A participant carved F57, the name of the group, into his arm.

A participant carved F57, the name of the group, into his arm.

I was a little apprehensive when I called up a friend, a cyber security expert of global repute, on August 19, 2017. Google had alerted me that someone from Kiev in Ukraine was attempting to log into my mail system.

“It could be a phishing attempt,” said my friend. “Hackers could already be in possession of your confidential information. You should change your password immediately.”

For good measure, I also deleted my account in Vkontakte, the Russian social media giant, where I had spent the past few weeks trawling through the accounts of suicidal teens. I was on the trail of the deadly Blue Whale Challenge, a series of tasks that apparently results in the player committing suicide. One Reddit user posted a list of 50 challenges to be completed in 50 days, the last challenge being suicide.

I had a sneaking suspicion that the login attempts originated from unscrupulous users I had communicated with. It was reported that the masochistic challenge originated on Vkontakte, whose administrators later removed all links to the game.

The Blue Whale Challenge had become a talking point with the deaths of 17-year-old Rina Palenkova of Russia in November 2015. Later, fear over the challenge spread to India.

But, was it actually a “snuff game” that targeted emotionally vulnerable teens on the internet, manipulating and coercing them to their deaths? Was it, as reports suggested, just an online community of the mentally ill and the suicidal? Or was the whole thing an urban legend, warped by an overzealous media and technology novices who couldn’t tell a mobile phone from a soap box? The reality seemed a lot more nuanced.

In design, Vkontakte is like a minimalistic Facebook, with features like adding friends, posting status updates and sending private messages. Delving into the depths of my poetic vision, I came up with a username, ‘Love is a Lie’ and a maiden post “I want Blue Whale”. According to the rules of the challenge, I had to wait till an administrator of the Blue Whale community judged me insane enough to grant entry. Once entry was gained, there would be no opting out. According to reports, the administrators would threaten to leak private information about defectors into the dark web and to physically harm their family.

My compadres, all awaiting entry into the community, had posted colourful requests, which reflected a whole gamut of feelings, ranging from false bravado to contagiously depressive emotions. I admit I got—to appropriate teen lingo—“punk’d” more than once. Barely a few minutes after I posted my message, unknown user Danny Schiff appeared in my chat box.

Danny: Need a tutor?

Me: Yes.

Danny: Why do you want to do the challenge?

Me: I want to see how long I can fall without hitting the ground.

I never heard from him again.

Undeterred, I chatted with a host of other members. Ultimately, user Kabir (name changed) emerged a saviour, sending me the link to the profile of one A.A. who, he assured, was an administrator and would induct me into the game. I messaged him/her/bot and the long-awaited reply came: Do you want to play? Within a few days, her account was deactivated.

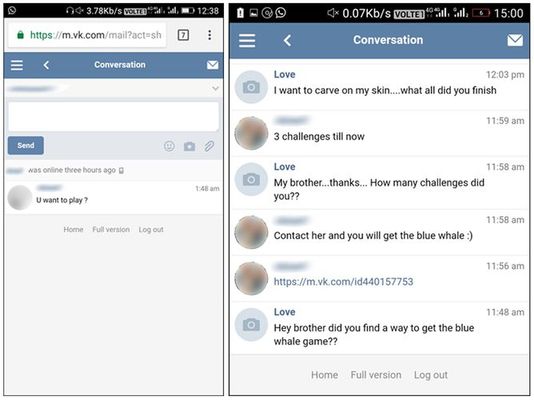

Bloody task: A curator’s question to the reporter; (right) A Conversation with the participant.

Bloody task: A curator’s question to the reporter; (right) A Conversation with the participant.

The key to understanding the challenge was in the last place anyone would think to look—pop culture symbolism. The profile picture of A.A. looked suspiciously like that of a “Death God” in the Japanese manga Death Note, where the protagonist is consumed by the idea of cleansing humanity of criminals and filthy elements. Ring a bell? The entire challenge mirrored the storyline of the 2016 film Nerve, in which an online game of dare, moderated by a group of invisible administrators, escalates to deadly proportions. The name Blue Whale, while widely considered a reference to the phenomenon of a beached mammal, has also been connected to the lyrics of the song ‘Burn’ by the Russian rock band Lumen. One of the more popular hashtags of the community, “Wake me up at 4:20”, is a lurid reference to 4/20, or April 20—a day of literal celebration for marijuana smokers across the world.

And the suicides? Would it be so far-fetched for a depressed person to consider suicide in this age where mental illnesses are romanticised? Case in point, guitar legend Jimi Hendrix. Or the psychological tendency of copycat suicides? After the death of actress Marilyn Monroe on August 5, 1962, reports had cited a 12 per cent spike in suicide rate. Rockstar Kurt Cobain’s death on April 5, 1994, had sparked a suicide crisis and prompted studies on the topic. The copycat suicidal tendency was brought under the umbrella of “Werther Syndrome”, named after the protagonist in Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther. After the novel was published in 1774, a number of suicides modelled after the plot of the book were reported.

The community members of Vkontakte appeared to be the prime candidates for suicide. I asked Kabir about the challenges. How many did he complete? Four. Was there any self harm? Unsolicited, horrific images of a bruised arm with F57 branded into the skin arrived. Anything else? Yes, watching a scary movie at midnight. New mission? Silence.

“Not allowed to tell,” he said.

Then, I prayed. That he was nothing more than a very convincing bot; you know, like in the movie Her.