Raunak Trivedi, 13, loves cooking. He would gladly treat you to an experimental pasta dish, perhaps little realising how unusual it would have been for a boy his age to have such a hobby 25 years ago. His passion is clearly a child of the internet—the source of many of his culinary creations—and the influence of television shows like MasterChef and Hell's Kitchen.

His grandfather, 85-year-old Ramesh Trivedi, is barely in a position to appreciate Raunak's talent, being a vegetarian. A physician, Trivedi loathes mobile phones and the internet, and sees them as distractions rather than necessities. In fact, a board outside his dispensary in Prabhadevi, Mumbai, states that he does not offer medical advice over the phone. “You will exaggerate or understate the symptoms or you will misspell the medication I name. The network is so bad half the time. I have no truck with that kind of thing,” he says.

Dr Trivedi's son and daughter-in-law have dealt with the advances in technology in their own ways. They are the bridge between Raunak and Dr Trivedi and, as such, they embody the halfway house between them. Sunanda, 50, the daughter-in-law, remembers using a mobile phone for the first time when Mumbai was flooded in 2005. She bought her own handset two years later. Her husband, Tushar, an advertising executive, came to terms with technology more gradually. Like many of his generation, he had not anticipated in 1995 that what was being called the personal computer would go on to become more personal than just a computer. “I was too lazy. I didn't know the office applications very well. I just managed. I knew e-mail, how to start the computer, how to shut it. I could have learnt more in 1995, but I didn't. I felt that somebody around me can always take care of the rest,” he says. After years of worrying that his debit card details would be hacked, he first used it at an ATM in 2007.

Dr Trivedi's wife, Indu, also a physician, represents yet another nuance. She has a cellphone with a keypad—the dumb one, as some would call it. She uses it to make calls. For most other functions, she seeks her grandson's help, which, she admits, also comes in handy while operating the television. While she wishes she was more savvy in these matters, she is charitable enough to say that the cellphone has “revolutionised” people's lives.

Shoppers' stop: Malls mushroomed in Indian cities after 1991.

Shoppers' stop: Malls mushroomed in Indian cities after 1991.

It has been a revolution—one so complete that it is easy for the Trivedis and the rest of us to forget that it all began with a near disaster in India's economic history.

ON JUNE 20, 1991, cabinet secretary Naresh Chandra walked up to P.V. Narasimha Rao, who was to take over as prime minister the next day, with “a top-secret eight-page note highlighting the urgent tasks awaiting the new prime minister,” writes Jairam Ramesh in To the Brink and Back: India's 1991 Story. “When he saw the note, Narasimha Rao's first response was: 'Is the economic situation that bad?' To this, Naresh Chandra's reply was, 'No, sir, it is actually much worse.'”

Chandra was not exaggerating. As he and Rao spoke, India's foreign exchange reserves could afford only two more weeks of imports. They had dropped from $3.11 billion at the end of August 1990 to $896 million by mid-January, as the Gulf War progressed and the prices of crude oil spiralled. A legacy of short-term borrowings made in the 1980s weighed heavy on the country's credit profile. Yashwant Sinha, the finance minister in the Chandra Shekhar government, had already mortgaged 20 tonnes of gold to Bank of England in exchange for $200 million and presented an interim budget two days before the minority government fell on March 6, leaving India in the middle of a balance-of-payments crisis.

That Rao had grasped the magnitude of the problem was evident from the fact that the next day he persuaded former Reserve Bank governor Manmohan Singh, a widely respected academic, to take up the finance portfolio. It was clear to everyone in the government that the situation demanded drastic measures, which could even signal a departure from the socialist moorings that had held firm sway over the economy since independence.

To that extent, both Rao and Singh had been set tasks against their grain. The prime minister had a reputation for indecisiveness and was hardly one who would be expected to enforce a directional change in the history of a nation. Singh was seen as a chip off the block of stolid Nehruvian socialism and sceptical of a market-driven economy. (A year later, in the wake of the Harshad Mehta scam, he reaffirmed this stand. “I don't lose sleep over what happens in the share market,” he said.) The next two months saw the unravelling of these reputations.

The first indication came on June 25 when Singh addressed his first news conference as finance minister. He said he had no 'magic wand to bring down prices'. This was seen as a departure from a promise in the Congress party's 1991 election manifesto to “roll back prices to levels obtaining in July 1990” of ten essential commodities within 100 days of coming to power.

The next step was to devalue the rupee in order to affirm the country's commitment to moving to a free-market economy. This was a necessary preliminary to obtaining support from the International Monetary Fund. At the same time, it was an emotive issue for a country like India, which had long been used to a managed currency. For the Congress, it was particularly difficult, as the party had not forgotten the fallout of a similar exercise in 1966 when the Indira Gandhi government devalued the rupee only to find the west reneging on its end of the bargain. Yet, in the absence of a viable alternative, the government pushed ahead with devaluation.

Ajit Balakrishnan | Amey Mansabdar

Ajit Balakrishnan | Amey Mansabdar

The rupee was depreciated by 18 per cent against the major global currencies between July 1 and July 3. More gold was flown to Bank of England over the next 15 days. On July 4, commerce minister P. Chidambaram announced a revamped trade policy, abolishing mechanisms of arbitrary control, such as licensing, linking all non-essential imports to exports and stating explicitly that the rupee would be made fully convertible on the trade account in three to five years.

The government executed these moves amid widespread criticism of the trajectory being followed by it. There was a clamour for alternatives from outside the government. West Bengal chief minister Jyoti Basu wrote to the Centre asking to tap the wealth lying with non-resident Indians to salvage the situation. In July, 35 left-leaning economists issued a statement suggesting, as solutions to the crisis, a more restrictive import regime, better fiscal management through improved tax collection and controlled expenditure, and export incentives.

Some within the higher bureaucracy shared the views. Ramesh writes that finance secretary S.P. Shukla, chief economic adviser Deepak Nayyar and foreign secretary Muchkund Dubey were not enthused by the prospect of liberalisation. “It was an extraordinary situation—the entire reforms programme was conceived and executed without the full and active participation of the finance secretary and the chief economic adviser.” The prevailing view was that India was being made to sell out to the IMF.

When Singh finally presented the budget on July 24, putting an end to decades of what was called the 'licence-permit raj' and opening up India's industrial sector to unfettered private participation, he was speaking to a largely hostile audience of parliamentarians. Rao and he took on questions from opposition members from across the political spectrum with conviction to eventually make the proposal sail through.

Ramesh recounts one interesting point during the debate when Parliament witnessed the peculiar scene of a reformist prime minister speaking for the rights of the most underprivileged of Indians to rebut the allegations of a communist. Nirmal Kanti Chatterjee, a Marxist MP from West Bengal, said mechanisation resulting from the reforms would throw a number of people out of their jobs. Rao took the example of washing machines to argue that while they could cause some people to lose their jobs, they had the potential to make up for that on the manufacturing side. Besides, there was the question of quality of the job. “If you take that as the criterion then you will remain a country of maid-servants only...,” Rao said. “You are condemning our women folk to a life of drudgery permanently. This is where diversification is necessary. That is why we have not given them any education so far. Let her be educated. She will refuse to do the washing, the moment you educate her... It is very simple to say that 'you are throwing people out of employment'. But what kind of employment?”

AN ANSWER TO Rao's question can be found in Raigad in Maharashtra. Karuna Prakash Mukadam, 36, came to live in Wawanje village of Taloja when she got married 18 years ago. Till four years ago, she had imagined herself only as a homemaker, with her role in a local self-help group being the sole exception. That changed in 2011 when the financial technology company FINO PayTech approached her with a proposal to be their business correspondent and help acquire clients for their deposit-taking service.

Mukadam was apprehensive. She could not fathom how she would work with technology of any sort without knowing English. Then, Rs1,500 seemed too small an amount for the effort it would take to go from door to door seeking deposits. Most importantly, she doubted if people would trust her.

Bitter harvest: India has been slow in aiding agricultural growth | AP

Bitter harvest: India has been slow in aiding agricultural growth | AP

She eventually took up the offer on the consideration that whatever she earned would compensate the expenses she anyway incurred while travelling to 24 villages under the coverage of her self-help group. Her other fears, too, were dispelled soon. Officials from the closest branch of Oriental Bank of Commerce accompanied her in the initial days as she went looking for clients. A three-day training in using a card swiping machine prepared her for her new role. She now understands it well enough to tell you, “This machine is as good as a small bank.”

Mukadam's colleague Ujjwala Krishna Sangle, 38, walks for two hours every evening to take the service to the tribal village of Khana cha Bangla, whose residents do not have access to electricity but can now maintain savings accounts. Most of their clients are homemakers; many of them use the service to keep their savings out of the reach of alcoholic husbands. There are instances of women using these savings to start a fishing or tailoring venture.

The association with FINO has not only given women like Mukadam and Sangle an additional source of income, but also earned them the respect and confidence of their clients and fellow villagers, who at times consult them on how to manage their money. A life of such dignity for women at the grassroots might not have been possible had the reforms of 1991 not created conducive conditions for firms like FINO.

While Mukadam's is one of the lesser-known success stories of the reforms, some others are part of history. Zee Telefilms became India's first private broadcaster in 1992 and soon began to challenge the hegemony of Doordarshan with offerings such as Tara, Banegi Apni Baat and Antakshari. The format of Antakshari, a game which required each participant to sing a song beginning with the last letter of the song sung by the participant immediately before them, became a rage across India over the years, with people playing it at family gatherings and social functions or when they were simply bored. Writes Shoma Munshi in Remote Control: Indian Television in the New Millennium: “Antakshari introduced format programming to the Indian viewer, even before international formats were brought into the country.” This was a triumph of the channel's decision to cultivate talent in-house and position itself somewhat differently from the state-owned broadcaster. The average programming cost was around Rs30,000 an hour for the first year, says Subhash Chandra, founder and the chairman of the company, now called Zee Entertainment Enterprises.

Chandra had had quite an experience launching the company. He was toying with the idea of launching a travelling video van service or a cellphone company in 1990 when a “casual visit” to Doordarshan's Mumbai office gave him the idea of foraying into broadcast instead. But this was pre-reforms India, and Chandra soon got a taste of it. “When I decided to launch a private satellite channel, I met with road blocks at every stage,” he says. “In fact, when I broached the subject with the then secretary for information and broadcasting, he was livid and he thundered, 'You will introduce consumerism and destroy the country. Your proposal can fructify only over my dead body'. I then approached several legal luminaries, but all of them shot down my proposal. “However, I was not ready to take 'no' for an answer, and so I worked out a strategy. The question I asked was simple: if foreign channels like CNN and BBC could be viewed in the country, why not a private Indian channel?”

He eventually succeeded in setting up the channel by changing the name of his company, Empire Holdings, to Zee Telefilms Ltd, which provided content to Zee TV Hong Kong, which, in turn, beamed the signals into India from Hong Kong. These manoeuvres might have been unnecessary if Chandra had waited a little longer. He admits that there was a positive change in the attitude of the government after 1991. “The ease of doing business vastly improved and there were some important policy changes as well which benefited the blossoming television industry,” he says.

This ease of doing business was expected to substantially benefit the setting up of physical infrastructure. However, India did not have any institutions dedicated to funding the creation of infrastructure. In 1997, this gap was addressed by the formation of Infrastructure Development Finance Corporation, now known as IDFC, on the recommendations of the expert group on commercialisation of infrastructure projects, headed by Rakesh Mohan. A task force comprising representatives from the Central government and a number of financial institutions was formed and this group came up with a report detailing a business plan. The initial years were challenging as the company had no homegrown models to go by. “We wanted to offer products which were not being offered by other financial institutions. Secondly, the whole concept of infrastructure was new because there was no security, unless you were setting up something like a power plant, where real capital assets were being created. Cash flow as security was a new concept,” says D.J. Balaji Rao, the first managing director of IDFC. “For the first three-four years, we did not envisage sanctioned disbursal as the principal criteria because there was no point in our sanctioning assistance and stipulating conditions. Clients would not be able to comply with them.”

So IDFC started by investing in a few existing companies and state government projects. Simultaneously, it was speaking to governments and the Planning Commission to resolve issues that had been holding up the process of infrastructure creation. Back in the 90s, the company recommended privatisation of state electricity boards, making power prices market-linked and separation of power production from distribution and transmission. While these tasks remain unfinished, IDFC has endured as a rare successful instance of a public-private partnership. It is today a listed company and has diversified into merchant banking, private equity, asset management and banking.

Balaji Rao says that while some structural impediments to infrastructure creation persist, 1991 took care of much that was unpalatable. “Today, if somebody is losing money, it is because of their own inefficiency and incapability,” he says.

Another company that seized an opportunity was Fortis Healthcare. The hospital chain, which started building its first hospital in Mohali in 1999, had no existing business model to emulate, and dealt with teething pains in the early days. The Mohali hospital was initially set up as a facility dedicated to cardiac health. The company had decided to follow a hub-and-spoke model. “We later realised that the fully cardiac facility and the hub-and-spoke model were not feasible. So we made it into a super-speciality hospital with different specialities at the tertiary level and that worked. We then picked up a plot in Noida and built the second hospital there,” says Malvinder Mohan Singh, executive chairman of Fortis.

However, the kind of medical talent Fortis required to meet its stated objective of providing world-class health care was not forthcoming. “Over the years, talent has clearly been one of the biggest issues because there is a shortage and there is no structured talent pool for health care management,” says Singh. “So we spent a lot of time and effort in training, developing and nurturing our own talent pool in-house because there was nothing available in the market. We continue to do this.”

There were others who spotted opportunity in sectors that were freed of state-owned monopoly. Armed with his 36-year-long experience in international airlines in varied functions, Naresh Goyal floated Jet Airways, India's first private carrier, in 1992. Jet now flies to 73 destinations, 51 of them in India, and, along with partner Etihad Airways (which owns 24 per cent stake in Jet), operates 4,300 flights a month.

The greatest success story of the reforms, however, was the telecom revolution, which resulted in the cellphone reaching practically every village of the country. Among the earliest to foresee this scenario and the one to reap the greatest dividends from it was Sunil Bharti Mittal. In 1991, his company, Beetel, was making push-button telephones and while vacationing in Goa he saw a newspaper advertisement announcing the opening up of mobile telephony. In the auction that followed, he won the licence for the Delhi circle, and Bharti Airtel was launched in 1994. It is now India's largest telecom service provider with 243 million subscribers.

Airtel is often cited as a shining example of how nimbler new ventures can stave off bigger rivals. “Look at Sunil Mittal,” says a leading angel investor. “He was a startup. But he took on Reliance.” Airtel, indeed, was a startup, the first of many to come.

Tough job: Labour unions have been steadily losing their relevance since 1991 | AFP

Tough job: Labour unions have been steadily losing their relevance since 1991 | AFP

ONCE INDIA BECAME a free-market economy, whatever happened in the west, especially in the US, began to drift across to Indian shores. The startup revolution (which would go on to be the dotcom burst of 2000-01) was no different. When Google and Amazon were starting to push the boundaries of commerce and human imagination, some risk-takers at IIT Bombay decided to join the party. One of them was Kashyap Deorah, who started his first company, RightHalf, in 2000. When RightHalf was acquired by a US company, he moved to that country and spent seven years there working in tech startups. In 2007, he returned to India and started another company, in the belief that his learning was over.

What struck him the most on his return was one particular fallout of liberalisation. “The most surprising phenomenon was how everyone had a mobile phone, regardless of socioeconomic status,” he says. “When I took a closer look at this phenomenon, I realised that the mobile had become a means to access income opportunity. It was levelling the economic playing field in rural and urban India alike. This formed the core intuition behind my second company, Chaupaati Bazaar.” A phone-based service to connect buyers and sellers, Chaupaati Bazaar was acquired by the Future Group in 2012.

Deorah continues his career as a serial entrepreneur in a country he thinks has still much to do to become a good place for business. “In the nineties, on the back of the success of Infosys, Wipro and IT services, many, including me, imagined that one day the internet and mobile will level the playing field in the domestic consumption economy. Business would be fair, clean and transparent. The new economy will eradicate the evils of licence raj, crony capitalism, corruption and an overall lack of integrity that plagues Indian business dealings. Unfortunately, even as the new economy has arrived, business in India seems to be a new version of the old habits. The lack of integrity in the new businesses makes my heart sink. I am hopeful that good habits will be rewarded eventually and meritocracy will prevail,” he says.

The old order had curtailed the growth of meritocracy in other spheres as well, as the experience of Dilipp Kumar Jain of Mumbai tells you. In his final year of studying homoeopathy, Jain realised that he wanted to be a radio jockey. Back in 2000-01, the only option he had was to join All India Radio, which he did. A few years later, with the opening up of the sector to private players, Jain moved to 93.5 Red FM as an outdoor broadcaster and was soon allotted his own weekend show, Meri Shaadi Kara Do. Was this shift from the extreme sobriety of AIR to the playful tones of a private broadcaster difficult? In fact, it was the other way around. “I had to adapt to the AIR tonality. The real me was what I was doing at Red FM. There were too many mandates at AIR. You had to avoid playing songs that made mention of smoking or drinking. You had to say 'Jai Hind' and 'Vande Mataram' at the end of the day. I felt a lot less inhibited now,” says Dilipp, who is currently with 92.7 Big FM.

The most fascinating journey effected by liberalisation must be that of Manish Mundra. He grew up selling soft drinks in Deoghar, Jharkhand, and was always an entrepreneur at heart. In 1991, something happened to the twelfth-grader, too. “Manmohan Singh was then hailed as a man of commerce and economics. What he did then made me realise the importance of studies, which until then was a second priority for me. I decided to get a degree and start working.”

Years later, while working for Indian corporations, he became a frequent flier. This developed a peculiar passion in him—watching world cinema on flights. By now, Mundra, head of a petrochemical company headquartered in Nigeria, had come to believe in the importance of building a legacy, something that would keep him alive after he was no more. He decided that producing intelligent cinema would be the means to do this. By 2011, he had saved enough to produce a film, and director Rajat Kapoor was hunting for a producer for his film, Aankhon Dekhi. The two serendipitously came together on Twitter, and Aankhon Dekhi went on to become one of the most acclaimed movies of 2013.

Since then, Mundra has supported more independent cinema—Masaan, Umrika and the yet-to-be-released Waiting. Mundra knows that his journey is almost synonymous with liberalisation. “I have a family in Dubai, I am working in Nigeria and the money that I earn is getting repatriated into India and other parts of the world for making films. One of these [Waiting] is getting made by London-based Anu Menon and is shot in Kochi. This is liberalisation,” he says.

LIBERALISATION ALSO MEANT a lot of other things, especially for India's middle class. “Reform actually translates to the middle class asking, 'Has anything changed for me? Have things got better for me?'” says Ajit Balakrishnan, who founded Rediff, one of India's earliest internet companies.

By that yardstick, 1991 was transformative. Not only did the proliferation of white-collar jobs help pull in a large number of low-income families under the broad umbrella term 'middle class'; it also altered the attitudes of the existing middle class. Not always, however, to happy effect. “The emergence of a middle class that allies itself with the elite, which has added a layer of economic inequality to the already existing social divides, is a key change,” says Amita Bhide, professor and chairperson of the School of Habitat Studies and Centre for Urban Policy and Governance at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. “This middle class is highly aspirational, young, and highly aware. The share of the top rich has also increased in relation to the rest of society. Inequality also has a regional dimension, thus infrastructural gaps between rural and urban areas have increased in the post-reform era. Overall, society has become more unequal. Gini coefficients have reached 62 by 2015, putting India along the lines of Brazil.” The Gini coefficient is a ratio used as a measure of inequality in income distribution. A Gini ratio of 0 represents perfect equality and 100 perfect inequality.

Many experts say the reforms gave the short shrift to India's unskilled masses. “The objectives of equity and poverty reduction should have been addressed. Instead hope was pinned on the trickle-down process which has not worked in any part of the world,” says Jayshree Sengupta, senior fellow at Observer Research Foundation's economy and development programme. “Millions were left behind also because of lack of skills, education and assets. They joined the huge informal sector which constitutes 91 per cent of the labour force. As a result, the inequality of income has sharpened and though there has been poverty reduction, there are still around 300 million people who are poor and near poor. They have not benefited from the economic reforms.”

Bhide says the young middle class is restless and does not have the patience for India's traditionally slow pace of governance. It is also a group with access to a high disposable income at an early age, a factor which intensifies social disparity. This new class of consumers unlearnt everything that the older middle class had held sacrosanct. And they were not alone; they took the Indian marketer along. “Liberalisation brought in the mindset that consumption is good and, to that extent, it was the first turning point when people started saying, ‘Hey listen, greed is good’. It steered the saving mindset of the Indian to a spending mindset,” says brand consultant Harish Bijoor. “The marketer had to realise that the consumer is important. The customer had to be harvested, the customer had to be nurtured, the customer had to be mollycoddled and the customer's tantrums had to be borne with. That was a key marketing mindset change, which helped the country.”

IT IS BECOMING increasingly difficult for marketers to push things down the consumer's throat as the latter becomes more discerning. Raunak Trivedi, for instance, refuses to buy an inexpensive water-bottle and prefers a Nike bottle, never mind the cost, because its inner walls are coated with a layer of chemical to keep its contents fresh throughout the day. His grandmother Indu admits that she would have taken to technology more easily had it not been for her “middle-class mentality”.

Raunak's sister Natasha, 20, often finds herself conflicted between these pulls. “When one side speaks of the virtues of a Nike bottle and the other says it serves the same purpose as a 10-rupee bottle, I don't know which way to go because they are both correct. I try to look for middle ground,” she says.

Their mother, Sunanda, speaks of the inanity of another manifestation of consumerism—the supermarket. “I have a friend who never seems to know how much a certain article cost her because she paid for it as part of a consolidated bill without checking out the price of each individual article,” she says. Sunanda avoids shopping at malls, and would much rather pick up her stuff from Hill Road in Bandra and pair the pieces cleverly.

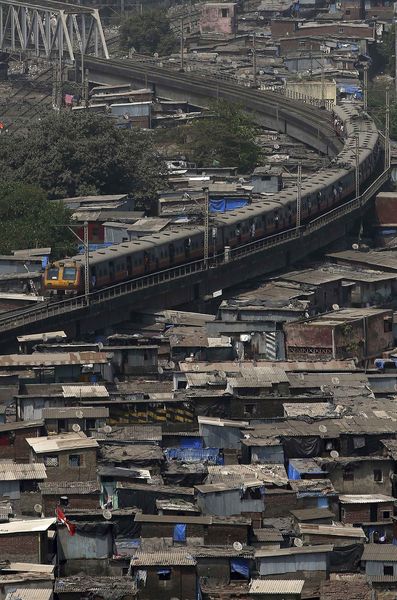

Interestingly, the streets of India have not changed much since 1991. The merchandise that Sunanda buys often coexists with people who continue to reside on the pavements. Jockin Arputham, who heads National Slum Dwellers' Federation and has been working to organise slum dwellers for around five decades, has seen Mumbai's slums proliferating exponentially as more jobs attracted more migrants to the city after the reforms. “We always had slums, but they weren't everywhere. It was only in 1995-96 that Bambai became Slumbai,” he says. Arputham laments that while we live in the information age, the disadvantaged still do not have access to the information relevant to them. He cites the example of the Mahatma Gandhi Pathakranti Yojana, a government scheme for subsidising housing for the poor which he helped draft in 1996-97. “Nobody tries to find out how many self-housing groups were formed. Every pavement dweller was supposed to get housing within five years. If people knew about this, by now Mumbai would have been cleared.”

A subject about which awareness has improved in the past 25 years, but without quite translating into action is the environment. Says Sunita Narain, director of the Centre for Science and Environment, “In the past 25 years, the world has been pushed to the edge of environmental disaster. This has been due to pursuit of economic growth at the cost of environment and the environmentally unsustainable lifestyles led by people in rich countries. Cleaner but more expensive technologies have been not used, more so in countries such as India.”

The prioritisation of economic growth has taken other casualties as well. The rise of the 'pink paper' and the increasing importance of 'shareholder value' together have almost illegitimised labour unions in the mainstream discourse. Says A.K. Padmanabhan, president of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions, “To put it in one word, the trade unions and the working class movement have been put on the defensive.” Liberalisation, he says, took away the guarantees that had been earned by decades of agitation and governments stopped paying even lip-service to workers. “Post-1991, the discourse changed from ‘downsizing’ to ‘rightsizing’,” he says.

Agriculturists have fared no better, as the reforms did nothing for them. Girdhar Patil, an expert on the agro-markets who has long been associated with the Shetkari Sanghatana in Maharashtra, sees 1991 as a missed opportunity for agricultural reforms. “If agriculture is considered an industry, the capital aspect of it is not being taken care of. Capital erosion has reached such degrees that farmers are committing suicide. There used to be a margin to keep them alive; that has been lost. If the market was open, agricultural produce would have appreciated in line with global rates. That isn’t happening,” he says. The government, indeed, has never really considered agriculture to be an industry, he says, keeping the price control mechanism in its own hands and enabling the availability of cheap labour for other industries.

Game over: Hindustan Motors, the oldest car factory in India, circulated closure notice after it stopped manufacturing the Ambassador car | AFP

Game over: Hindustan Motors, the oldest car factory in India, circulated closure notice after it stopped manufacturing the Ambassador car | AFP

That does not make for sound policy, considering that 65 per cent of India's population is engaged in agriculture and in the years ahead, India will have to rely on domestic demand-driven growth as the world slows down. Besides, India has been slow in aiding agricultural growth. “In the six years after China opened up its economy in 1978, agricultural growth shot up from 2 per cent to 7 per cent, and led to an unprecedented degree of poverty eradication,” says Milind Murugkar, a policy researcher and activist associated with Pragati Abhiyan, an NGO working on rural development. “In fact, you rarely find countries bypassing agricultural development. But in India, there has been no major technological development in agriculture since the Green Revolution.”

THAT AGRICULTURE NEEDS some work is even acknowledged by corporate consultants. “The agriculture sector is yet to realise its full potential. This is important to achieve inclusive growth and transformation,” said Akhil Bansal, deputy CEO, KPMG India. “Besides the obvious opportunity of adding value through food processing and packaging, there are several other possibilities in the areas of agri-services, farm mechanisation, post-harvest management, quality testing services and supply chain management.”

The weakening of the organised farmers' movement has also not helped. This is, in part, because of the withdrawal of the state from the function of procuring agricultural produce. “The movement weakened because it used to operate in places where there was commercial farming, along with a processing unit, and where the government was present in a big way to procure goods. It was thus easy for farmers to pressure these agencies for prices,” says Murugkar. With no face to agitate against, farmers' resistance naturally withered away.

Poor show: Mumbai's slums proliferated exponentially after the reforms | AP

Poor show: Mumbai's slums proliferated exponentially after the reforms | AP

The withdrawal of the state as a consequence of liberalisation rankles elsewhere, too. Mantu Das, 58, has a few months left to retire from the company he worked for more than 40 years. But he would not get a grand send-off because the company, Hindustan Motors, recently closed down its main operation in Kolkata. Mantu last year was asked not to come to his office at Uttarpara, on the outskirts of Kolkata.

The oldest car factory in India, Hindustan Motors circulated closure notice after it stopped manufacturing the Ambassador car, its pioneering work in the fifties. The B.M. Birla company built the factory before independence. Later, a township came up around the factory which employed some 25,000 workers till the late eighties. But the economic reforms changed the fate of Hindustan Motors—it lost its shine within years. The Ambassador was no longer a pride of Indians. Hindustan Motors tried to diversify but could not survive the changing environment. It started losing its share of the market in the nineties and the closure happened in 2014.

MANTU, ONE OF the oldest employees in the company, has seen workers leaving every year. “After closing down they assured us that they would give us Rs10 lakh as compensation. But we have received only Rs1 lakh yet. I don’t believe they would pay us,” he says. However, he does not believe that Hindustan Motors lost out in competition. “Hindustan Motors was destroyed by the management with the help of political forces in Bengal,” he says.

Another of India's industrial flagships, Hindustan Machine Tools, is on the brink. The future is bleak for its watch factories; many of them await a shutdown. The government may continue to keep the watches division alive by taking orders for customised watches. Currently, the watch factories at Tumkur and Bengaluru in Karnataka are functioning but with only a few workers and limited operations. “Many companies put in bulk orders for customised watches. I feel better marketing of HMT watches could have saved the brand. The quality and skill set of our workers are exceptionally good,” says Veerana Gowda, who had worked in the HMT watches division for more than 25 years.

An employee at the HMT factory in Bengaluru says about 1,200 workers are still working in the watch factories in Tumkur, Bengaluru and Ranibagh near Nainital in Uttarakhand. A final voluntary retirement scheme has been announced by the government but the workers are yet to get the details. “Most of the workers are happy after the government announced a VRS scheme but a final reaction can come only once they receive the details of the scheme,” says Girish Kumar, acting chairman of the HMT watches factory in Tumkur. As the former time keepers of the nation stare at a bleak future, it seems Indians are going to miss the fine watches they make.

Indians, it seems, are missing many things. Rediff's Balakrishnan says that the average monthly internet bill should have been no more than Rs100 if the government had done its bit to improve connectivity by laying underground optical fibre. “The infrastructure to transmit internet needs to be created and only governments can do that. The payback period is 20 to 25 years when you put fibre and you need fibre; you can't do things by spectrum, contrary to what people imagine,” he says. He attributes the state's inability to discharge such duties to resistance from the elite, who do not like excavators moving in their localities, and the media, which reflects their views.

Narrowing gap: Post-reforms, more Indians started taking to the skies | reuters

Narrowing gap: Post-reforms, more Indians started taking to the skies | reuters

In fact, Tushar Trivedi remembers a more comfortable time when the state was a more palpable presence. “The market-driven economy is also disillusioning because earlier, the state's services were of a high quality. Electricity charges were low. Basic living was affordable. Today, even that has gone beyond the limits of affordability. And this change has happened in my lifetime, that too between the time I went from being a student to a professional,” he says.

Bhide of TISS says the poorest have been hit harder. “The term 'social sector' emerged through the reforms, which gave precedence to the economic and created a class of people who were becoming more destitute,” she says.

THERE IS, HOWEVER, consensus that India needs more reforms, though whether they should be of the 1991 kind is debatable. ORF's Sengupta suggests that the next phase should come from the states. “Much more focus is needed on agriculture, labour laws, health care, quality of education, financial services and infrastructure. The quest for financial inclusion should have been started much earlier. Greater allocation of federal funds to the states on these accounts has been made over the years, but the performance has been varied. It is up to the states to implement agricultural, health and education reforms as these are state subjects,” he says.

Reforms, in fact, are an ongoing process and some key reforms are still pending. “Implementation of the unified tax system—GST—is expected to increase the GDP by 1 or 2 percentage points, while easy land acquisition and labour norms are likely to improve the business condition,” says Bansal of KPMG.

For the time being, Indians will continue to be delighted and oppressed by the effects of the Great Indian Liberalisation of 1991 at the same time. What comes up repeatedly through the voices of many people is an acute awareness of figures, objects, and prices which, unlike before, keep tending to infinity. As Indu Trivedi says, “Giving was my pleasure. But now my ability to do so has shrunk as I can never be sure how much will be enough for her,” pointing to her granddaughter.

But then, that is the nature of the market—a huge, formless entity which everybody is a part of and which nobody understands.

WITH RABI BANERJEE AND ABHINAV SINGH