Farmer Jaspal Singh did not think much of it when he spotted the grass trampled on his farm in the border village of Bamiyal in Punjab on the cold morning of January 1. The farm bordered a small rivulet, originally an irrigation canal, that flowed through the barbed-wire fence that stood a few metres from his farm on the International Border with Pakistan. He did not report it to anyone; either he did not think much of a few village folk walking across his farm, or he knew it was wiser to keep quiet about the drug pushers.

Smugglers have been using small openings on the border fence—like the spot through which the canal flowed into Pakistan—and in some places they had even dug tunnels under the fence through which they have been pushing narcotic drugs into India and pharmaceutical drugs from the Indian side into Pakistan. Often the Border Security Force and the constabulary in the local police stations knew of these spots, and of the operations, but looked the other way. For, the drug pushers had their uses. Often, they provided vital information about happenings on the other side, and some of them were the Intelligence Bureau’s double agents.

The drug men also had a strict code of honour: that there would be no killing and no help to terrorists. The code had been there since the 1980s, at the height of militancy in Punjab, when the drug men provided plenty of dope to the Punjab Police to nab and kill Khalistani insurgents.

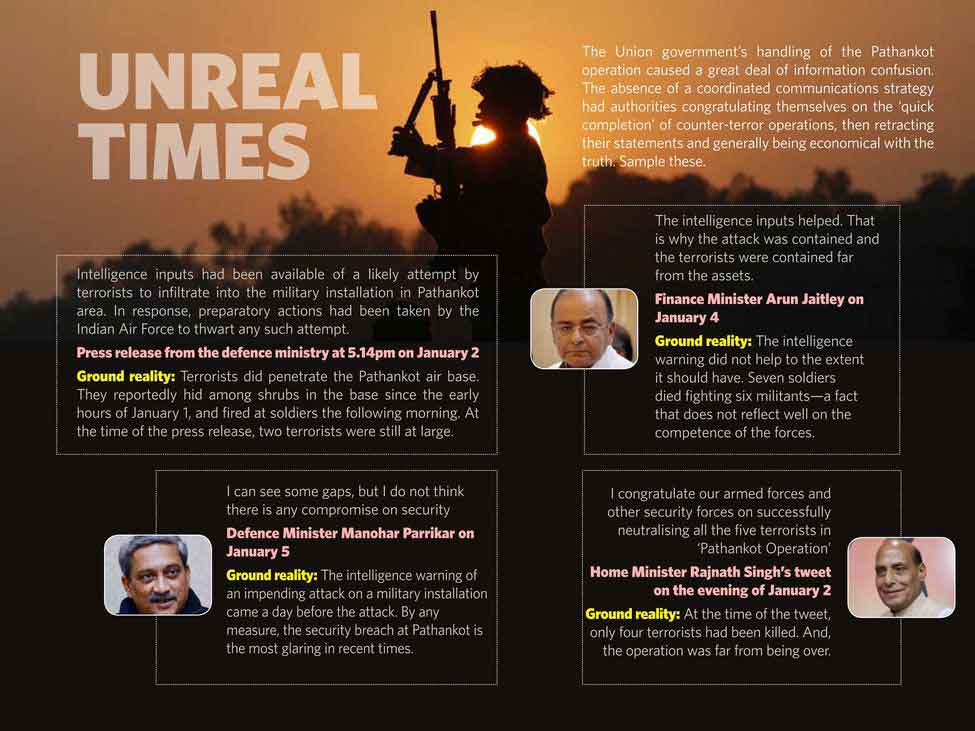

Now, the same explanation is being offered by intelligence men about the strange behaviour of the Gurdaspur Superintendent of Police Salwinder Singh. At around 2.45am, Kuldip Singh, chief of the Pathankot Rural Police, received a phone call from Salwinder Singh saying that his blue-beaconed Mahindra XUV had been waylaid while he was driving from Pir Baba dargah at Narot Jaimal Singh, that he and his cook Madan had been let off on the way, that his jeweller friend Rajesh Verma had been injured and dumped somewhere on the road, and that their three cellphones (his two, and Verma’s one) had been taken away by the carjackers. State police chief Suresh Arora was alerted, and he told Additional Director-General of Police H.S. Dhillon to rush to Pathankot. “By 7am, ADGP (law and order) was asked to reach Pathankot immediately,” Arora claimed later. The BSF was alerted and Deputy Inspector-General (Border Range) Vijay Pratap Singh immediately ordered a combing of the entire border. Yet, most policemen who heard the story did not take it seriously. Another drug-run, they thought. Maybe the SP, too, knew?

It was the accidental discovery of an Innova, with the body of its owner-driver Ikagar Singh, who worked as a cabby, that alerted the police. Ikagar’s family told the police that he had received a call to ferry someone to hospital at night and had left home. But the call record on his phone showed a Pakistani number! Even that could be explained as a drug link, but there was another factor that alerted the police to something more sinister than that. Among the no-nos in the code of honour among drug men was that there should be no killing. And here there was a body.

The game had gone wrong somewhere. The Centre was alerted. At 7.30pm, National Security Adviser Ajit Doval held a meeting with Army chief Gen Dalbir Singh Suhag, Air Force chief Air Chief Marshal Arup Raha, the Intelligence Bureau’s Rajeshwar Sharma, and the Research and Analysis Wing’s Rajendra Khanna.

Since both the cars—Ikagar’s Innova and the SP’s XUV—had driven in the direction of Pathankot, it was surmised that the target was in Pathankot, a militarily high-value town. “It could be that Ikagar resisted when he learnt that the errand was more sinister than drug-running and was killed. In the scuffle, the car could have hit a rock and been damaged, as it has been found so. It could be then that they stopped the SP’s car,” said a senior intelligence officer.

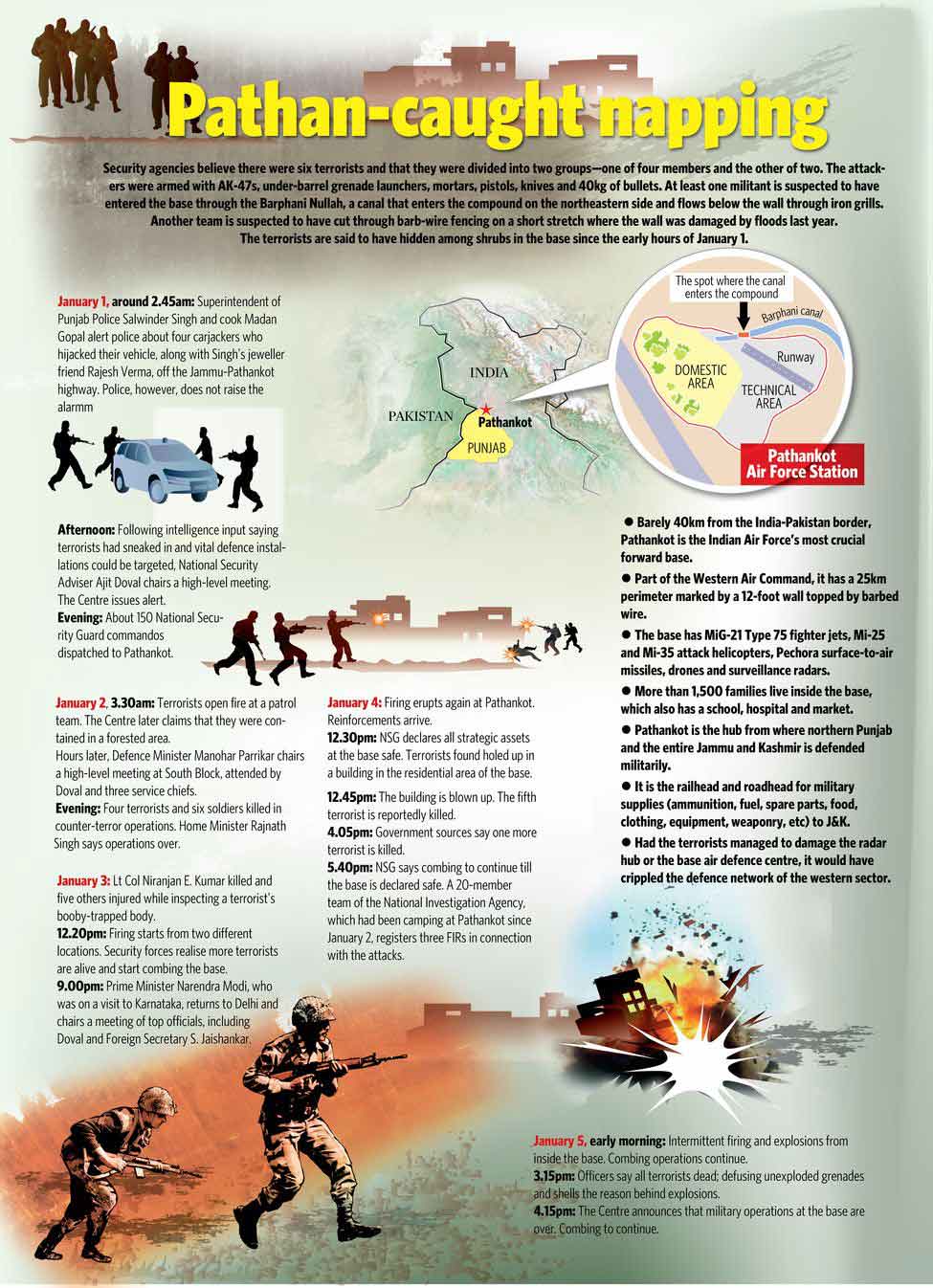

The XUV was soon found a few kilometres outside Pathankot town, which hosted the Air Force station, one of India’s oldest and most sensitive, which based the 26 squadron of MiG-21 Type 75 fighter-jets, the 125 Unit of Mi-25 and the lethal Mi-35 attack helicopters, an unknown number of Israeli Heron spy drones and some of the most sensitive air defence radars that scanned the horizons 24 hours and 365 days a year.

“Those are some of the radars that have never stopped turning,” said an air marshal who had commanded the base. “That stretch of 9,000 metres of asphalt is perhaps the most scorched runway we have in India. You cannot imagine the amount of flying that is being done from there every day. And you got to be very careful. Within three minutes of takeoff in the wrong direction, and you are in the Pakistani skies.” The base also housed around 3,000 personnel and together with their families about 11,000 people.

The aircraft could be quickly removed—a few were actually flown out to Amritsar—but the stationary radars and the Pechora air defence missile batteries remained vulnerable. The radars attached to the missile batteries were the ones that secured the entire stretch of skies over southern Jammu, part of Himachal Pradesh and the entire northern Punjab.

Close by in the cantonment were two divisions of the Indian Army, tasked with the defence of the tricky sector where the Punjab plains slowly roll into the hills. And then there was the railhead, right in the cantonment where goods trains disgorged tonnes of military supplies—fuel, oil, ammunition, small arms, spare parts, food, rations, clothing, everything—every day, from all over India. From Pathankot they are despatched in hundreds of trucks every day, up the NH-1A to Jammu, Srinagar, Sonamarg, and further uphill to the strategically vital Zojila, Kargil and finally Ladakh, and to Kullu, Manali and Rohtang. If something happens to the vital logistic line, the military in Jammu & Kashmir will starve of food, fuel and ammunition.

But the most worrying was another factor that had major strategic and diplomatic implications. For, secretly training on the Mi-35 attack helicopters stationed in the base were 25 young Afghan air force officers who had recently come in—just around the time Prime Minister Narendra Modi gifted four of those dreaded birds to Afghanistan. The worry now was: were the terrorists coming in to hit them? In that case, how did they know? It was only then that the significance of the recent arrest of an airman, K.K. Ranjith, dawned on the strategic community. Ranjith was arrested just a week earlier, after he was found sending details about Air Force stations and bases to a Facebook friend who had honey-trapped him.

“Their [the terrorists’] objective was to destroy IAF assets and create an atmosphere of chaos in the country, where even the military was not safe from their evil designs,” said Air Marshal A.K. Singh, former western air commander.

From the meeting, Doval called the National Security Guard. By the time the meeting was over, the NSG commander in Manesar had asked 300 of his best boys drawn from the 51 and 52 Special Action Group teams, who had trained with the American forces, to fly out. The head of Aviation Research Centre, the aviation wing of the R&AW, was asked to prepare a special Ilyushin aircraft to fly them.

By then, western air commander Air Marshal S.B. Deo had alerted the air office commanding Pathankot, Air Commodore J.S. Dhamoon, who, in turn, alerted the commander of the Army’s 21 division to lend forces if needed. In a couple of hours, Deo himself landed at Pathankot with a posse of Garud commandos he had picked up from Adampur base on the way. By 5pm, the local police had cleared all vegetable vendors, tea-sellers and petty shopkeepers from the vicinity of the station, and shut all entrances to the base. As they moved the barricades about a hundred yards ahead, closer to the civilian township whose many houses share the boundary walls with the Air Force station, the townspeople, who had already heard the news of the SP’s abduction, panicked. Recalled Ashok Mehta, who has a shop next to the station’s main gate: “By 8, the entire market was shut, two hours before the usual time.” So were all the five gates of the station, one permanently shut and the remaining four manned by sentries of the Defence Security Corps, a force of retired soldiers who guard most military stations across the country.

In that stillness, six men sneaked into the fortified and sealed Air Force base. How? Therein lies the biggest mystery of the Pathankot siege, bigger than the mystery about how they sneaked into India. Or had they sneaked in before the alert had been sounded and the base sealed?

Theories abound. The base is protected by a 12-foot-high wall, which runs all around its 25km perimeter. And on top of the wall is a thick fence of concertina and cobra wires. Every 500 metres there is an observation post, which is eight feet higher than the fence, and is manned by more than 300 sentries from the Defence Security Corps. The entire area is well-lit, and there are about 60 sentry posts. “In every such station there would also be a patrolling path which runs inside more or less parallel to the perimeter wall,” said retired air marshal Bharat Kumar. In such stations, where there was an alert, patrol parties would have been going round.

THE WEEK correspondent and photographer drove around outside the perimeter wall along the metalled roads and unpaved tracks, which took them to a populated area called the Garden Colony. Beyond that are a stretch of jungle, a nullah, a bridge, and a few towers, and yonder was Akalgarh, where the SP’s XUV had been found.

One theory is that the infiltrators had made use of a large gap in the wall that had collapsed a few months ago. Another theory is that they could have sneaked in through some of the drain pipes that have been remaining dry for months. The walls did sport sewage and drainage outlets, some eroded in parts and breeding pigs. But what made the wall look vulnerable is the wild growth between the road and the wall—dense enough for anyone to hide. “The Air Force did not have the budget to clear that,” said an officer. But Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar refused to give any clue. “Until the investigation is complete, we cannot tell you from where they would have entered.”

Air Force officers in Delhi said the terrorists lay waiting in the wooded area of the base till around 3am. They had made a couple of calls from jeweller Verma’s phone to certain Pakistani numbers, but had switched off the phone by late afternoon.

By then, the Air Force’s Heron spy drones, equipped with night-spotting cameras, had spotted the terrorists lying in wait some 400 metres from the technical areas. A Garud crack team of Squadron Leader B.K. Dubey, Commando Manoj and Commando Gursevak quietly moved out. The terrorists opened fire and the team had to retreat.

And then it happened. Gursevak’s Tavor assault rifle jammed after firing 20 rounds, and as he stood perplexed, a spray of bullets hit him. Dubey and Manoj were also hit, but they continued firing at the terrorists, who ran towards the DSC cookhouse, where food was being prepared for the whole station, including more than 1,500 sudden ‘guests’ in the form of NSG, Army and additional Garud commandos. On the way, the terrorists spotted Subedar Major Fateh Singh, who was going for his shift of duty, and fired at him. The ace shooter, a Commonwealth Games medallist, was the second casualty. Three others, taking bath for their shift of duty, ducked to save themselves.

The action stirred up the whole base. The terrorists moved into the cookhouse, where morning tea for the sentries was being made, and spewed bullets killing four DSC jawans, and walked out.

It was then that the base ‘witnessed’ the most gallant action in the entire episode. Seeing a few terrorists walking away after killing his comrades, DSC sentry Jagdish Chand pounced on one of them. The professional wrestler that Chand was, he overpowered the terrorist, snatched his AK-47 and shot him, the bullets flying out the enemy’s head. But, in no time, the other terrorists cut Chand down to a true hero’s death.

The terrorists now split into two groups of four and two—one moving into a building which stored furniture, and the other lying low in a pit surrounded by tall elephant grass. It was clear that they had received military training. They were careful that one group engaged the security forces, while the other rested. The security forces felled four of them in that exchange of fire, but did not know whether they were dead or lying in wait.

Outside the base, Ashok Mehta and other townspeople “felt like we were being attacked. We had felt safe because of the Air Force base. Now the base itself was under attack.” The nightlong combing did not yield any body, dead or alive. On the morning of January 3, a grave error triggered a tragedy. While trying to defuse a bomb on the fourth terrorist’s body, the NSG’s bomb expert Lt Col Niranjan Kumar was blown to death.

As word spread of that loss, more troops were brought in. Three-tonner trucks, bulldozers and JCBs drove in and out with soldiers in battle fatigues. “A total of nine columns from Jammu & Kashmir Rifles, Sikh Light Infantry and Sikh Regiment were sent by the Army,” said an officer in the Army’s operations directorate in Delhi. General Dalbir Singh Suhag ordered that Casspir mine-protected vehicles be sent in for the operation. “When we found that there were only two vehicles available at Pathankot, we asked the Army’s Northern Command in Udhampur to lend seven more. We also asked the Pathankot commander to use BMP armoured personnel carriers,” said an officer in the Army’s operations directorate. “All this helped us to minimise casualties on our side.”

The resolve to hit back and kill was there, but patience was the mantra. More than 72 hours into the operation, Major-General Dushyant Singh of the NSG would not be hurried. “The operations to secure the airbase is smooth, given its magnitude,” he said in his first media appearance. “It will continue till everything is cleared. It can take a long time.” Brigadier A. Bevli agreed. Air Commodore J.S. Dhamoon would explain later that the worry was always about the nearly 11,000 people who were staying in the base.

Finally, the NSG rolled a surveillance ball inside a room in the furniture store building and found two terrorists hiding in a concrete almirah. Again there was a worry. There were 11 Army and Air Force personnel stuck on the third floor. They were quietly evacuated. And then started a ‘quiet storming’ of the building, which brought it down by the evening of January 3. It marked the end of a prolonged siege.

Was it too prolonged? “No,” Ajit Doval told THE WEEK. “Had we shown haste, we could have lost more men. But since they [terrorists] had been cornered, the forces on ground decided that we will go slow and avoid casualties of own men.”

Moreover, as it was pointed out, the actual operations were completed in almost 30 hours, but the forces declared an end to the operations only after a thorough combing for explosives that could have been planted.

Still, questions remained. One, who were the six attackers? According to sources in the intelligence hierarchy, the six were members of Al Rehman Trust in Bahawalpur, which is actually a front organisation of the extremist group Jaish-e-Mohammed, and had been trained at the Chaklala and Lyallpur airbases of the Pakistan Air Force. The leader was called Nasir. Most of the training was coordinated by an Ashfaq Ahmed and a Haaji Abdul Shakoor in Bahawalpur.

The six seemed well-versed with the manner in which Air Force bases are laid out between technical areas and living areas. During the operation, a handler called Kamaal Jaan from Sialkot guided them over the phone. Occasional contact was also made with a person located near the Shakargarh bulge in Pathankot in Pakistani territory.

And, why did they come? “A particular aluminium explosive powder has been recovered from the bodies which, if thrown over the parked aircraft could have been highly incendiary,” said an Air Force officer. “The fellows could have set fire to several aircraft like that.”

Did they come for the Afghan pilots and technicians? “Probably,” said an officer at the base. “Anyway, it would have been a major embarrassment had they been held hostage even for a few hours.” In fact, it was what worried Air Marshal Deo the most. Deo told Dushyant of his fear and the two even worked out a plan to evacuate the Afghan technicians and pilots.

The unanswered question: How did the terrorists enter the base? Even Parrikar would not hazard a guess. “Investigations will find that out,” he said.

with R. Prasannan in Delhi and Vijaya Pushkarna in Pathankot