At 3am, Nishchay Luthra’s phone sounds the alarm. The figure skater jumps out of his bed, puts on his trainers and goes for a jog. He then cycles for about three kilometres to reach his academy, goes inside the rink and practises double axels, broken-leg spins and triple-toe loops, till they are almost perfect. Then he returns home and crashes into the bed.

The Adidas campaign video that urges viewers to support the athlete ends here, but the 18-year-old’s dream does not. “I want to win the Olympic medal for my country,” he tells THE WEEK over the phone from Florida, where he is now based. “If not immediately, the next time; but I will win.”

Staying away from his family and homeland has been tough for him. “You have no one to fall back on,” he says. “I have to prepare food, keep myself motivated and fit, and tend to injuries—all on my own.”

Nishchay is recuperating from a twisted ankle he got while practising “using old skates”. He wants to represent India in the Winter Olympics in South Korea next year. The Adidas campaign has helped him gather support from the likes of cricketers Rohit Sharma, Rishabh Pant and K.L. Rahul, and actor Ranveer Singh.

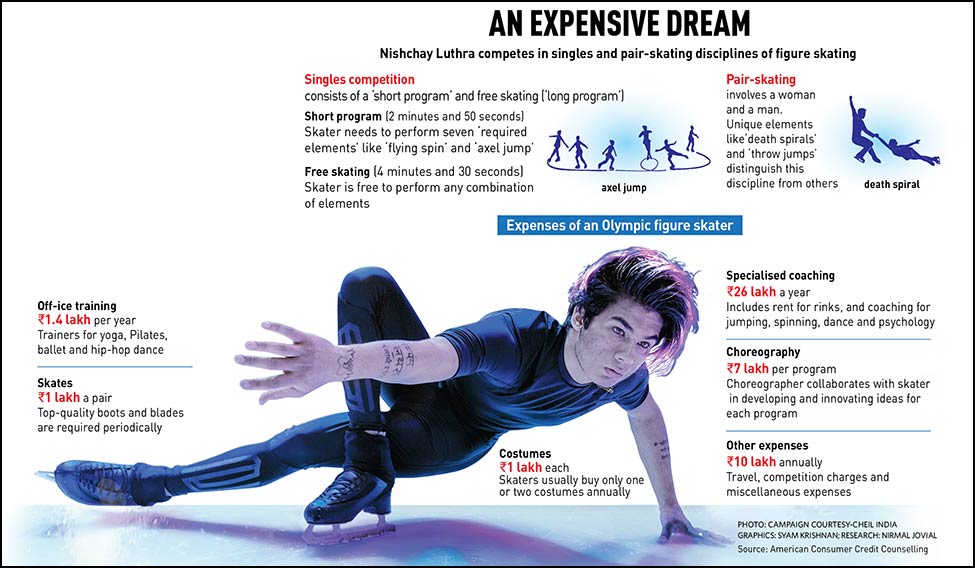

What he now needs is financial support. “Because of lack of funds, I am losing out on training time,” says Nishchay, a class 11 student at The Indian School in Delhi. “I need to train at least four hours a day, but I can only train for half an hour, four times a week. While other kids are taking up to 21 lessons, I am taking four half-hour lessons in the same amount of time. I try and watch online videos, but that is not enough to win a competition of this level.”

To use the Panthers Ice Den, an advanced skating rink in Florida, Nishchay has to shell out $100 (approximately Rs 6,400) an hour. There is also the fee of Adrian Schultheiss, his Swedish coach and 2010 Winter Olympian.

This year, Nishchay will participate in the Junior Grand Prix of Figure Skating in Australia and Poland. Expenses for both tournaments will be borne by the Ice Skating Association of India.

ISAI director Col S.C. Narang, however, says chances of Nishchay qualifying for the Winter Olympics are slim. “Considering the lack of good infrastructure and coaches here, Nishchay took the right step by moving to the US for training. However, I doubt if he will qualify for the Winter Games this time, as every time we have asked him to participate in an international or national competition, he has not shown any interest. Participating in such competitions helps you know your level of preparation and hone your skill. But, if he continues to work hard, he may qualify for the Winter Olymipcs next time.”

Nishchay took to ice skating he was just 10. “Since his childhood, Nishchay was exceptional in sports,” recalls Neelam Luthra, Nishchay’s mother, a former athlete. Figure skater Vasudev Tandi, who had coached Nischay in roller skating in school, prodded her to enrol him for figure skating. “He said Nishchay was champion material,” says Neelam. “And I thought: what I couldn’t do [win a medal for the country], my son would.”

They took him to participate in an ice skating competition in Shimla. “All we wanted was to know whether he would be able to do ice skating or not, but he returned with a gold medal.”

That was just the beginning. Between 2011 and 2016, Nishchay won nine gold and three silver medals at national events and a bronze at the World Development Trophy in Manila in 2014. Lack of infrastructure and international-level coaches impelled him to move to the US in June 2015. But he returned to India after six months because of lack of funds.

Nishchay received Rs 9 lakh in two instalments from the National Sports Development Fund, says Neelam, who is head constable at the central police control room of the Delhi Police. “But the amount we received in one tranche (Rs 4.5 lakh) was just enough to take care of training expenses for a month. So, we mortgaged our house and took loans from friends to meet the cost,” she says. The government is yet to release the remaining Rs 1 lakh.

It is about 5 in the evening and the rain gods are kind. The narrow spiral staircase that takes me to the third floor of Nishchay’s ancestral house at Kalkaji in South Delhi is slippery. Prachi, his 17-year-old sister, welcomes me. It is a spacious house, but not very well-maintained, probably because of the money crunch. The sofa covers are torn, but the dim light of the crystal chandelier almost hides it. On the left is a wooden cabinet filled with medals and trophies won by Nishchay.

As I am looking at the cabinet, a pug named Cherry starts circling me. “Nishchay loves him,” says Prachi. “Every time we video chat, the first thing he will enquire is, ‘How is Cherry?’”

She feels a bit embarrassed about discussing her family’s financial struggles, but says Nishchay’s achievements more than make up for it. “Everyone in school now knows me as Nishchay’s sister and wants to talk to me. I feel so proud!” says Prachi.

Neelam asks her to go and study for her upcoming exams. Prachi is “childish”, she says, while the family’s struggles have made Nishchay very mature. “When I start breaking down, he consoles me and gives me strength,” says Neelam. “I remember taking him for boot camps outside Delhi. We used to stay in dharamsalas and gurudwaras to save money. I didn’t even have money to buy him an energy drink during breaks.”

They have come a long way from that, but the struggles remain. “What I miss the most is the healing touch of my mom,” says Nishchay over the phone. “But all this hard work is worth the dream I am chasing.”