It is just past 1pm. The afternoon sun is settling into its mellow phase. Students sit on wooden benches in the pink-walled dining room of the Centre for Social Responsibility and Leadership (CSRL) in Delhi. They are talking more than eating—enjoying their brief break from studies.

For 11 months every year, nearly 40 children in this residential coaching centre study for hours every day to crack the Joint Entrance Examination to IITs, one of India’s toughest exams. “Thirty of 39 students are first-generation learners,” says senior centre manager Meenakshi Shahi.

This is the sixth batch she has mentored. Shahi has many stories of children having defied their circumstances to turn their lives around by sheer dint of hard work, determination and the E word that has been costing us over 2 per cent on everything—education.

Pictures of children, smiling formally at the camera, abound. Shahi, her eyes glowing, rattles off their stories: Poonam Gupta, daughter of a panwalla, is studying at IIT Kharagpur; Arjun, whose parents are tailors, is studying at IIT Rourkee.

It is not a revolution yet. But, to borrow a line from a Scorpions song, it is the wind of change. In 2014, as many as 30 per cent new engineering students in Tamil Nadu were first-generation learners. Most of them remain faceless, lost in the statistics that are trotted out at various forums to prove that India is indeed the country of the future. “The ripple effect of 50 years of Constitutional democracy and 25 years of liberalisation has started now,” says Meera Mitra, author of Breaking Through: India’s Stories of Beating the Odds on Poverty. “We have official as well as other data to say that people are coming out of poverty: 137 million people between 2005 and 2011, whatever method you use.”

These people have stories of indomitable spirit and conquered poverty to tell. Theirs are the faces behind the statistics of the India growth story. A quarter of a century after the economic liberalisation, their lives will be on what Manmohan Singh will be judged for.

Sher Mohammad is the poster boy of this India of possibilities. His father sells fruit at a busy intersection on Lodhi Road in Delhi. Sher studied at CSRL and enrolled at IIT Delhi. He now works at Oracle in Hyderabad. “We need jobs in crores. Companies like the one I am working in can only provide 10,000 jobs. If we want real change, you have to propagate it at the root. It has to be a change that has impact on every level,” he says.

For people like Sher, it is a herculean task to climb the social ladder. “We have looked at the poor as a passive lot,” says Mitra. “There is an active engagement; there is an aspiration component. It happens especially in metropolitan areas. We must pay attention to these examples to see what the roadblocks are, what their travails are. It is where our interventions should be.”

Many ordinary Indians have extraordinary stories of struggles to tell. Take Sarath Babu, for instance. Son of an idli vendor in Chennai, he got into IIM Ahmedabad. He graduated and went back to the slums he grew up in to start a food business for his mother. And he still lives there.

Take Mohit, who works at Deloitte, a multinational professional services firm. He grew up in a small house in Old Delhi and rarely stepped outside his home, because his parents did not want him mingling with bad company. His father fixed computers. “The original Iron Man’’ is how Mohit describes his father.

Today, Mohit owns a car. Articulate, witty and filled with a sense of purpose, Mohit swears by hard work. “There are many ambitious people. But they have not been fortunate enough to make the change. I have grabbed every opportunity and made the best of it. I never waited for it to knock again,” he says.

If there is one thing that distinguishes first-generation learners from middle-class aspiring Indians, it is the readiness to work hard. “There is an idea that if you are talented, you can move,” says social commentator Santosh Desai. “There are cases of people from small towns who have made it grand elsewhere. This is the first generation [of learners]. And they haven’t really framed their expectations, which is why there is no anger, no bitterness. Unlike the middle class, which has fixed ideas of college or school, this is the first generation and it is generally an experience of possibility rather than expectation.”

Amin Sheik | Amey Mansabdar

Amin Sheik | Amey Mansabdar

Amin Sheik

Mumbai's Oliver Twist

Amin Sheikh is Oliver Twist. His journey—from the streets to an orphanage to becoming the owner of a cab company—is proof that, in Mumbai, miracles are possible. “I first ran away from home when I was five,” he says. “My father was an alcoholic.” He worked at a teashop where, after working for eight hours, he would be paid $2. “The owner used to hit me,” he says. “One day, I was running with glasses in my hand. I fell down and broke them all. I was so terrified that I ran away.”

He ran till he reached Malad station. “There I saw children walking around and eating out of the garbage [bin]. I thought I could survive there,” he says. “People would come and do things to me. I was too young to protest. I didn’t know what was happening.”

He polished shoes, fought off starvation and eventually went back home, only to run away again. “One day, Sister Seraphine found me on the station,” he says. She took him to Snehasadan, an orphanage that became his true home. Today, his tiny, spotless flat is round the corner from the orphanage.

At school, he was an outsider and was picked on. But, he was a fast learner. And Snehasadan taught him a lot about life and love. It is this knowledge that drove him to work hard to find his place in the other Mumbai, the world he could only dream of. He sold newspapers and set up his own stall at 17.

Then came Eustace Fernandes, the artist who drew the 'Amul girl'. “He would take one boy [from Snehasadan] every year and train him,” says Sheikh. “I took every opportunity that came my way. I fought, I worked hard. If I hadn’t, I would still be a driver.” Sheikh became the artist's man Friday and did odd jobs.

But, like Oliver, Amin wanted more. “I asked him to take me with him to Barcelona [where he went every year]. He asked me ‘Are you mad?’ I went to my room and cried. I did understand. What would he tell his friends? That I have brought my driver with me? The next day, he came knocked on my door and gave me a card. There was a ticket in it,” he says with a smile.

Before going to Barcelona, Fernandes had given him a second-hand car and he had started his own cab company. Soon, business grew and he bought another car. He also wrote a book, Life is Life, which has sold thousands of copies.

“I now want to start this cafe where street children from Snehasadan will be able to get jobs,” he says. Amin, who ran away as a child, wants to equip them with the skills to run towards a dream instead.

Nisha & Tabassum | Aayush Goel

Nisha & Tabassum | Aayush Goel

Nisha & Tabassum

Bouncing back

Typhoid saved her. “My wedding was fixed when I was 14, but it had to be called off,” says Nisha, gleefully. The 29-year-old girl from Saharanpur, in Uttar Pradesh, escaped matrimony by falling sick and is now a bouncer at Hauz Khas Social, a cafe in Delhi.

She, along with her sister Tabassum, 27, represents countless young women from smaller towns who fight the diktats of patriarchy. “My father refused to let us study after Class VIII,” says Nisha. “There was no point in educating girls, he believed.” It was her mother who insisted that they be taught. “We would study in secret at night. Under the covers of a quilt with a flashlight or with candle light,” she says with a smile. “Once, the panchayat was called to stop us from going to school. The tension in the house was terrible. My mother had to face the brunt of my father’s anger. But, she refused to bow down.”

It is this indomitable spirit that the sisters inherited. “My eldest sister who had got married when she was a child was sent back home by her husband. So, he [father] realised that it was probably better to educate us,” she says with a laugh.

Nisha worked a lot of jobs, including with event management companies, before becoming a bouncer. Tabassum, her model-thin sister, is also a bouncer at a Noida pub and is the foil to Nisha’s exuberance. “I am strong. You don’t need to be fat to be strong,” she says.

Their journey from conservative Saharanpur to Delhi is typical of post-liberalised India, of migration, mobility and a growing economy. Their father had to move out to find better opportunities. Though he could not find a job, the girls became breadwinners. Now, the man who opposed their education depends on their income. The unusual nature of their job—a shattering of a stereotype—has made them equal, especially in the family. “Now my parents are proud,” says Nisha. “They don’t worry about us. Earlier, my mother would stay up at night waiting for us to come home. Now she knows her girls can look after themselves.”

Their dreams are modest, yet audacious. They are determined to change their lives and their family's. For two girls who weren't allowed to go to school, working in Delhi, that too at night, is hope. It is more satisfying than numbers will ever be. “Here, I feel free,” says Nisha, looking at the cafe spread out below. It is a freedom she has fought long and hard for.

Nitin Daksh | Aayush Goel

Nitin Daksh | Aayush Goel

Nitin Daksh

Balancing act

Nitin Daksh's life is a metaphor for India: it straddles two very different worlds. He is an engineer whose parents are illiterate. His day begins early: he starts from Gokulpuri, a forgotten corner on the outskirts of Delhi, and traverses the capital to reach Gurgaon, the city of dreams where he works at a software firm.

His father is an invalid who works as a courier when he is well enough. Despite the family’s hardships, Nitin’s mother was determined that her children go to school. “Even if it meant that they had to eat less, they would send their kids to school,’’ he says.

For over a decade, she sat bent over with a blade in hand, making slits in a sheet of stencilled paper to make stickers for pressure cookers. She would wake up at 6am, finish cooking meals and then measure her day in stickers of four inches. The work is gruelling, but it earned her Rs.40 a day.

It is this almost Dickensian world that he battled his way out of. Nitin, who was good at studying, went to the Pratibha Vikas Vidyalaya, run by the Delhi government for bright children. “I would come back from school and sit down to work with my mother,” he says. “It was how we spent our holidays.”

The work would start in the morning and go on till noon. “We would take a break for half an hour, have lunch and continue till dinner. We used to spend time sharing stories,” he says. “If you sit next to someone for 18 hours, you know everything there is to know about that person. It is what kept us bonded.”

When he enrolled in Delhi College of Engineering, he supplemented the family income by tutoring children. He could not afford to attend coaching classes for himself. “It [the fees] was over Rs.1 lakh,” he says. “I didn’t want to embarrass my parents by asking for something they couldn’t afford.”

He finally got into CSRL. “My friend suggested I take the entrance test. I did, cleared it and became part of the institute’s first batch,” he says.

Those days, when he came home to visit his mother, the boys in the neighbourhood would walk up to him and taunt him about studying to be an engineer. They wanted to remind him that he was overreaching himself. “Today, they hold me up as an example,” says Nitin with pride.

Vijay Kumar Majhi | Aayush Goel

Vijay Kumar Majhi | Aayush Goel

Vijay Kumar Majhi

Hard drive

Vijay Kumar Majhi is a software engineer. In a country that has become synonymous with techies, his choice of profession may not be remarkable. But his journey is.

His father is a plumber who refused to let his job define his son’s future. Vijay hails from an Odisha village where it is a huge achievement to be a postgraduate. As a student in a government school, he often walked around the neighbourhood to find anyone who could help him with homework. Those were the hard years. Yet, with his father to support him, he refused to bow down to circumstances.

“It is easier to send your children to work so that they can earn money. But my father decided that he would rather that I had a future,’’ he says.

Vijay studied hard and won a scholarship from the Delhi Commonwealth Women’s Association to study at Sri Venkateshwara College in Delhi. “Nothing beats hard work,’’ he says.

To earn additional income, he would often work as a labourer in the hot Delhi summer. “It is very difficult to do physical labour,” he says. “Only someone who has actually done it knows what it feels like. I am proud of that.”

The first time Vijay walked into his office in Noida, he got goosebumps. “I was super-excited,” he says. “It was a gigantic glass building, just like what you see in English movies.”

Now 26, Vijay has settled into his job. He hopes to get a promotion next year. For a boy who had to fight for what most children take for granted, the act of being able to buy a pair of branded jeans is as exhilarating as it is empowering. “When I was very young, I loved Pilot pens,’’ he says. “I wanted one. But my father refused to buy it for me, because it cost Rs.20. At that time, it hurt me.”

The hurt turned to respect when he realised that his father gave him the best chance to fulfil his dreams. At his office, he often talks about his father to let his colleagues know how far he has come. “I want him to retire next year,” says Vijay. “I will have earned enough money by then.”

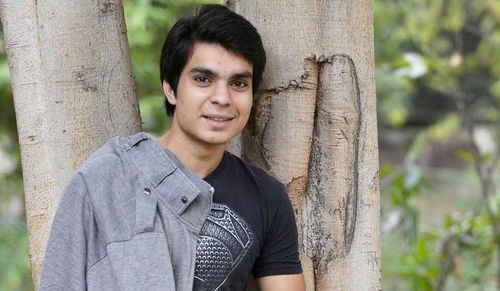

Shahzaad | Arvind Jain

Shahzaad | Arvind Jain

Shahzaad

Making his mark

The flyover neatly divides the two halves. On the one side is Nizammudin Basti, crammed with tiny houses and centuries-old buildings where privacy is an impossibility. On the other is the quiet, sprawling east side of Delhi, which has independent homes nestled in leafy gardens. The divide is more than just physical. It determines lives and lifestyles.

Shahzaad was born on the wrong side. Now, at 19, he has moved towards bridging the gap. He works at Marks & Spencer, a multinational retailer. Soft spoken, unfailingly polite, and dressed nattily in jeans and sweatshirt, Shahzaad epitomises the promise of the great Indian dream. When he was a child, his parents, who are barely literate, could not make ends meet. “I credit my mother for ensuring that I worked hard and studied,” he says.

As a child, he never stepped out of the Basti, except once to watch a movie in Saket. The modernity that India now prides itself on is still alien to him. “It is a clearly different world outside,’’ he says. “I have learnt so much after I started the job. We get shaped by the environment that we are in. The people I interact with at work are of a certain standard.”

For Shahzaad, the job at Marks & Spencer is more than just about earning money. It is his chance to get out of one of the densest ghettos in the city, breathe, broaden his horizon and dream. “The money has helped a lot. My salary of Rs.20,000 a month ensures that our lives change,” he says. “We had to scrape together to survive. Now I can buy my father a shirt from Marks & Spencer, which I did with my first salary. He loves it.”

Shahzaad has his eyes on a promotion as floor manager. “I think I will continue with retail,” he says. “I have to study more. If I had done my BA, I could have become supervisor in one year. Now, it will take two years.”

What he lacks in education, he makes up with grit, hard work and endless enthusiasm. “People want to get ahead. They want money and career growth. But they come only if you work hard. You need to fight to overcome every hurdle,” he says.

He learnt English and how to use computers at a centre run by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. It is there that he found out what it takes to walk over to the other side: confidence. “English is the future, so is computers. I didn’t have the confidence to talk. Now I do,’’ he says as he fiddles with his new smartphone to send a Facebook friend request to a photographer.

“I used to accept anyone who sent me a request,’’ he says. “Now I have over a 100 requests pending. I realised it was only for friends.”

The divide has just become a little less daunting.

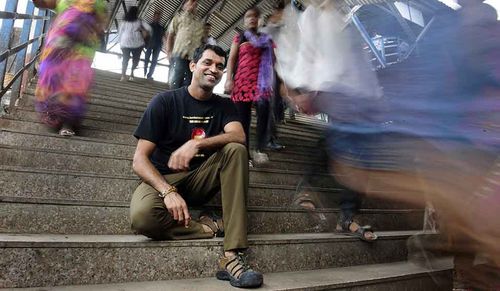

Sher Mohammad | K.R. Vinayan

Sher Mohammad | K.R. Vinayan

Sheer Mohammad

Fire in the belly

Pubs, fast food outlets and the Oberoi Trident are stacked up against each other in Hyderabad's Cyberabad, the city of a thousand cyber sweatshops. Sher Mohammad, 23, has been part of this sleepless industry for six months. He is the first person in his family to hold an “office job”. He is certainly the first IIT graduate in his area in Delhi.

His father sells fruit off a pushcart in Kotla Mubarakpur, a sprawling urban village in Delhi's heart of darkness, where most boys drop out before middle school. Tiny streets are crammed with print shops and shops selling bathroom fittings. Childhood is an extravagance here. In school, Mohammad had never read a book other than textbooks.

“We were a class of 40,” he says. “Only ten finished school. Weaker students just fell by the wayside. Neither the school nor society motivated them. They do not have hopes. They do not have money. They do not feel they have a future.”

A combination of factors saved Mohammad.“I was a topper in school,” he says. The Delhi government had launched a scheme to pick the brightest kids from government schools and put them in a special school. That was the turning point. “There is no substitute for hard work,” he says. “In IITs, each student is a topper. It motivates you to work harder.”

The first one in his family to be educated, Mohammad is a firm believer in the power of education. “By the time they turn 13, kids end up working with their parents. The parents see them as earning members. They cannot think beyond survival. How do you expect a child to motivate himself then?”

For a young boy whose life has been dominated by poverty, Mohammad has a rather philosophical view of money. “Money is not that important,” he says. “It buys things, that's all.” Most of his first salary lies untouched. "I don't need anything,” he says. “I gave my parents a lakh of rupees.”

When Mohammad was in IIT Delhi, the Aam Aadmi Party was collecting data to come up with a different model for education. He helped the AAP with its surveys. His average day was from 7am to 2am. Have things changed? “The infrastructure in government schools has improved,” he says. “But, the level of education is the same.”

Syeda Fatima | K.R. Vinayan

Syeda Fatima | K.R. Vinayan

Syeda Fatima

Target cockpit

It’s Monday afternoon, and old Hyderabad is shaking off its drowsiness. Burqa-clad women and men in skull caps throng the bazaar. Displays of bright, bejewelled bangles blind passersby. Kabab-wallahs and fig-laden rickshaws zigzag through busy roads.

Syeda Fatima lives on the edge of this claustrophobic, lively and buzzing quarter. Her daughter, six-month-old Mariyam Fatima, has just dozed off. At a glance, Syeda fits perfectly into the stereotype of a conservative Hyderabadi Muslim woman. She married at 24, had a baby in a year and lives with her in-laws. But, she defies these neatly-ticked boxes with her profession—she's a pilot.

The symbolism of a hijab-wearing pilot speaks for itself. But, it is more than just about breaking a stereotype. Her father, Syed Ashfaq Ali, works in a bakery; her mother is a homemaker. In an area where one in two women is educated, dreaming of flying planes was a fantasy. “I was in Class IX when I read in a newspaper that there were very few women pilots. There was not a single one from my community [in Hyderabad],” Syeda says, looking at her fingernails, painted bright blue. “I wanted to be different.”

But, money was always an obstacle. Her school principal helped her with the school fees. The financial crunch became severe when her father quit his job in Saudi Arabia, after being injured at work. But, Syeda was determined, and studied like she was possessed. “She used to stay awake till 5am,” her father says, beaming.

After school, she tutored schoolchildren to earn extra money and prepared for entrance examinations. But, there was no money for flying lessons. Her parents suggested that she become an engineer, as full scholarships were available. But, help came from Zahid Ali Khan, editor of Urdu daily Siasat. Says Syeda, “At a function, I said that I wanted to be a pilot. He was impressed and helped finance my commercial pilot licence. Since then, he has been my adopted father.”

Post-marriage, her husband and in-laws have solidly backed her dream. On September 6, 2013, she took to the skies for the first time. After getting the licence, she needed to train for specific aircraft. The fees? Around Rs 30 lakh. Her husband, an engineer, encouraged her to write to ministers for help. “I know it will not be easy,” he says, bouncing Mariyam on his lap. “I do not expect it to be. I now have more responsibility—the baby and her.” On International Women's Day, Telangana Chief Minister K. Chandrasekhar Rao cleared funding for her training.

Syeda's mother-in-law, who was a teacher for 34 years, says, “My father used to say, 'If you educate a woman, you have educated a family. If you educate a man, you ensure he gets a better job.'” Her criteria for the wives of her sons were simple: “Education and good manners.” Fatima—tiny, soft spoken and with a big smile—fits the bill and a little more.

Parthiban Ayyappan | R.G. Sasthaa

Parthiban Ayyappan | R.G. Sasthaa

Parthiban Ayyappan

Cleaner to coach

Clad in a blue T-shirt and black trousers, Parthiban Ayyappan sits in a plastic chair behind the glass wall of the squash court in Bhavan’s school, Chennai. Parthi, as he is popularly known, keeps his arms behind his head as he watches seven small boys rally, hitting the ball back and forth inside the glass court.

“All my life, I wanted to hit that ball, teach budding players and train them to be champions,” says the 27-year-old, who has won seven national titles as a professional coach.

Squash has helped this school dropout, who started 20 years ago as a cleaning boy at the Madras Cricket Club. He has travelled around the world, playing squash for the country, winning several national and international titles and is now a hero for the 60 children he coaches today.

The first person to go to school from his family, Parthi was keen on his studies. But financial constraints forced him to quit school and help his uncle who was a cleaner at the Madras Cricket Club. Each day, he would stand in a corner of the squash court at the club and watch members play. Once they left, Parthi would walk inside the glass court barefoot and copy their shots with a ball and a racket left behind by them.

Although his uncle discouraged him, Parthi continued with his practice, hitting the ball hard, higher and higher against the wall. Things started to change in 2002, when Major Maniam, consultant coach of the Squash Rackets Federation of India, noticed the spark in Parthi and asked him to play along with club members. He soon got popular coach Cyrus Poncha to train him.

“For me, a school dropout from a poor background, it was a challenge,” he says. He still remembers his first tournament. He was the runner up in the under-17 section of the Complan Cup in Mumbai in 2002. He also reached the semifinals of an all-India under-17 tournament at the Bombay Gymkhana Club and another tournament at the Cricket Club of India the same year. He also took part in the world junior championship in Chennai in 2003 and the world junior championship in Pakistan in 2004.

Parthi remembers the time he went for his first international tournament. It was in Hong Kong in 2002, and he did not talk to anyone other than his friends from Chennai. But now, he is no longer worried about his English. Today, he speaks to his students, who are all financially well off, in English. “I love the game too much. It’s my passion, my profession, and an outlet to express my desire.”

WITH LAKSHMI SUBRAMANIAN