As the clock struck 1:30pm on May 10, a shrill ring pierced the U-shaped office of Lt Gen Rajiv Ghai, the Army’s director general of military operations (DGMO), at South Block in New Delhi. The call came on a designated hotline―manned 24x7―for instant, uninterrupted communication between the DGMOs of India and Pakistan. On the other end would typically be Maj Gen Kashif Abdullah, Ghai’s Pakistani counterpart.

Normally, such calls take place on Tuesdays, serving to inform and coordinate routine military affairs. But this was no routine Tuesday. For the past three days, both militaries had been engaged in intensive operations involving fighter jets, missiles, drones and heavy artillery―triggered by the April 22 massacre of 26 civilians at Pahalgam in Kashmir by Islamabad-backed terrorists.

India had launched Operation Sindoor and Pakistan responded with Operation Bunyan Ul Marsoos (Iron Wall). When the call came, Ghai was unavailable, attending a meeting. The follow-up call came at 3:35pm, carrying a ceasefire offer. Islamabad had blinked first.

By that point, India had already secured its strategic objectives―military, political and psychological.

On the night of May 6-7, India had precision-struck nine key terror hubs across Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) and deep inside Pakistan. New Delhi emphasised that the fight was not against the Pak military, but against terror. Pahalgam was a real escalation, it maintained; the counterstrikes were not.

The operation demonstrated that India had the capability to strike at will anywhere in Pakistan, even when its military was on high alert. Pakistan’s retaliatory wave of drones and missile attacks was neutralised.

“India’s shield of sensors, missiles and jammers protected the airspace from Jammu and Kashmir to Gujarat as Pakistan fired a swarm of drones and missiles,” said Maj Gen (retd) Jagatbir Singh, distinguished fellow at United Services Institute of India. “Incoming threats were identified, tracked and neutralised by India’s Integrated Counter-UAS Grid and Air Defence systems.”

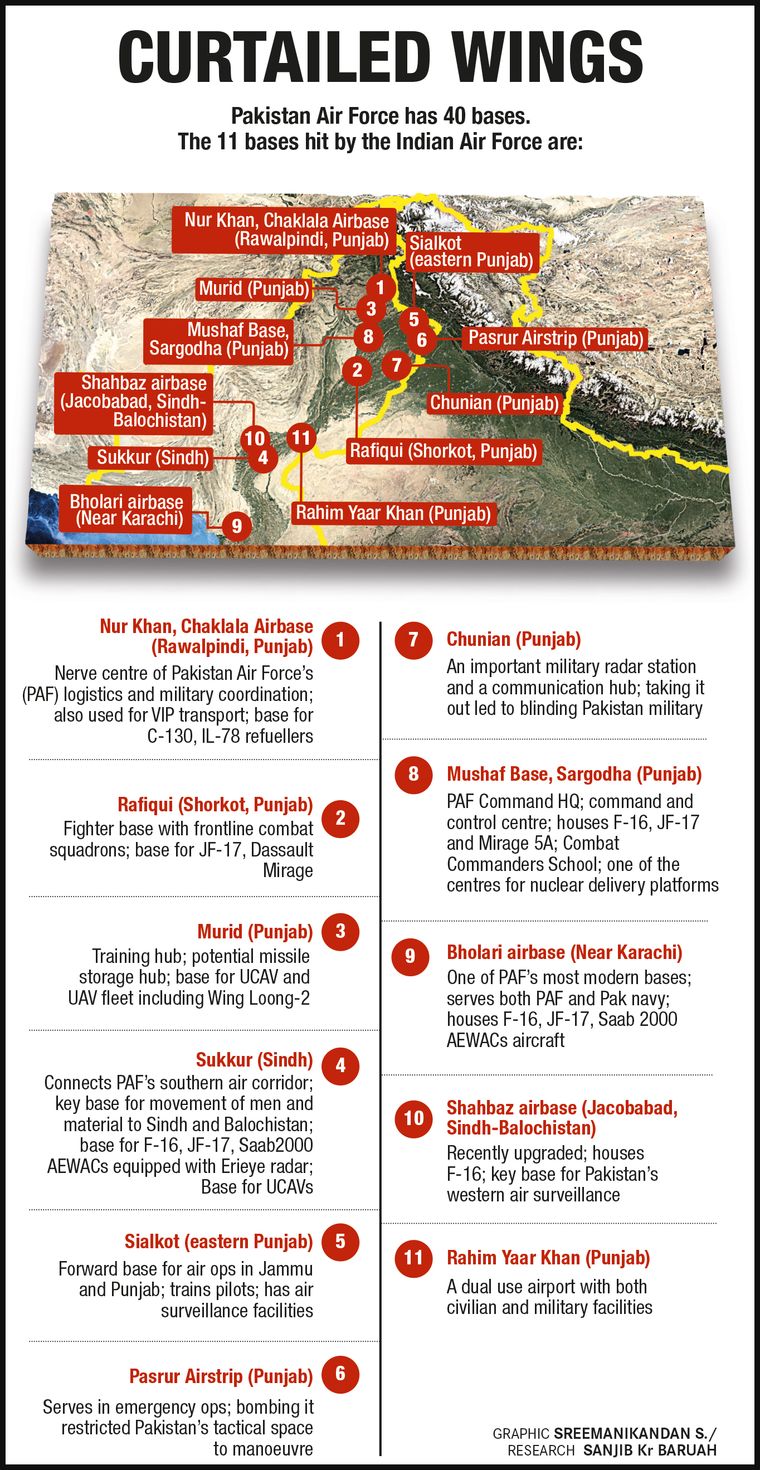

India responded by carrying out precision strikes on major Pakistani airbases―including Chaklala, near Rawalpindi. Though the government has not officially confirmed the use of the nuclear-capable BrahMos in its conventional mode, the scale of destruction, especially to military runways, strongly indicates it.

“The strikes showcased the evolution of modern warfare and the ability of Indian forces to carry out precision strikes using high-technology weapon systems,” Singh said. “The sheer scope, range and intensity have changed the matrix.”

India’s political objectives were achieved. The Pahalgam attack provided grounds for New Delhi to place the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance, sending a message: the cost of sponsoring terror would rise inexorably.

In the past few years, India has made a strong case to revise IWT, signed in 1960 and based on outdated engineering practices. Climate change, melting glaciers, rising energy needs and demographic shifts made a compelling case to revisit the treaty.

“Clearly, there is a case for looking at the distribution of rights and obligations under the treaty,” a top government source told THE WEEK. “We approached the Pakistanis for precisely that, but for the past two years they have been stonewalling. This stonewalling is, in some sense, a violation of the treaty.”

Psychologically, Operation Sindoor delivered a jolt. It was India’s deepest strike inside Pakistan since 1971, and India demonstrated that it can reach terrorists and their backers anywhere in Pakistan. There was no safe haven left.

“The impact will be profound and deterring,” said Lt Gen (retd) Rakesh Sharma, distinguished fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS) and at the Vivekananda International Foundation (VIF). “We are no longer going after small camps here and there. We will go for the jugular.”

Even before the DGMOs spoke on May 10, President Donald Trump―in his typical mercurial and unpredictable style―took to social media to claim credit for brokering a ceasefire. “After a long night of talks mediated by the United States, I am pleased to announce that India and Pakistan have agreed to a FULL AND IMMEDIATE CEASEFIRE,” Trump posted.

He also offered to mediate on Kashmir. “I will work with you both to see if, after a ‘thousand years’, a solution can be arrived at concerning Kashmir,” he said.

India’s stand, in accordance with the provisions of the 1972 Simla Agreement, has been to not allow external or third-party intervention on Kashmir. Its official position remains unchanged: the only pending issue is the return of PoK.

Yet Trump doubled down. During his visit to Saudi Arabia on May 13, he repeated his claim: “Just days ago, my administration successfully brokered a historic ceasefire to stop the escalating violence between India and Pakistan, and I used trade to a large extent to do it.”

India’s ministry of external affairs issued a quick rebuttal. “After Operation Sindoor commenced, US vice president J.D. Vance spoke to Prime Minister Narendra Modi on May 9,” said an MEA official. “US Secretary of State Rubio spoke to our external affairs minister on May 8 and 10, and with our national security adviser on May 10. These were all conversations on the evolving military situation…. There was no reference to trade in any of these discussions.”

With the US president’s pronouncements grossly undermining India, it was clear that our well-accomplished military success was being hijacked. The question: was Trump’s claim just impetuous, or a calculated move?

The same week, Trump struck a trade deal with China, cutting tariffs on Chinese goods to 30 per cent from the peak of 145 per cent. China reciprocated with a 10 per cent tariff, down from the earlier 125 per cent. Meanwhile, trade talks with India remained stalled, with US commerce secretary Howard Lutnick attributing it to the “complexity” of covering all 7,000 tariff items under negotiation.

A more serious concern is the US threatening secondary sanctions on Russia if the latter does not agree to a ceasefire in Ukraine. Given India’s reliance on Russian energy, such sanctions could hit India hard.

President Trump’s eager positioning to mediate between India and Pakistan may be driven by the fear that China may try to fill that geopolitical space. A close relationship between India and China can strengthen the BRICS platform―a bugbear for Trump. BRICS can be undermined only when India and China remain at odds.

In this backdrop, it is not just drones and missiles that start or end wars. Rather, it is deeply intertwined strategic business interests that use both war and peace to propagate hegemony―in this case the US led by Trump.

The India-Pakistan conflict has an interesting subtext.

On April 9, just days before the Pahalgam attack, a high-level US state department team landed in Islamabad. Among them was Eric Meyer, senior official of the US state department’s bureau of south and central Asian affairs.

This was part of a US push to secure critical minerals for its advanced technologies and entrench its economic footprint in South Asia―part of Trump’s ‘resources-for-peace’ approach. At the talks table was Pakistan’s army chief Asim Munir, who spoke not just about security, but minerals as well.

“Critical minerals are the raw materials necessary for our most advanced technologies,” Meyer said at the Pakistan Minerals Investment Forum. “President Trump has made it clear that securing diverse and reliable sources of these materials is a strategic priority.”

The US is now working with Pakistani officials and international partners to invest in and manage the country’s mineral wealth―lithium, copper and rare earths. Munir’s involvement signalled that the US plan to secure a foothold in Pakistan’s untapped resource base has the backing of the Pak military.

On May 10, exactly a month after those discussions, the Trump administration rang New Delhi and Islamabad to hurriedly set the narrative of America brokering the ceasefire. The clincher came when Trump said he was ready to trade with both Pakistan and India, and hinted that Pakistan has agreed to American terms―open trade and dialled-down hostility with New Delhi. The framework for Washington’s mineral diplomacy had been complete, winning a battle against potential competitors without an actual battle being fought.

“What I am concerned about is how quickly the terror facilities in Pakistan have been brushed under the carpet,” said Tara Kartha, director, CLAWS, who was formerly with the National Security Council Secretariat. “Even more quickly, the narrative has shifted in Washington from terror to trade, which only reflects what has being going on under the Trump administration.”

What Islamabad and Washington possibly did not anticipate was how strongly India would react. “The selection of the targets and the amazing restraint that was shown has displayed our military prowess and strategic messaging,” Kartha said.

As much as 80 per cent of Pakistan’s military imports are tied to Chinese credit. Therefore, the prospect of US arms sales to Pakistan is bleak, unless countries like Saudi Arabia help subsidise purchases―a scenario that looks improbable now. With its garment and cotton industry already eclipsed by Bangladesh, and its weaknesses in pharmaceuticals, chemicals and services, Pakistan seems to have limited trade potential. Trump’s tactics have therefore provoked comparisons with the US approach to Ukraine, where minerals and resource access has played a defining role.

The American eye seems to be on Balochistan, which has massive copper and gold deposits. “Rich in natural resources and strategically located next to Iran, Balochistan offers a geographic advantage that few other regions can match,” said a senior strategic expert in New Delhi.

For the US, a presence in Balochistan would not only allow close oversight of Chinese activities in Pakistan, but also place it within striking distance of Iran’s Bandar Abbas port. “A foothold would give US strategic leverage over key shipping lanes and energy routes in the Gulf,” added the official.

For Munir, the US foothold in Balochistan can serve two purposes―stave off threats from insurgent groups and secure the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), helping feed the starved Pak economy.

“The US is using Pakistan to keep Chinese interests at bay,” said Kartha. “This conflict has forced Pakistan to bend.”

New Delhi may need to take a hard look at its relationship with Beijing in this backdrop. India’s trade relationship with China has only grown despite military tensions and diplomatic stand-offs. Over the past 10 to 15 years, the two economies have become intertwined through complex supply chains, and even as India talks of self-reliance, the reality is that certain technological and industrial dependencies on China remain. “We need to look at our interest in trade and their business interest as well,” said M.V. Rappai, China analyst at the New Delhi-based Institute of Chinese Studies.

With China emerging as a hub of artificial intelligence, drone technology and space research, New Delhi cannot ignore Beijing’s growing role in shaping future economic and security architectures. “Wars are increasingly driven by innovation rather than sheer military strength,” Rappai said. “India must take stock of these developments and assess its own capabilities.”

Also Read

- Media, missiles and mistrust: Lt Gen D.S. Hooda (retd)

- Operation Sindoor was also a DRDO and Indian industry success story

- India’s new doctrine is based on sound homework

- BrahMos: An unparalleled weapon

- 'General Asim Munir could attempt a coup or bring Islamist parties to power': M.J. Akbar

- 'India-Pakistan dialogue needs revival and a fresh agenda': K.C. Singh

Also, triumphing over Trump may not be as difficult, as American adventures on foreign soil have been riddled with missteps. The post-9/11 War on Terror in Afghanistan being a case in point. According to K.P. Fabian, former ambassador to Qatar, Beijing can trump US interests this time, as China is actively pursuing its interests in mining and oil exploration.

“Beyond minerals, Beijing sees strategic value in Afghanistan,” he said. “It wants to prevent Uyghur rebels from finding sanctuary there and hopes to expand the CPEC to include Afghanistan. These moves show how quickly China has adapted to the new regional realities, where the US has retreated.”

The volatility of the South Asian region also underscores the volatility of the American political landscape. “India cannot afford to base its foreign policy on personalities or short-term alignments,” said Rappai.

Through Operation Sindoor, Modi has not just delivered a stern message to Pakistan, but blunted the risk of aligning too closely with America for the time being. Or, possibly, until political winds shift in Washington.