Two months after news of the first spate of deaths of newborns in Gorakhpur made headlines, the Union ministry of health and family welfare found a reason for some cheer. The cause for "celebration" was the recent data that showed less children were dying in the country.

According to the latest Sample Registration System Bulletin, India had registered a significant decline in its infant mortality rate, or deaths under 12 months. The IMR had fallen from 37 per 1,000 live births, in 2015, to 34 per 1,000 in 2016.

Even as the government patted itself on the back for the "success", the irony in the numbers became rather evident—90,000 kids had been saved in a year, but 8,40,000 infants were still dead before their first birthday.

"Our institutions have completely failed our children," says Dr Yogesh Jain, paediatrician and public health physician with the Jan Swasthya Sahyog in Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh. According to Jain, a crisis such as the recent deaths of infants in Gorakhpur, Jharkhand, Farrukhabad, Nashik and Bokaro, can be attributed to a lack of investment in public health institutions, particularly in district hospitals.

"The focus has been on improving community processes such as training health workers, better nutrition, or even immunisation programmes. While those community processes are important, there has to be investment in hospitals, which is really the need of the hour," says Jain.

Jain, who left Delhi with eight other doctors from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences to set up the JSS in Chhattisgarh in 1997, points to the state of the special newborn care units at the hospitals where the recent deaths occurred, and the weak systems there. "Some of these district hospitals have a death rate of 25 per cent in their paediatric wards. This is just unacceptable," he says.

A cry for help: A one-month-old in Karnataka who weighs less than 2kg | Jagadeesh N.V.

A cry for help: A one-month-old in Karnataka who weighs less than 2kg | Jagadeesh N.V.

In an editorial published in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics in September, Jain, along with Keshav Desiraju, former secretary, ministry of health and family welfare, highlights an instance of weak systems in hospitals: "A haunting fact that shamed us all is that when the oxygen supplies were failing... the nurses and doctors of the paediatric and neonatal intensive care units handed self-inflating bags called ambu bags to several parents of these very sick children and asked them to pump air into the lungs through their mouths and noses. Bagging air using an ambu bag is a skilled job and can scarcely be handed over to a novice."

The weak system also reflects in the lack of a clear diagnosis, he says. In the case of the Gorakhpur deaths, the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), believed to be the main cause of the deaths each year, was found to be the reason only in 10 to 15 per cent of the deaths this time. As it turned out, one of the main reasons behind the deaths—the consensus seems to be that it was a mixed bag of infections—was the re-emerging bacterial disease of scrub typhus, a fact that was confirmed by Dr Soumya Swaminathan, director general, Indian Council of Medical Research, and secretary, department of health research.

If Jain stresses on curative methods— increasing investment in secondary-care institutions such as district hospitals and community health centres, instead of the resource-intensive tertiary-care ones such as AIIMS—others are batting for the preventive approach to avoid disease and death. Dr H.P.S. Sachdev, paediatrician and senior consultant, Sitaram Bhartia Institute of Science and Research, Delhi, feels that a developmental approach is necessary to find solutions to the infant crisis. "The roots of infection lie in poverty, bad nutrition, poor sanitation and early marriages," he says.

While immunisation has helped eradicate several diseases such as small pox and polio, there are newer challenges such as the avian flu, dengue, and multi-drug resistant tuberculosis that are emerging, says Sachdev. "Of course, quality of care at hospitals is extremely important, and we do need trained manpower such as doctors, nurses and auxiliary staff, too. But, the issues around disease and death cannot be resolved unless we address aspects such as nutrition and hygiene," says Sachdev.

If one looked at India's nutrition problems alone, the extent of the crisis is vast. Consider the latest data from the Global Hunger Index: more than one-fifth (21 per cent) of children under five weigh too little for their height (wasting), and over one-third are too short for their age (stunting).

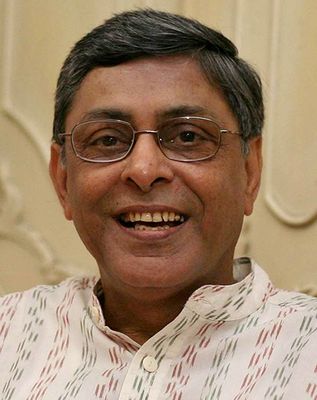

Dr Arun Gupta

Dr Arun Gupta

Only three other countries in this year’s GHI—Djibouti, Sri Lanka, and South Sudan—show child wasting above 20 per cent. Experts say while the rate of stunting has improved—down 29 per cent since 2000—the wasting rate has not displayed any substantial improvement in the past 25 years.

According to the National Institute of Nutrition in Hyderabad, the prevalence of stunting among urban children under five was highest in the states of Uttar Pradesh (40.8 per cent), Maharashtra (36.4 per cent), Delhi (35.7 per cent) and West Bengal (34.4 per cent).

Families in India still lack the knowledge of and the access to nutritious food, says Dr Arun Gupta, member, prime minister's council on India's nutrition challenges. Gupta, who also heads the NGO Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India, says that it all starts from the first hour of birth—only about 44 per cent of newborns get mother's milk within an hour of birth.

"The rest get formula milk. Many times, the safety of the formula feed—some kids are even given animal milk and water—is not ensured. Families are not educated about how to, for instance, sterilise bottles for feeding. This leaves the babies susceptible to infection," says Gupta.

Other problems, too, hamper infants' access to complementary feeding after they complete the six months of being exclusively breastfed. "At this point, they need to be given at least four different food groups to provide them both calories and micronutrients. But according to NFHS 4 (National Family Health Survey), only ten per cent of the infants eat four food groups. Denied this vital nutrition, kids slip into nutritional deficiencies," says Gupta.

Corruption in government schemes to enhance nutritional status, such as Integrated Child Development Scheme, also results in children being malnourished. A recent study done by The School of International Development, University of East Anglia, UK, found that corruption and high staff absence from duty had rendered the scheme "near dysfunctional".

Dr Yogesh Jain

Dr Yogesh Jain

In its zeal to find solutions to such nutritional challenges, particularly for children suffering from severe acute malnutrition or moderate acute malnutrition, plans are also afoot to introduce ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) in some states, a step which has generated considerable debate among experts. RUTF is an energy-dense paste, made out of peanuts, oil, sugar, milk powder, and powdered vitamins and minerals.

Both Gupta and Sachdev argue against the use of packaged food such as these to treat malnutrition, in favour of sustainable solutions such as locally sourced food products. Gupta says that studies have proven that there is "inadequate data to recommend therapeutic food—for home-based treatment of severe acute malnutrition in children from six months to five years—over a flour porridge-based treatment regime". While the model has proven to be "successful" in Rajasthan—children have gained weight after eating it—Gupta says that the Nutrition Advocacy in Public Interest, a national think-tank, wrote to J.P. Nadda, Union minister for health and family welfare, questioning the efficacy of RUTF. Their concerns were shared by the minister and the ministry distanced itself from the programme.

"Children need real food, not packaged products that are expensive and not sustainable as solutions," says Sachdev. "We must not get carried away by solutions from the developed world. And then, geographical variations also matter—what might work in remote tribal areas will not be good for urban areas." For a developing country in transition, policymakers have the unenviable challenge of dealing with the twin burden of under-nutrition and over-nutrition, which is causing a rise in obesity among young children, adds Sachdev.

Whether it is the confounding problems of nutrition or the poor infrastructure in the hospitals leading to deaths of newborns, it is time that policymakers took up the cause of the young ones.