The Bollywood blockbuster Dirty Picture starring Vidya Balan as Silk (Smitha) in a career defining role, had a famous dialogue where Silk described films as merely “Entertainment, entertainment, entertainment”. And, for a very large part of the last decade trade insiders have pointed to box office collections of Bollywood masala entertainers and declared smugly that only entertainment works.

Art, however, and cinema, particularly, has far greater potential. Like literature, good cinema, too, has the power to transform mindsets and attitudes and thus effect (perhaps slowly) a larger social transformation. Sensitive storytelling can make audiences more empathetic and insensitive, tone deaf or propaganda films can inflame the existing fault-lines in society and normalise bullying or hate.

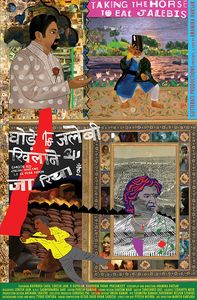

Recently, audiences were reminded of this highest purpose of cinematic art by a small, self-financed, self-released, unapologetically avant-garde, almost defiant, totally independent Hindi language film—Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (I’m Taking The Horse To Eat Dessert) written and directed by veteran theatre director Anamika Haksar.

Based on extensive research and a questionnaire based study of the dreams and fears of the street folk of Old Delhi—loaders, pickpockets, daily wage labourers, small scale factory workers, garbage pickers, street vendors, street singers, beggars, and homeless people, the partly fictionalised tale follows three friends who live and earn from the streets and narrow alleyways of Old Delhi. Patru, a pickpocket; Laali, a communist loader; and Chhadami, a street vendor, are roommates. We peak into their lives hidden in the shadows of the ruins of the once glorious Shahjahanabad. We leap into the dreams of the labouring people of this world using montages of moving images, VFX, folk art, graphic design, folktales, local legends, music, dialogue, dialect and sound design. The film is part metaphor, part allegory, part installation, part ballad and a heartfelt ode to the people we un-see everyday. An omnipresent but unseen world—that makes it to the news and national consciousness only as statistics of those fleeing the capital on foot during a pandemic—is granted individuality and ‘the lead role’, as we say in film parlance, by Haksar.

The film is unyielding like its maker. It challenges us intellectually while disturbing our collective ennui, used as we are to watching glossier, more palatable content even if it is violent. ‘Ghode Ko..’ doesn’t sweeten its world. The opening shot is a languorous camera pan over a gutter, later we see an extreme close up shot of the trembling muscles of a bare bodied loader. Haksar’s deft symbolism reminding us of the rat-like existence of these people valued only a little more than load-bearing cattle. Known to push the boundaries of ‘form’ in her theatre work, Haksar experiments with the cinematic form, opening up the storytelling to include in one place Madhubani folk art inspired graphics! Though non-linear with a generous dollop of magic-realism; the film is loaded with multiple meanings and layers. It is a film scholars’ delight, but will equally stir sensitivity in a lay audience! Haksar adds ideology and activism to her craft by imbuing these normally marginalised people with not just protagonist parts, but dignity, depth, and often a quiet heroism. Haksar treats gender with an unblinking matter-of-factness. I wondered where the women were and almost halfway through the film when the first women were seen, scavenging through garbage in a land-fill, I realised with a mental jolt that Haksar is pointing out that in society, and in the labour market women exist at the margins.

It is rewarding then to see this tiny, brave film run to 80 per cent occupancy in Delhi and Mumbai, adding a second and maybe third week to its run, with more cities and more shows!

Bollywood is a scared industry these days, playing safe in every which way they can. Perhaps, it could take a lesson from this unsupported, unabashed, un-fearing film and remind itself that storytelling has transformative power! You walk out of the film feeling stirred and oddly empowered. Thank you, Anamika ma’am, for bringing the narrative back to the labouring hands whose sweat fuels our comfortable lives and routines.

The writer is an award-winning Bollywood actor and sometime writer and social commentator.