While there is as yet no conclusive evidence, apart from what former Prime Minister I.K. Gujral has recorded in his autobiography, Matters of Discretion, it is possible to conjecture that in April 1999 Congress president Sonia Gandhi did fancy the idea of heading a coalition government in New Delhi. “We have 272 and we hope to get more,” Sonia told the media as she walked out of the Rashtrapati Bhavan after meeting President K.R. Narayanan.

Samajwadi Party leader Mulayam Singh Yadav nipped the bid in the bud by refusing to join the venture. Gujral records that it was not just Mulayam but also Harkishan Singh Surjeet, general secretary of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), who made it clear to him that the Left would not support a Sonia-led coalition. It was an April that robbed the spring in Sonia’s step.

Over the next five years, Sonia dumped all her past prejudices and worked assiduously to win over a clutch of regional parties, including a party that she and people close to her had accused of conspiring in her husband’s assassination. The Jain Commission enquiry into Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, in which critical remarks had been made about the DMK, were framed and hung on the walls of the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation’s Jawahar Bhavan building in the heart of Lutyens Delhi. By 2004, Sonia had not only reached out to the DMK, but stitched up support from the Left and from the Congress rebel Sharad Pawar to become chairperson of the United Progressive Alliance.

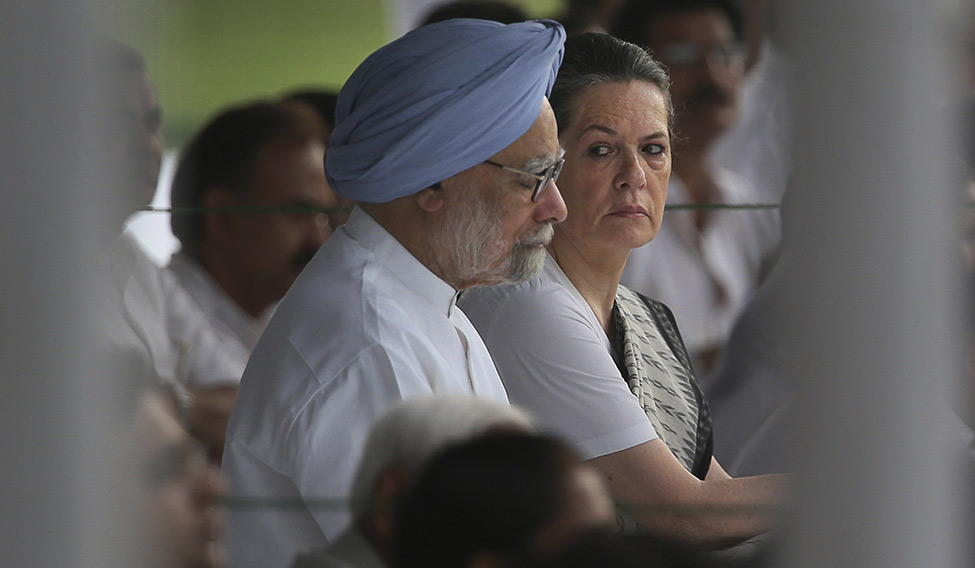

The Congress Parliamentary Party then made a curious departure from standard practice, as journalist Harish Khare reported in The Hindu (May 20, 2004), when it chose to elect Sonia as its ‘chairperson’ and then allowed her, in turn, to “nominate” Dr Manmohan Singh as the head of government. Parliamentary practice till then was that the leader of the CPP became the prime minister. The so-called ‘dual’ power arrangement that was thus ushered in had a purpose that became explicit as the UPA’s term progressed—to facilitate the political rise of the next generation of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. While the April 1999 faux pas may suggest that Sonia nursed an ambition to become prime minister, the historical verdict may finally well be that she saw her role as that of a Queen Regent, holding fort till her son was ready for dynastic succession.

Whatever Sonia’s flaws and frailties, few will question the fact that she has played that role of a ‘regent’ to perfection. In the end, her legacy would be that she did keep the flame of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty burning. If a member of that family does not ever return to power in New Delhi it will not be because Sonia did not try. She has done her part, splendidly. Her mother-in-law and her husband would have felt proud to see the manner in which Sonia kept the Congress flag flying. In the end, if the party becomes history, no one will blame her for not doing her bit. She will, however, be blamed for not understanding in time that the time of the dynasty is over. Her insistent projection of Rahul Gandhi, and the Congress’s pusillanimous response to this maternal obsession, have brought her party to its present sorry pass.

Even after more than 30 years in public life, first as a prime minister’s spouse and then as leader of the Congress, Sonia remains an enigma to most political analysts.

There is no doubt that she is a woman of tremendous grit and determination, and is very focused. Her life thus far is a sum of opposites—power, pelf, wealth, comfort, victory, loneliness, tragedy and failure. She has shown enormous courage as a woman, spouse and mother. She has demonstrated great cunning as a politician. She is imperious and reserved, yet warm and gregarious. She has provided leadership for some truly progressive social and economic initiatives that the UPA took and that Prime Minister Narendra Modi has taken forward. She has also allowed widespread corruption to flourish with many Congress leaders imagining that it was all right to make money when in government as long as some part of it was also passed on to the party. Sonia’s legacy, therefore, will be a mixed bag.

Sonia’s political evolution, from being a housewife to becoming a Queen Regent, is testimony to her courage, grit and cunning. Even those very close to her in the period 1998 to 2004 did not think she was capable of achieving what she did. Some of them viewed her as lacking in adequate education to understand a complex society and nation like India. She was thought of as a socialite interested in the good things of life. Her leadership of the UPA forced many around her to change their opinion. Clearly, she had evolved politically and intellectually.

However, it is not uncommon that even the most carefully cultivated political persona errs on occasion to reveal an inner self. Many in the Congress were deeply offended by the manner in which she dealt with Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy’s widow. It revealed a side of her personality that P.V. Narasimha Rao agonised about in his conversations with Natwar Singh. It reminded them of Rajiv Gandhi’s treatment of Andhra Pradesh chief minister T. Anjaiah. She may have been chairperson of the National Advisory Council, with its membership of the liberal-progressives, but in the end she was and is, after all, Queen Regent.

Dr Sanjaya Baru is a writer, policy analyst, distinguished fellow at the United Service Institution of India and secretary general, FICCI.