Do you know what the word kameena means?' my teacher asked me.” The audience seemed to sit up as former bureaucrat Ashok Thakur uttered the Hindi imprecation in the seemingly inappropriate setting of a national-level conference on human resources. “'It comes from kameen—someone who works with his hands,' he said. That is what we think of people who work with their hands,” Thakur explained. With audible 'tch-tch's, the audience acknowledged India's culture of devaluing manual labour, thereby incurring the karmic load of remaining a laggard in the manufacturing sector.

Months later, when I emailed Thakur asking him if he saw this cultural prejudice impeding the progress of the government's skilling initiatives, especially in rural areas, he replied, “In fact, this attitude prevails more in the rural areas as these are the bastions of the caste system, which has been responsible for perpetuating the stigmatising of manual labour through the ages. Unless this is done away with by our society at large, it will continue to be a serious stumbling block in our efforts to skill India, be it PMKVY [Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana], DDU-GKY [Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana] or any other scheme.”

A more explicit connection between the caste system and India's lack of skilled labour comes from Santosh Mehrotra, professor of economics at the Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, who led the drafting of the National Vocational Education Qualification Framework (NVEQF), now known as the National Skills Qualifications Framework (NSQF). “We have Brahminical values running right through our education system,” he said. “This had implications.”

This state of affairs ensured that all attempts by the government to skill large segments of the population remained ineffective. Mehrotra said the first serious attempt at offering vocational education at the school level was made in 1975. In 1986, vocational training was offered to students of classes 11 and 12. Both the schemes failed because they were envisaged for the poorest of children and there was never any aspirational value associated with them.

The fallout of such a legacy is becoming increasingly evident. In April, securities house Ambit Capital released a report titled Sizing India's Demographic Bomb. Pitting ten northern states against their south Indian counterparts, the report stated: “Economic theory suggests that when the proportion of young people in a region increases, a significant boost to economic growth should materialise. The post-World War II years saw the west in general and the US in specific benefit from this dynamic as the baby boomers delivered record productivity.... Even as India's demographic profile today is similar to that of the US in 1960, contrary to popular belief, a demographic dividend is unlikely to accrue to India anytime soon.”

Bad policy management did its bit to aggravate matters. “The silent bureaucratic turf war that goes on in government is often responsible for conflicting regulations, leading to loss of momentum and dissipation of any long-term vision,” said Thakur. But soon, Delhi's mandarins were “realising the serious threat of the demographic dividend turning into a demographic nightmare” and that translated into a series of steps in the Eleventh Five Year Plan. The National Skill Development Mission was set up in 2008, as was the National Skill Development Coordination Board. The National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) was set up as a public-private partnership, with industry associations accounting for 51 per cent of its capital base. Efforts within the HRD ministry to align education with skills began in 2010 and resulted in the formulation of the NVEQF. When the NDA government took office in 2014, it created a separate ministry for skill development and entrepreneurship. The following year, this ministry notified a framework called the National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, which envisaged a nationwide mission to skill 40 crore people by 2022. Industry was sought to be engaged through sector skill councils (SSCs), which would define curricula for skilling in each sector.

A year on, 36 affiliated SSCs are listed on the ministry's website. A state- and sector-wise listing of training centres is available on the NSDC portal. Partners can choose to borrow from the NSDC at a 6 per cent interest rate. But, many of the centres listed on the site are operated by organisations that have long been running training programmes and share a non-financial association with the NSDC. In other words, the NSDC is lending its brand to these entities to help enhance their credibility. To what extent that is useful remains a question.

“When a construction company has to hire 500 workers, are they looking for NSDC-certified workers or are they going for the next person available?” asked Ninad Karpe, managing director and CEO at Aptech, one of the training partners. He said though people are not looking for NSDC-certified workers now, it would happen as the NSDC brand is getting built gradually.

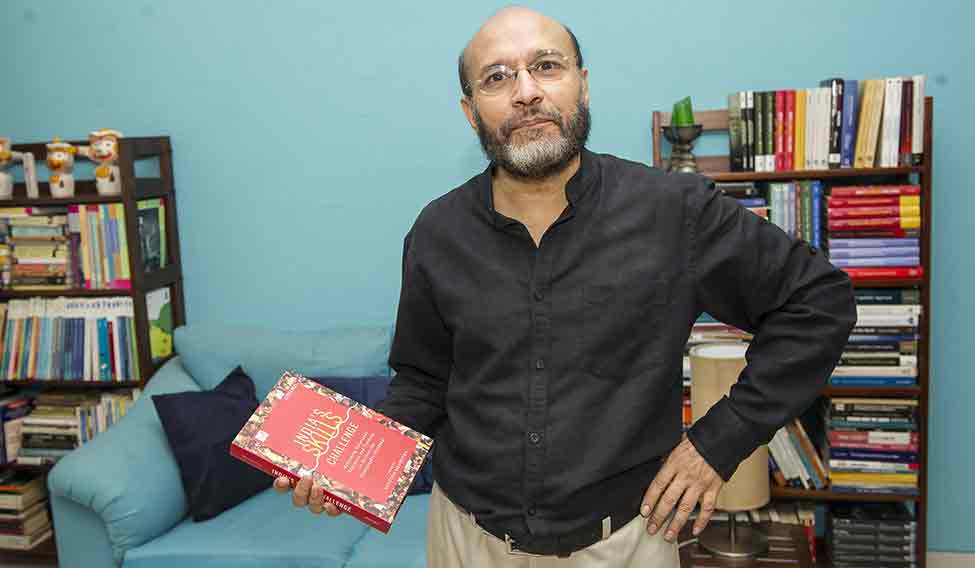

Company policy: Santosh Mehrotra of JNU says the private sector will have to take ownership of the skilling initiative | sanjay Ahlawat

Company policy: Santosh Mehrotra of JNU says the private sector will have to take ownership of the skilling initiative | sanjay Ahlawat

Evidently, there are no fresh capacities being created and the training partners are leveraging their existing infrastructure to implement the programme. To be fair, the programme was effectively launched only a year ago and is far from achieving many of its stated objectives. Yet, there is much to worry about. For one, there are no centres in West Bengal and the seven northeastern states.

The experience of other skilling schemes also yields useful insights. The DDU-GKY requires project implementing agencies (PIAs) to adhere to a set of guidelines defining everything from the dimensions of the building where training is imparted to the mode of payment to be offered by an employer. Despite this, the scheme offers no answers to some of the challenges the Indian hinterland is throwing up.

The Indian youth is now growing increasingly averse to the idea of migration. Sanjeev Srivastava of CL Educate, a PIA, said, “These guys [trainees] don't want to move. And it's not just peer pressure; even the parents are not willing to let them move.”

T. Muralidharan of TMI Group, an NSDC partner, said, “My reading is that many people get skilled and stay on at home, or they find a job unrelated to their skill. The investment from skilling will yield fruit only when people stay in that field for some time and succeed and then make money.”

PIAs are also expected to place the people they train—a function well beyond their core competency. “Basically, our job is training and making them ready for placement. We cannot create opportunity in the market,” said N.K. Shyamsukha of ICA Edutech, another PIA.

But a far more pernicious development might be destroying the very incentive for skilling—the narrowing of the skill premium. [The skill premium denotes the difference between the wages paid to skilled workers and those for unskilled workers.] A year and a half ago, Muralidharan studied the wages stipulated by the Maharashtra government and found the gap between the wage for the unskilled and that for the semi-skilled to be about 5 per cent, which is inadequate, he said.

S.K. Sasikumar, senior fellow at Noida's VV Giri National Labour Institute, however, said, “If you are a skilled person, do you think you will walk into a labour market outcome which does not compensate you well? You might prolong the wait for a job. But you will not accept a job with very low remuneration because of your aspiration.”

In a corner of Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh, though, an implementer seems to be saddled by fewer problems. Rajeev Jain jauntily showed us around the place near the city's Jain Degree College, describing how most implementers struggle to create the kind of infrastructure that he offers. Jain set up the centre in the early 1990s as a franchisee for NIIT and now uses it to provide training under DDU-GKY for ICA Edutech. He runs classes in IT skills and soft skills for 25-student batches and ensures meals for them at lunchtime. He also takes care of placements. Given the centre's reputation, attracting trainees was not an issue, he said.

Jain, however, said problems crop up after placements. Two of his boys had been placed at the outlets of a leading quick-service restaurant in Dehradun. Despite being entitled to a stipend for being placed away from home, the two came back in a matter of months.

Fatima, who travels to Jain's centre from Malipur every day, tells us chirpily that she would be doing this even if there were no stipend for the training. And yes, she will be happy to leave home for a job.

Trouble is, there may not be too many jobs within the limits that Fatima's family may define for her. This, and not the quantum of people to be skilled, is what we should be worried about, said Mehrotra. Things are complicated further by both policymakers and employers who continue to stereotype women at work, and make no effort to make workplaces more conducive for women. The Ambit Capital report identifies this skewed gender ratio in the workplace as one of the reasons for the economic backwardness of northern India and states that for every 100 people in the ten states, 36 fall in the age group of 15 to 35 years. Only 17 of these 36 are women.

Till a few months ago, India had a scheme called the Priyadarshini Programme, launched by the UPA government. The programme envisaged “holistic empowerment of 1,08,000 poor women and adolescent girls through formation of 7,200 self-help groups.” Training was to be a key component of the programme. On April 28, Women and Child Development Minister Maneka Gandhi announced the closure of the programme in the Rajya Sabha. “It was a very bad programme,” she said. “031 crore had been spent with no work on the ground. So the ministry decided that what has been wasted was wasted and the rest of the funds were returned.”

No alternative programme has been announced.

The most stinging indictment in India's skilling story is reserved for the private sector. Experts say that while the NSDC was supposed to draw 51 per cent of its capital base from industry associations, the latter set washed its hands off the matter after making an initial infusion. Questionnaires emailed to Assocham, CII and Ficci elicited no response. A query on CII's contribution sent separately to Aptech's Karpe, who is also deputy head for the confederation in the western region, went unacknowledged, too.

One other way in which the private sector has discouraged skilling is by normalising the hiring of contractual labour in large numbers. “Around one-third of manufacturing is contractualised and that hiring is taking place at a very low wage. Obviously, you are not getting people with skill sets there. Lack of skill sets can adversely affect productivity. That way, private industry itself is compromising on productivity,” said Sasikumar.

What, then, should India be doing to upgrade its skilling initiative? Answers can be found in the experience of other economies, especially those of Brazil and China. “The private sector will have to take ownership of the skilling initiative, and ownership comes only when it puts money into the system and that money comes straight back to them,” said Mehrotra. This can be executed if the government were to impose a tax on large and medium enterprises and the money were to be aggregated in the form of sectoral funds.

He wants Indian industry to realise the importance of something former Planning Commission member Arun Maira once wrote, about people being the “core asset” of industry. Mehrotra said, “Human beings, workers are the only 'appreciating asset' that industry has. But you appreciate in value only when someone invests in you, right?”