The India-Pakistan face-off lasted from May 7 to May 10. Expectedly, conflicting claims emerged of punishment inflicted by each side on the antagonist. Air-battles were fought, involving fighter-jets, drones and missiles. But, President Donald Trump’s claims of mediation have complicated matters.

Trump announced the ceasefire on May 10, before Pakistan or India went public. Normally such announcements are simultaneously made by the parties concerned. Karoline Leavitt, the White House spokesperson, listing Trump’s recent achievements included him having “secured ceasefire between India and Pakistan”. Trump in turn praised the “strong and unwaveringly powerful leadership” of both nations. After hyphenating India and Pakistan, which India resents, he promised substantially increased trade with both and sought a “solution concerning Kashmir”. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, in his statement, mentioned talks between the two combating nations on multiple issues “at a neutral location”.

The Indian government was embarrassed as the opposition demanded how third-party mediation arose. India has consistently sought bilateral dispute-resolution under the 1972 Simla Agreement. The US hinted at having threatened punitive tariffs if their ceasefire demand was ignored.

Arriving in Saudi Arabia on May 13 on a four-day Gulf tour, Trump again seized the India-Pakistan situation. Praising Rubio, he facetiously suggested the leaders of both nations having “a nice dinner together”. He added, to the audience’s amusement, that India and Pakistan should trade goods, not missiles. Significantly, in 2019 also, with Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan by his side at the White House, Trump related how two weeks earlier, at the G-20 summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi sought his mediation on Kashmir. Indian response came two weeks later with the abrogation of Article 370 and the altered status of Jammu and Kashmir.

However, ten years after President Trump’s last attempt at peacemaking in South Asia, the context is different. He has already destabilised the global trading regime with his misconceived faith in tariffs for rebalancing what he calls an anti-US global trading and economic order. An India-US trade agreement is still in the works. Hence the Indian reluctance to publicly contradict or challenge Trump on his frequent fact-free claims.

The world might be getting used to Trumpian tactics, as The New York Times noted. He is seen as adopting maximalist positions, unleashing chaos, and then backing down to finally declare a win. His aim is to reshape global trade and re-industrialise America. But the high tariffs are a double-edged sword that could harm the US economy in the short to medium terms. India wants to avoid confrontation.

Pakistan is naturally elated over the outcome of the five-day conflict. They see the Kashmir issue revived and re-internationalised. The US has arrived as a mediator, which India has always feared and rejected. Pakistan’s claims of shooting down Indian fighter jets, including one or more Rafales, are not being rejected internationally or by India in clear terms.

The Indian gains are mostly intangible, except the weaponisation of the river waters. Pakistan’s nuclear blackmail stands negated as Indian missiles targeted terrorism breeding and training centres across Pakistan. Finally, India has demonstrated its defensive and offensive capabilities in remote and aerial warfare. But the lack of demonstrable escalation dominance has left the Indian public opinion sullen, with even the hawkish pro-BJP elements bemoaning premature ceasefire.

Modi addressed the nation, but avoided facing the opposition or the media. He rejected dialogue on terms specified by Rubio, asserting that only terrorism and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir would be discussed. But he thus conceded that backchannel talks or diplomacy were not ruled out. He also explained the ceasefire as a pause, not a finality. And he brandished the river waters as the new weapon, for appropriate use. Unsurprisingly, within minutes of his speech ending, Pakistani drones intruded into Indian airspace in Punjab and Jammu & Kashmir. The Pakistani army appears willing to risk reigniting conflict to challenge the freshly fine-tuned Modi doctrine.

Also Read

- Mining for peace in Pakistan: Is US's interest in mineral wealth shaping the shift?

- Media, missiles and mistrust: Lt Gen D.S. Hooda (retd)

- Operation Sindoor was also a DRDO and Indian industry success story

- India’s new doctrine is based on sound homework

- BrahMos: An unparalleled weapon

- 'General Asim Munir could attempt a coup or bring Islamist parties to power': M.J. Akbar

Because Pakistan wants the US involved, it may keep tension ongoing by occasional but symbolic provocation. The newly pronounced Indian doctrine of treating any terror episode as an act of war is risk prone. Any individual jihadi can trigger an Indo-Pak war. The post-Balakot doctrine of rejecting dialogue till terrorism ends and sidelining Pakistan stands stymied.

In fact, to keep outside powers from intruding, the India-Pakistan dialogue needs revival. Of course, unlike the Composite Dialogue dating from 1997, it requires a fresh agenda. Meanwhile India must review and upgrade its military capabilities. China now supplies 81 per cent of Pakistani military equipment, which has clearly improved Pakistani capabilities. The river waters are now weaponised to counter Pakistan’s sponsorship of terrorism against India. Trump may lose interest in South Asia if tensions dissipate.

Operation Sindoor does not mark the beginning of the end of the India-Pakistan face-off. It is just the end of a new beginning.

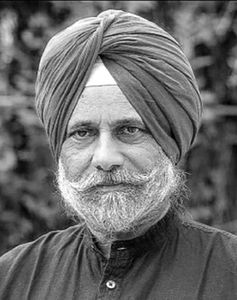

The author was ambassador to Iran and the UAE.