RISHABH PANT WAS a toddler in Roorkee when M.S.K. Prasad, India’s wicket-keeper, walked out to bat in Adelaide in the 1999-2000 Test series. Nearly 20 years later, Pant walked to the middle in Adelaide as India’s wicket-keeper; as the chief of the selection committee, Prasad had green-lighted Pant’s entry into the team.

Back in 2000, in THE WEEK’s cover story ‘Sitting ducks for the Kangaroos’, former Australian batsman Dean Jones had said, “M.S.K. Prasad has the goods. The wicket-keeping problem will eradicate itself if he is given longer time and confidence.”

Unfortunately for Prasad, his career petered out soon enough. But, perhaps, as selector, this made him want to persist with a keeper for longer, and Pant was given many a chance after the Australia series. He is, however, yet to cement his place in the side.

If India was playing musical chairs with its wicket-keepers then—Nayan Mongia was nearing the end of his career and the next one or two years saw a slew of keepers, including Vijay Dahiya, Saba Karim, M.S.K. Prasad and Sameer Dighe—it seems to be in no better a position now. In a post-M.S. Dhoni era, the likes of Wriddhiman Saha, Pant and Sanju Samson are vying for a permanent place in the team.

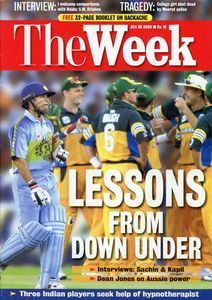

The keeping quandary, however, was perhaps the only arguable similarity between the Indian teams of 2000 and 2019. In its cover story, THE WEEK had summed up the 1999-2000 series thus: “It may sound cruel. Even unpatriotic. Some folks feel that comparing the Indian team with their Australian counterparts is likening a company with an ISO 9001 rating to one that is controlled by feuding partners. One has men vying with each other for excellence, the other is choc-a-bloc with non-performing assets.”

Two decades later, Sachin Tendulkar, the captain in the 2000 series, told THE WEEK: “I think our performance [in 2018-19] has been really good. The bowling has been terrific. It has been a complete performance [by the Indians].”

If the team had lost 0-3 in 2000, it won 2-1 in its latest tour (its first Test series victory in Australia). It also showed improvements across disciplines, particularly bowling.

Let us take it one at a time. First, batting. Tendulkar scored 278 runs in three Tests. V.V.S. Laxman made 221, but apart from a 167, he was largely inconsistent. The usually dependable Rahul Dravid made just 93.

Compare this with Cheteshwar Pujara, who scored 521 in four matches, including three centuries. “While I was batting, [Australian spinner] Nathan Lyon came up to me and said: ‘Don’t you get bored?’ It was funny,” Pujara told THE WEEK. “They saw my face for most of the series and got bored seeing me bat. I had toured to Australia earlier in 2015. I knew the conditions well. When I was in India, I had a couple of weeks of training on pitches that had pace and bounce. My preparation was up to the mark.”

As for the 2000 series, he said, “I had watched it on television. We played really well. We had great batting lineup and some good bowlers, but our fast bowlers are much better now. And there is healthy competition in the team.”

Apart from Pujara, the thorn in Australia’s side, there was Virat Kohli who made 282, Ajinkya Rahane with 217, Pant with 350 and a debuting Mayank Agarwal who made 195 in two matches.

Also, Australia had declared thrice in that series, but not once in the latest one. India declared thrice in the latest series, but zero times in 2000.

“The Indian side I played against in 2000 seemed to be more worried about the fast, bouncy wickets than on their game plans,” Australian bowling legend Glenn McGrath told THE WEEK. “[The Indian batsmen now have] a more positive mindset and the pitches in Australia are not as quick and bouncy as they used to be. They have had plenty of experience playing on the pitches in Australia and South Africa. Also, the different mindset may be because of tournaments like the Indian Premier League. Indian players are exposed to international players more, they see how they prepare, play and go about things, [and] they realise they are normal cricketers like everyone else.”

Coming to the bowlers, Javagal Srinath took 10 wickets in the three matches, Venkatesh Prasad took seven, Ajit Agarkar got 11 and Anil Kumble scalped five. In the last series, Jasprit Bumrah got 21 wickets in four matches, Mohammad Shami took 16 and Ishant Sharma took 11 in three matches. India bowled out Australia in all seven innings (one was washed out). The team had bowled out the Aussies only twice in the 1999-2000 series.

Another important difference was the short ball. The Indian batsmen were known to be vulnerable against the bounce and pace of Australian pitches, but they showed more tenacity last year. The bowlers, especially, took a liking to short balls and India gave as good as it got.

“They are a quality bowling attack,” said McGrath. “They have pace, skill, experience and variety. Shami is a class bowler who can get the ball through at good pace, move the ball in the air and off the seam. Combine this with experience and guile, and he is a proven wicket taker. Bhuvneshwar Kumar can swing the ball. Umesh Yadav has serious pace. Ishant, experience. Bumrah has been a revelation, bowling at serious pace of such a short run up, moving the ball in the air and off the wicket and bowling great areas. [It is] a world-class bowling attack with the ability to take 20 wickets on a regular basis.”

In THE WEEK’s 2000 story, former Australian batsman Dean Jones had observed that, “The Indian team still lacks a sense of camaraderie and the attitude to play for each other.” While this may or may not have been true, it certainly would not apply to the current team. Especially the bowlers, who worked as a team to prey on opposition batsmen. Just watch the video of commentator Harsha Bhogle interviewing Ishant, Shami and Umesh Yadav after the recent win against Bangladesh. Amid quality banter, there were nuggets of information about their plans to work as a unit.

“I think it is about the number of players who are available,” said Pujara. “In bowling we have replacements in case of injuries. The reason is domestic cricket and IPL. Most of the fast bowlers have come from the IPL. I hope it continues.”

As for fielding, Jones had this to say about the 2000 team: “Many players struggle to throw over 60 metres and their athleticism and agility are also being tested.” Contrast this with the current Indian team, which has a handful of the best fielders in the world, and Ravindra Jadeja, in particular, who throws bullets from the outfield.

Also in focus then was Tendulkar’s captaincy, and how it seemed to have burdened him. Though he denied any pressure because of the post, the results were telling: India won only four of 25 Tests under him. Many felt he took on too much and the others, too, looked to him for everything.

But if captaincy impeded Tendulkar, it seemed to have spurred Kohli. He is currently the most successful Indian captain in Tests, with 33 wins in 53 matches. His team, too, looked more confident. The drooping shoulders of yesteryear were replaced by confident bodies; sledging was no longer a one-way street, and every “babysitter” jibe had a “temporary captain” retort.

“It varies from person to person,” said Pujara. “But, as a team, if we feel that we need to sledge them, we definitely will.”

Said McGrath: “I like Virat’s attitude and aggression. He gives confidence to the other players to back themselves against the opposition.”

As for the infrastructure and training aspects, THE WEEK, in its story in 2000, had said that, “Development of junior cricket [is important]. The idea of starting the National Cricket Academy should be pursued to its logical end.” Something on the lines of the Australian Cricket Academy would be good for young Indian players, Tendulkar had then said. The National Cricket Academy was established in Bengaluru the same year, and has since honed many an international cricketer for India.

THE WEEK’s story then had also noted that, “Slick marketing has popularised the game in Australia. The ACB has spent millions to make the game more enjoyable... [it] earned a profit of $(A)3.5 million for the current financial year. Its website is the fourth most popular in Australia. The Indian cricket board does not even have an email ID!”

Nearly two decades on, the BCCI, now led by Ganguly, has become a behemoth, controlling not only Indian cricket, but also a major part of the global sport. It is by far the most influential board in the world, and that has obviously had an impact on its team.

Spin legend Anil Kumble, in an article for Livemint in 2013, had highlighted four paradigm shifts, starting from the early 2000s, that changed the Indian team. The first was a non-Indian think tank. Foreign coaches and support staff were introduced and reluctantly welcomed by pundits. But New Zealander John Wright put to rest any reservations people might have had. There was also a realisation that a team was not just players and a coach, and physiotherapists and other specialists were brought on board.

The second shift Kumble mentioned was the famous huddle. He argued, from experience, that the huddle encouraged players, especially youngsters, to shed their inhibitions and voice their opinions. “Fielding is when the team is usually disconnected, unless a wicket falls,” he wrote. “We used wicket breaks, drinks breaks, start of a game and other impulsive opportunities to initiate the huddle. People started voicing their thoughts, appreciating one another, sharing information and [went] back charged.”

The third shift was about expanding the ‘planning’ bit beyond senior players and creating multiple captains for batting, bowling and fielding. And, the fourth was the introduction of format-specific captains and the maturity that was shown when a young captain (Kumble specifically mentions Dhoni) takes over a senior team.

Overall, the past 20 years have produced a sea change in Indian cricket. The flashes of individual brilliance have been replaced by a well-oiled machine and the team is no longer an underdog. Nor is it mercurial like its northwestern neighbour, which some may argue makes for more exciting cricket.

Regardless, consistency has become India’s hallmark. And though winning Tests in some countries is still a stiff ask, that is true of all teams today. Overall, India has cemented its place as one of the best.

If only the position behind the stumps was also set in concrete.

—With inputs from Nandini Oza

HIGHEST SCORER (1999-2000 AND 2018-19)*

Sachin Tendulkar 278; Cheteshwar Pujara 521

HIGHEST WICKET-TAKER*

Ajit Agarkar 11; Jasprit Bumrah 21

* Three Tests in 1999-2000; four in 2018-19