ANKUSH MAKES HIS living as a witness for couples who opt for a registered marriage in Mumbai. He first meets Deepa outside the Dadar marriage registration office, situated amidst a bustling market. The air is cacophonous with the call of paan wallas and coconut sellers with their rattling wheelbarrows. She is seemingly waiting for an absentee bridegroom. “Sister, looking for a witness?” he asks her. “Only Rs200. Standard charge.” She brushes him off, but as dusk seeps in and he sees that she has not left, he offers to help her find lodging for the night. Thus begins a friendship that soon blossoms into romance.

The story was one of the episodes titled Witness of Star Bestsellers—a show that aired on Star Plus in 1999-2000. Star Bestsellers presented a ‘mini-movie’ every week, directed by then-unknown filmmakers who are now some of the biggest names in Bollywood—like Imtiaz Ali, Anurag Kashyap and Anand Gandhi.

According to Ali, who directed Witness, those were exciting days to be working in television. “No one really knew what worked,” he says. “Everyone was trying to do different things as we were all ignorant of what the mechanism was that would ultimately strike gold.” Those days, he says, anyone could watch the shows. Later, to get advertisements, the channels started targeting specific audiences. “Subsequently, things became very regimented,” he says. “The corporate work structure came into television and it was no longer a land of dreamers. Directors were replaced by actors, writers and producers. It became a factory.”

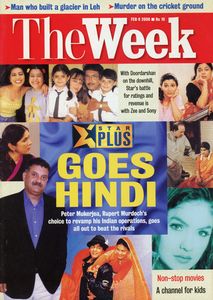

2000 was a landmark year for Star India. It was the year the channel decided to go ‘100 per cent Indian’. Those days, Zee and Sun TV were the only satellite channels making a profit, although others, too, were riding the wave of the mid-1990s satellite TV revolution. Over the previous two years, Zee had registered a growth of 31 per cent, Sony 179 per cent and Star 79 per cent. “Star has to go local and air more low-brow but mass-based entertainment programmes which appeal to north Indian taste, to really make a dent in Zee’s viewership,” THE WEEK quoted media consultant Sunil Y. Kalra in its cover story, Star Plus Goes Hindi (February 6, 2000).

2000 was also the year that Star came up with two things that would significantly change the complexion of Indian society—Kaun Banega Crorepati and the K-serials. “Across upmarket drawing-rooms and one-room joint families in suburban chawls, the young and the old alike are dialling those magical numbers starting with 9390…. At stake is big, easy money,” THE WEEK wrote. As political psychologist Ashis Nandy pointed out, the middle class had enough spare time, but not enough money, to fulfil what they wanted to do. Indians became obsessed with getting rich quick.

The year also spawned the K-serials—Kyun Ki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi (KKSBKBT), Kahaani Ghar Ghar Ki (KGGK) and Kasauti Zindagi Ka. The heroines of these shows epitomised ‘Indian values’ and, some speculate, was a reflection of the rising Hindu consciousness of the time. Saas-bahus became a dime a dozen as other channels, too, copied Star’s successful formula. For the first time, women were put at the centre of story-telling. “In the world before the Star TV of 2000-2010, many of the big changes happened through films. And films, largely, tended to be male-centric,” says Gaurav Banerjee, president (Hindi entertainment), Star India. “I think that changed [with the K-serials]. From KKSBKBT to Diya Aur Baati Hum, it was a massive shift in society…. It created a nation where gender issues got spoken about in households.”

Television moved from the K-serials of 2000 to reality shows like Bigg Boss and Indian Idol to socials like Balika Vadhu and Bandini to news as entertainment, when debates on news channels became scripted dramas. Today, says filmmaker and critic Dr Piyush Roy, all of them more or less co-exist on television. According to him, there are two prevalent societal trends that are reflected on television channels like Star. The first is the rise of the historical or mythological drama. “History is making a major comeback,” he says, “whether it is in people’s speeches or in entertainment.” There is a resurgence of jingoistic content glorifying India, in which we reclaim our identity and who we were.

There is also the rise of the personality cult, where the protagonist overshadows the others, whether it were the shows on Chandragupta Maurya or Chanakya. Although many historicals have come back on television, the last game-changer, according to him, was Siddharth Kumar Tewari’s Mahabharat, which played on Star Plus from 2013 to 2014. “There were a few other Mahabharats and Ramayans playing on television in the 1980s but they were made without technical expertise or vision,” says Roy. “Tewari’s Mahabharat became so popular that all the Pandavas became famous in places like Indonesia. The person who played Arjuna was like the Shah Rukh Khan of Indonesia. That was followed by too many costume dramas on television which were made without proper research and written like extended saas-bahu shows.”

The second trend, according to him, is the rise of self-help. “If you want to know what is trending, just go to an airport bookshop,” says Roy. “Today, you’ll see primarily two genres—books re-interpreting history, like those of Amish and Devdutt Pattanaik, and self-help. The more urban and lonely we are, the more we look for knowledge and inspiration from different avenues.” Star was perhaps the first to capitalise on this with its TED Talks in 2017. “We are trying to make a niche idea like TED Talks cool,” says Star’s Banerjee. “One thinks they are only given by Nobel winners and intellectuals. We want to make it accessible… [so that] everyone in the country can watch and engage with it.”

Star India has come a long way in 20 years, becoming the reigning Hindi general entertainment channel not long after the 2000 revamp. Only in 2009 was Star Plus overtaken by Colors, Viacom18’s flagship entertainment brand, for a brief period. From Rs365 crore in 2000, Star India’s revenue has jumped to Rs12,341 crore in 2019. It broadcasts 60+ TV channels in eight languages in India, reaching more than 790 million viewers every month. It has been the torch-bearer of change in many ways, whether it was by inspiring aspirations of wealth in millions of Indians through Kaun Banega Crorepati, bringing social issues to the limelight through Satyamev Jayate or looking at mythology from a woman’s point of view through Siya Ke Ram.

Just like in 2000, when THE WEEK wrote that Star was “the most exciting place to be in right now”, today, too, Star is at the helm of exciting innovation with its streaming platform, Hotstar, which boasts over 300 million users, compared with just 5.2 lakh subscribers for Netflix in India. “Technology and creativity are converging in a very important way [today],” says Banerjee. “We are thinking about how analytics can help us tell better stories. What is the role that CGI plays? How can sets be made and lighting be done [differently]?” In 20 years, from Star going Hindi to Star going digital, the medium and mode of story-telling might have mutated, but the stories themselves remain. When we lose our stories, we lose our soul, and if anyone knows that, it is Star.

—With Priyanka Bhadani

STAR INDIA'S REVENUE

2000 - Rs365 crore

2019 - Rs12,341crore