It is amusing to read that India’s oldest political party hopes to revive its fortunes in the country’s politically most important state with the help of a public health expert turned political consultant. Hats off, though, to Prashant Kishor for successfully marketing his own brand and convincing Rahul Gandhi that he can do for the Nehru-Gandhi family scion what he did for the chaiwallah of Gujarat.

Let’s get some facts right. Narendra Modi led his party to victory in the general elections of 2014 partly riding a wave of resentment against the second United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government (2009-2014) and partly on the wings of hope that he could take all of India to Gujarat’s level of economic development. The 2014 verdict was as much a negative vote against UPA-2 as it was a positive vote for Modi.

In the assembly elections in Bihar, caste arithmetic and the logic of what the communists call “all-in-one” unity, dubbed the Mahagatbandhan, worked. You did not need spin doctors and strategists to deliver either victory. Yet, the politically innocent Rahul Gandhi seems to have convinced himself that a strategist can do for him what he cannot do for his party.

Elections are won by political leaders who stand upfront and offer hope, first to their own cadres and then to their electorate. Of course, leadership alone cannot deliver electoral victory. Leaders need cadres and a party organisation. The problem for Rahul Gandhi in Uttar Pradesh is that the Congress is bereft of cadres and organisation and that cannot be compensated by clever marketing strategy.

Illustration: Bhaskaran

Illustration: Bhaskaran

This is not a new experience for the Congress. Few remember that by the end of the 1980s the Congress was in dire straits and severely dispirited. Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi had been assassinated. The Bharatiya Janata Party was on the upswing, and so were a clutch of regional parties.

In that hour of gloom and distress the party opted for a leader who had no charisma at all. No one then imagined that the uncharismatic and low profile P.V. Narasimha Rao would be able to revive hope within the party and keep it in power for a full term. Yet he did.

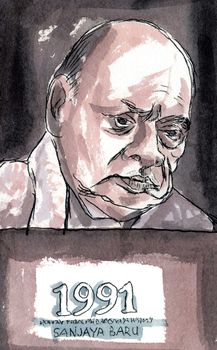

I have argued in my recently published book, 1991: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Made History (Aleph Book Co.), that Narasimha Rao’s decision to conduct organisational elections in the winter of 1991-92 and empower regional leaders within the party was a masterstroke that kept hope alive and the Congress together. The Tirupati session of the All India Congress Committee was an important milestone in the Congress finding life beyond the Nehru-Gandhi family.

It is a different matter that internal jealousies, power struggles and the desperate desire of the 'Nehru-Gandhi Lutyens Darbar' to regain their declining influence within the party and the corridors of power created conditions in which the party began to lose momentum.

One important lesson from 1991 is that a political leader can revive the spirits of a depressed, even moribund, political party by turning a crisis into an opportunity. Rao was quick to grasp that the economic crisis of 1991 was in fact a political opportunity not just for himself but also for his party.

It was not just the economy that was in crisis but India’s foreign policy was caught in a cul-de-sac, with the implosion of the Soviet Union. The world had become a more difficult place for India with its sole ally gone. In that dark hour, Narasimha Rao offered leadership of a kind that made the Congress and the country look to the future with hope.

If there is a lesson to be learnt from the experience of 1991 for the future of the Congress in 2016, it is that the party needs a leadership that is seen as offering hope in the future. Rahul Gandhi has so far failed to emerge as the leader of hope, nor has he been lucky enough to locate a crisis that can be turned into an opportunity.

editor@theweek.in