do not want to register a complaint. Recently, an NGO in Lucknow came across the case of a woman whose husband inserted a screwdriver into her vagina. “But the woman did not want to register a case. She said she had two children and nowhere to go,” said Apoorva Srivastava of the Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives.

Colin Gonsalves | Aayush Goel

Colin Gonsalves | Aayush Goel

Sangeeta Rana, a Delhiite who approached the Human Rights Law Network for help, had been married for seven years. She said she had been reduced to a sex slave. “He comes home drunk and starts shouting at me and beats me up if I say no to sex. He has forced me into having anal sex also,” said Sangeeta. The man would spit the gutka he was chewing into her mouth to torture her. However, lodging a police case was not an option as she and her two children were dependent on the man.

There are cases where the husband had not spared the wife even when she was pregnant, or forced sex on her during menstruation or when she was unwell. The case of a man accused of sodomising his pregnant wife came to Additional Sessions Judge Kamini Lau’s court in Delhi in 2016. The man allegedly boasted about his act in front of his nine-year-old son. Lau rejected the man’s bail plea, invoking Section 377, even as the wife, heavily pregnant, came to the court and pleaded for his release saying she was in a state of destitution. Lau said she understood that the woman was under pressure from her in-laws.

It can get extremely brutal. The case of a woman who was forced into having sex just three days after a caesarean prompted the RIT Foundation to petition the Delhi High Court.

Marital rape has much to with expression of the man’s dominance over his wife, to show the woman her place or punish her. Relationship expert Rajan Bhonsle said most husbands believed that their wives could not refuse sex. “The social conditioning is such that the man cannot take ‘no’ for an answer, while women are taught not to say ‘no’,” he said. According to him, marital rape is more traumatic than stranger rape. “The woman goes through it every day for years. She cannot complain and there is no escape,” he said.

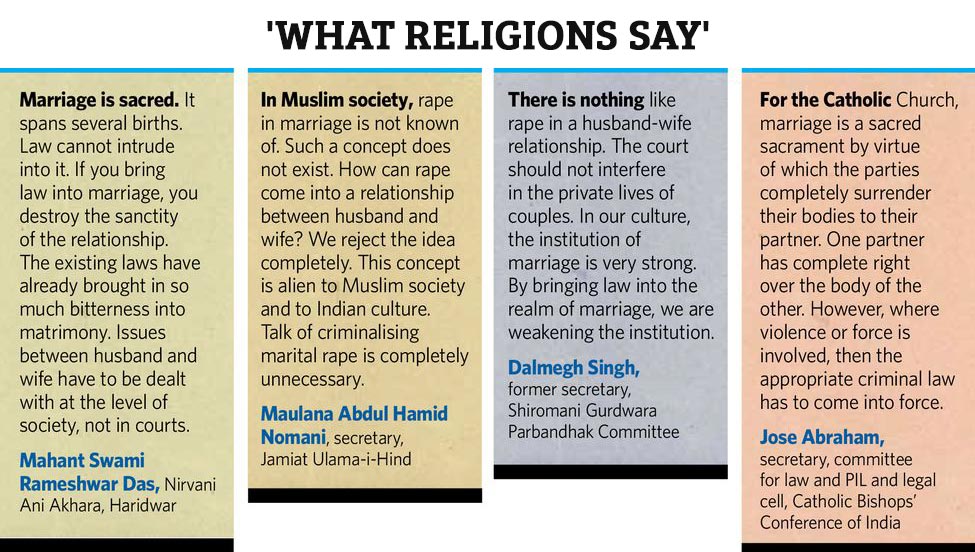

The government’s affidavit in the case states that criminalisation of marital rape “may destabilise the institution of marriage apart from being an easy tool for harassing their husbands.” Even the last government, despite its assurances, did not implement the Justice J.S. Verma Committee recommendation to strike down the exception.

Former Mizoram governor Swaraj Kaushal was among those who opposed criminalisation of marital rape. “There will be more husbands in the jail, than in the house,” he tweeted. “There is nothing like marital rape. Our homes should not become police stations.”

Mariam Dhwale of AIDWA said the opposition reflected a patriarchal mindset. “Crimes against women are seen as acceptable. And, any law meant for protection of women has come after a long struggle,” she said.

Rebutting the argument that marriages would be destabilised, Supreme Court lawyer Karuna Nundy asked, “Does rape destabilise the institution of marriage or a complaint of rape? What concept of marriage is the government protecting—that which by law includes rape?” Nundy appears for AIDWA and RIT Foundation in the marital rape petition in the high court.

Some of the opposition to a change in law is based on the belief that it will not help women any better than the existing laws do. Union Minister for Women and Child Development Maneka Gandhi had said that women should file complaints under the existing laws. Women’s rights lawyer Flavia Agnes said she did not believe in placing rape on a pedestal above the other crimes within marriage. “For a woman who is facing domestic violence, it is equally violating if her skull is fractured, her spine is broken, her cornea damaged or liver is injured or her vagina is penetrated forcefully,” she said.

Since marital rape is dealt with under the Domestic Violence Act, a question asked is in what form it would be included in the IPC. “Marital rape being part of domestic violence, and since there is an independent legislation on domestic violence, a moot question that arises is how a definition of marital rape will be carved into the IPC,” said Shantaram Naik, former chairman of the Parliamentary Committee on Law and Justice. He said the issue could be discussed only on the basis of a draft legislation that defines marital rape under the IPC.

Another crucial issue is proving marital rape in the court. The government’s affidavit asks what evidences the courts will rely upon “as there can be no lasting evidence in case of sexual acts between a man and his own wife.”

Lawyers, however, say evidence can be found in the form of signs of struggle, broken objects, or the woman’s screams that have been heard. The examination of the evidence in court is gruelling and ruthless. “The woman’s testimony has to be clear, consistent and convincing. In the end, the judge should not have any reasonable doubt with her testimony,” said Gonsalves.

There is a concern that if marital rape is criminalised, it will be misused by women to harass their husbands. “The exception is meant as safeguard against misuse. Law cannot be made for one person or a few persons if a greater number might misuse it,” said Niladri Shekhar Das of Save Indian Family Foundation, an NGO campaigning for men’s rights. This is, however, countered by the argument that there are many other laws that are misused, but nobody asks for them to be repealed. “Even if one woman wants to make use of the rape laws to bring her abusive husband to book, she should have the backing of law,” said Olivia Bang of the Human Rights Law Network.

The time has come for a legal decision on whether non-inclusion of marital rape in the rape laws is indeed unconstitutional. However, there can be no easy resolution, given the complex social and cultural

realities.

Some names have been changed to protect identity.