In February, Major Satish Dahiya, 31, died fighting militants in Kashmir’s Handwara town, but not before killing Abu Darda, a top Lashkar-e-Taiba commander. An officer from 30 Rashtriya Rifles, Dahiya was awarded Shaurya Chakra—India’s third highest peacetime gallantry award. But the recognition came too late. While he was alive, Dahiya, like most in his cadre, did not get his due—all because he was an officer from the Army Service Corps (ASC). [Dahiya’s wife, Sujata, will be appearing for the Service Selection Board examination later this month.]

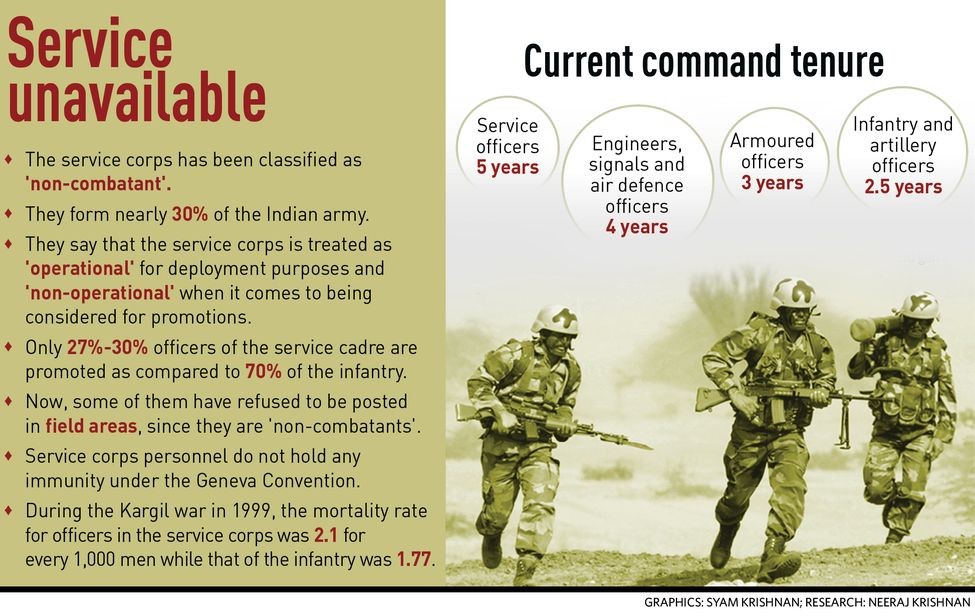

Nearly 70 per cent of the officers of Rashtriya Rifles, the main counter-insurgency force of the Army, are from non-infantry that includes the services corps. The services corps provides logistics support and is made up of the ASC, Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (EME) and Ordnance Corps. The services corps, comprising nearly 30 per cent of the Army, has been classified as ‘non operational’, thereby denying its men the monetary and promotion benefits that combat arms corps cadre get. This, despite the fact that many of its officers have been trained in infantry units and are part of counter-insurgency operations. The classification, therefore, has divided the world’s third largest army, with the discord now turning into a legal battle.

The term ‘non operational’ was first used by the Army in its affidavit to the Supreme Court last year on, what services corps officers call, the Army’s “discriminatory” promotion policy. Angry, services corps officers are now refusing to accept operational field postings, including those in forward and counter-insurgency areas—an unprecedented move in the disciplined force. This October, Major Amod Kumar, Major Shubhankar Mishra and Sepoy Prahlad Singh filed a petition in the Supreme Court against the Army Headquarters for deploying them in operational areas but denying them any combat corps benefits. Kumar is with the 44 Rashtriya Rifles and Prahlad with the 4 Rashtriya Rifles in Kashmir, whereas Mishra is posted in a field formation in Rajasthan.

Lt Gen A.K.S. Chandele, former director general, EME, told THE WEEK: “It is a very sad situation. Young officers from the services refusing to go to operational areas is a symbolic fight. They are basically fighting for their pride.”

With the rift widening, the military top brass held a special meeting during its commanders’ conference at the Sena Bhawan on November 6 to chalk out an amicable solution. The Army also came out with a statement: “The anguish amongst some personnel on discrimination in their status needs to be put to rest and the chief of Army staff [General Bipin Rawat] has assured that necessary corrections, where needed, will be addressed.” On November 20, Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, too, held a meeting with the three service chiefs to discuss the promotion policy.

The Army’s 2009 ‘command exit promotion’ policy, based on the A.V. Singh (former defence secretary) Committee report, was first challenged by ASC officer Lt Col P.K. Choudhary, who found that the promotions were skewed in the favour of the infantry and artillery divisions. The Indian Army consists largely of 11 streams—infantry, armoured corps, mechanised infantry, artillery, air defence, engineers, signals, ASC, Ordnance, EME and other corps including intelligence and aviation. The first three streams are loosely grouped as ‘combat arms’; the next four as ‘combat support arms’; and the ASC, Ordnance and EME as ‘combat services’.

The promotion policy provided for a command tenure of 2.5 years for infantry and artillery officers, 3 years for armoured officers, 4 years for engineers, signals and air defence officers and 5 years for services officers. The disproportionate period of tenure had a direct effect on the vacancies and promotion avenues, thereby creating discrimination and batch disparity.

In 2009, Choudhary, who has served with the Rashtriya Rifles and other operation units and also at Siachen, filed an RTI application, which was denied on confidentiality grounds. On filing an appeal, he received some information, but he wasn’t convinced. So, he filed a case at the Armed Forces Tribunal, challenging the promotion policy. In 2011, he wrote to Army chief V.K. Singh and later successive chiefs. Choudhary said the infantry and artillery divisions were allocated an unfairly large number of promotion vacancies at the rank of colonel. (The tribunal quashed the promotion policy in March 2015, saying it violated the right to equality. It was later challenged by the Union government in the Supreme Court, which upheld the policy but asked the government to create 141 additional vacancies to the rank of colonel for combat support officers who had joined the force between 1992 and 1997).

According to the services corps, only 27 to 30 per cent of its officers are promoted, whereas 70 per cent of infantry officers get promoted. In a letter to the defence ministry, outraged officers said institutionalised discrimination was made feasible because the last nine Army chiefs were from the infantry and artillery cadres.

Also, all commissioned officers were earlier recognised as combatant officers and they represented the various specialised components of the Army that make it a diverse yet cohesive fighting unit. Even now, they all have common entry and training and are to be treated by the enemy as one entity under international laws in the event of war.

But as Major Mishra pointed out in his petition, “As non operational members of the Army who are not required to operate under combat conditions, they are not entitled to bear arms or engage any enemy in any international or domestic armed conflict. As such they are deemed non combatants....” Quoting the Geneva Convention III, Article 4 A (1), which has an international bearing on their employment and treatment in war, Mishra stated that at the cessation of hostilities only a legitimate combatant will be safeguarded from prosecution for acts of war committed during the course of the armed conflict. “Therefore as per the existing legal situation, the petitioner and other members of the services cannot be employed in any external offensive action by the respondents without peril to the former’s safety and dignity, as distinct from the rest of the components of the regular Indian Army,” his petition read.

The families of the officers, too, have joined the fight for rights. Kumar’s wife, Anjali Priya, wrote to Sitharaman in September: “We are not ready to lose our husbands under this state of ‘indignity’.” In his letter to the defence minister in November, D. Panda, father of Lt Colonel Prasun K. Panda, wrote, “How can my son [an ASC officer] be non operational when he has injuries and metal splinters till date? You give dignity when they die, but what about dignity when they live?” Panda was injured during an operation in Manipur in 2003.

According to the services corps, its mortality rate in the Kargil war was 2.1 per 1,000 men, whereas the infantry’s mortality rate was 1.77 per 1,000 men. Seven ASC officers were martyred in Kargil. It is ironical that the combat services officers were denied vacancies that were churned out of the Kargil experience, that too on a false averment that called them non operational.

Advocate Neela Gokhale, who is representing the services officers in the Supreme Court, said the A.V. Singh Committee clearly stated that only the age profile of unit commanders in operational units was to be brought down, and the services corps was not part of it. So, the ministry of defence cannot deploy them in operational areas. If it did, then it cannot deny them promotion benefits. “You cannot tweak the policy as per your convenience. That is why people are refusing to go on operational postings,” she said. On December 11, at the Supreme Court hearing of the case, the Army sought four more weeks to respond. The court, however, gave the Army a two-week deadline.

A defence source in the South Block said, “The role and duties of the services and combat arms unit are not comparable in a contact battle scenario, and [therefore] the A.V. Singh Committee recommended that the commanding officer of the ASC unit can have a comparatively higher age profile than that of a combat arms unit [officer].”

Lt General (retd) Arun Malhotra, who served as director general of ASC, said “The issue should have been resolved in-house. There should not be any discrimination in the Army over combatant title. But I am told the top leadership of the Indian Army is seized of the matter and is looking forward to resolving it at the earliest.”