Shrimaan Mani Shankar Aiyar. Emne kahyu ke Modi neech jaati no che [Mr Mani Shankar Aiyar said Modi is of low caste],” declared Narendra Modi in the run-up to the assembly elections in Gujarat. Wasn’t it an insult to Gujarat, the prime minister asked at a rally in Surat. For good measure, he accused Pakistan of trying to interfere in the polls, and suggested that a former director-general of the Pak army wanted Congress veteran Ahmed Patel as chief minister.

The Congress quickly suspended Aiyar, but the damage had already been done. Modi had appealed to the Gujarati asmita. An insult to him was an insult to Gujarat as well.

Modi is adept at making emotional appeals. In the run-up to the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, he had spun electoral gold out of Aiyar’s chaiwalla jibe at him. This time, too, his rhetoric saved the BJP, which had been battling anti-incumbency, a rejuvenated Congress, ill-effects of implementing demonetisation and the Goods and Services Tax, and the challenges posed by the ‘caste triad’—Hardik Patel of the Patidars, Jignesh Mevani representing dalits, and Alpesh Thakore, who had the support of Other Backward Classes.

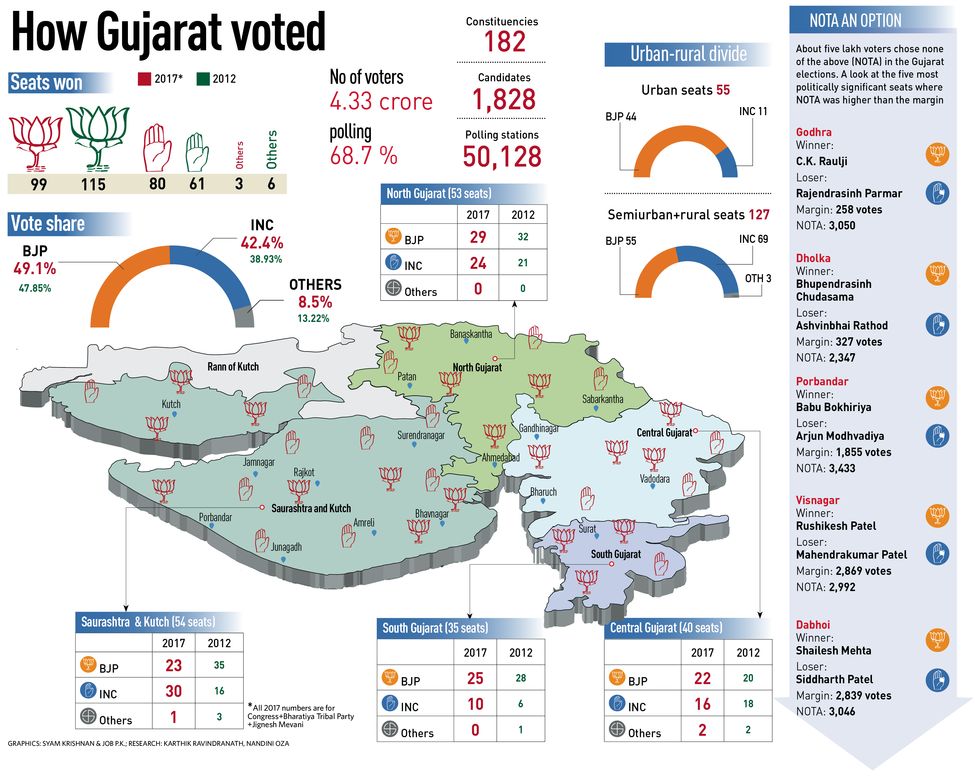

Modi powered the BJP to its sixth consecutive victory in Gujarat. But the final tally—99 seats for the BJP, 77 for the Congress and six for others—does not reflect how close the fight was. Or, what would have happened had Modi not addressed more than 30 rallies in the state.

Asked about what he thought of that scenario, Chief Minister Vijay Rupani told THE WEEK: “I cannot forecast the future.” He said it was a given that Modi would address public meetings, as he was the party’s tallest leader. Rahul Gandhi, too, had done the same thing for the Congress, he pointed out.

A senior BJP leader from Vadodara was more frank. “Had it not been for Modi,” he said, “we would not have got even 50 seats.” A day before the results were out, said the leader, he had expected the party to win 105 seats. “It appears that anti-incumbency was the reason for the BJP getting fewer seats,” said BJP spokesperson Yamal Vyas. “Modi helped lower further losses.”

But, unlike in previous elections, Modi and the BJP did not have much room to experiment with candidates. In the 2005 municipal corporation elections, for instance, Modi had denied tickets to most incumbent corporators. Still the BJP won easily. This time around, though, the party was forced to field candidates who were considered safe bets.

Also, the list of candidates for the second phase of the polls was announced at the eleventh hour—something which the BJP had routinely criticised the Congress for in previous elections. There was so much uncertainty over selection of candidates that BJP president Amit Shah, who had been camping in Gujarat since Diwali, had to personally inform some aspirants that they would not be getting the tickets they were promised earlier.

There were no state leaders who could shoulder the campaign on their own, so the BJP banked heavily on Modi and Shah. Rupani’s post-results statement was revealing: he thanked Modi for the campaign and Shah for the strategy.

It was Modi, however, who really swung the elections in the BJP’s favour. Many within the BJP say Shah does not enjoy as much respect from party cadres as the prime minister does. According to them, people voted for the BJP for the simple reason that they did not wish to see Modi in trouble at the national level. In some cases, they did not even care who the BJP’s candidate was.

This explains why the BJP was able to win 15 of 16 constituencies in Surat, a diamond and textiles hub where Hardik’s rallies had attracted huge crowds. “Yes, this city was hit badly by demonetisation and GST,” said a BJP leader. “Still, the electorate ignored their woes and chose Modi.”

For the Congress, MSP did what GST could not. In Saurashtra, farmers who did not receive the minimum support price for their produce helped the Congress fare exceptionally well. The Patel factor, too, worked in the party’s favour.

Rahul’s sustained campaign highlighting Gujarat’s lopsided development yielded good results in the tribal belt, too. But it did not make much of an impact in south, central and north Gujarat, from where Modi and Deputy Chief Minister Nitin Patel hail.

Much like the BJP, the Congress did not have capable state-level leaders who could capitalise on Rahul’s efforts. Shaktisinh Gohil, Arjun Modhwadia, Siddharth Patel and Tushar Chaudhary did try their best, but they all ended up losing elections.

With the absence of its stalwarts in the assembly, the Congress may shift its focus to young leaders like Thakore and Paresh Dhanani, who retained Amreli with a comfortable margin. A Patidar, Dhanani may become leader of the opposition in the assembly.

Talk is that the BJP will appoint a new chief minister to take on the stronger opposition. Among the names doing the rounds are that of Union Minister Parshottam Rupala and Karnataka Governor Vajubhai Vala, an OBC leader and former assembly speaker. That the BJP fell way off its original target of winning more than 150 seats has put Rupani on the defensive. “Yes, we did set a target of 150-plus,” he said. “However, it is not bad to get even these many seats after 22 years in power.”