The more things change, the more they remain the same. Or do they, really?

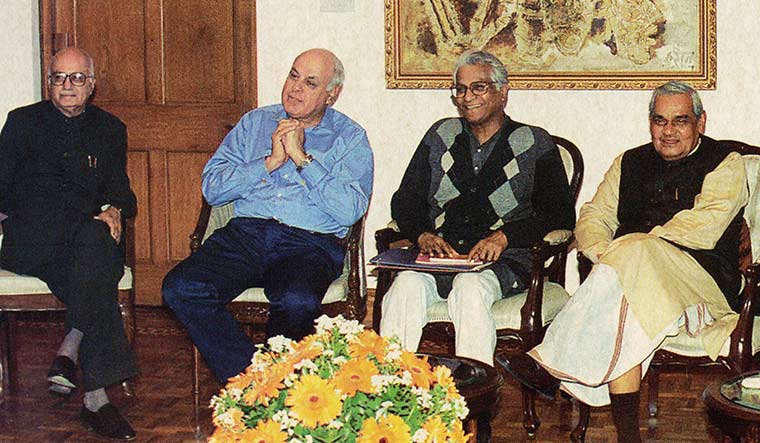

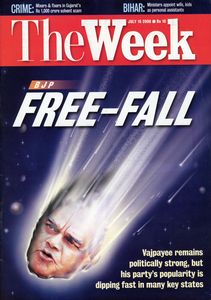

In July 2000, THE WEEK reported on how Atal Bihari Vajpayee and the BJP were moving in opposite directions in the popularity stakes. The prime minister’s stock was soaring, but his party was wracked by rebellions in several key states—that, too, barely a year after the Lok Sabha polls, which the BJP-led alliance had won decisively. Regional headaches were plaguing the party, though it remained strong nationally, thanks in part to the Congress, “which, beset with internal problems and inexperienced leadership, has proved a mild and manageable opposition”, wrote THE WEEK’s correspondent Debashish Mukherji.

Two decades on, the story seems the same—a popular prime minister in Narendra Modi, a strong but increasingly unlikeable party led by Amit Shah, and regional headaches. All this, barely a year after the Lok Sabha elections, which the party had won on its own. “The BJP’s aggression to expand its reach has put off some of its allies, as many of them want more space,” wrote THE WEEK’s special correspondent Pratul Sharma, a day before the BJP’s oldest ally, the Shiv Sena, joined hands with the Nationalist Congress Party and the Congress to form government in Maharashtra. “At the national level, though, the Modi-Shah duo remains untouched.”

The BJP’s troubles then and now may appear similar; but they are vastly different in nature. Ajay Gudavarthy, who teaches political studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University and has authored India After Modi: Populism and the Right, defines this disparity in terms of the BJP’s acceptability. “Vajpayee belonged to an era when the consent for hindutva politics was very limited,” he told THE WEEK. “He understood the times very well. So he projected himself as the BJP’s Nehruvian face—as someone who was more accommodative—because he knew that popular consent was for the Congress style of politics.”

But Vajpayee could still reveal himself as a rigid right-winger when he chose to. An example is his unusually forceful speech in Lucknow on December 5, 1992—the day before the Babri Masjid demolition. “The Supreme Court has asked us not to start any construction work [at Ayodhya],” he told kar sevaks gathered at Aminabad for their journey to the disputed site. “But the court has told us that you [can] conduct bhajan and kirtan there. And bhajan is not done by one person; it is done together with others. We need even more people for kirtan. And bhajan and kirtan cannot be done while standing…. There are sharp stones there; so we cannot sit on the ground. The ground will have to be levelled.”

The masjid was demolished the following day.

But Vajpayee was shrewd enough to know that what worked in Lucknow could not have worked in Delhi. So, in the eight years post Lucknow, he fashioned himself as the urbane face of the BJP. Virulent speeches were out; gentle poetry was in. (Some of the poems were not really gentle, though. “Hindu tan man, Hindu jeevan, rag rag Hindu mera parichay,” read one. I am a Hindu—body, mind and soul; every speck of me is Hindu. The line was so stirring and stern that RSS chief K.S. Sudarshan told men in shakhas to chant it every morning.)

The Nehruvian image of Vajpayee was largely a product of the circumstances. He was a strong prime minister not because of his party’s position in the Lok Sabha, but because of the support he had from his coalition partners. Vajpayee was also the perfect foil for the fiery L.K. Advani, who wielded more influence in the BJP. But this also made him dependent on the coalition. So much so that he had to grin and bear it when Farooq Abdullah of the National Conference passed an autonomy resolution in the Jammu and Kashmir assembly in June 2000—a move that virtually cocked a snook at the BJP agenda to assimilate Kashmir into India.

Vajpayee, however, was not as accommodative of Modi as he was of Abdullah. When Modi, as Gujarat chief minister, failed to control the riots that broke out in the state in 2002, the fear of losing his hold on the party and the government moved Vajpayee into action. “He pulled a piece of paper and started writing his resignation,” recalled former Union minister Jaswant Singh in 2009. Parliament was in session then, and Singh was asked to pacify a “disturbed” Vajpayee, who had shut himself in his parliamentary office.

“I held his hand and he looked at me severely and I said, ‘What are you doing? Don’t do this.’ I somehow persuaded him,” said Jaswant. “We went to his house, and we were able to defuse the situation.”

But the hindutva fuse was lit, and Vajpayee must have known it. When the BJP’s national executive met in Goa later that year, Modi staged a coup. He reportedly told the leaders that he was ready to step down over the riots, but many asked him to reconsider. “Vajpayee kept mum, opting against a confrontational stance,” wrote journalist Ullekh N.P. in The Untold Vajpayee: Politician and Paradox. “Perhaps, for all his bravery, he was worried about younger leaders publicly questioning his authority.”

Two years later, Vajpayee lost the Lok Sabha polls. He faded from politics and made his last public appearance in 2007, the year Modi won his second full term as chief minister. “If you look at what you see today, 2002 was really the watershed year,” said Gudavarthy. “Had Vajpayee stood firm, and had there been major condemnation of the riots, Modi would have fallen by the wayside and history would have forgotten him. But that did not happen. That is the gamble he took, and it paid off.”

In a way, it was not a gamble at all. A year after the riots, Modi had organised the first Vibrant Gujarat summit, which had investors from around the world pledging thousands of crores to start businesses and generate jobs. By 2007, Modi had succeeded in minting a new kind of political currency—the heads of the coin was development; the tails was hindutva.

After Modi’s 2007 victory, scholar Ashis Nandy succinctly captured what had happened in Gujarat. “The middle class is at the moment having a love affair with hatred and paranoia,” he wrote. “Like Bengali babus and Kashmiri Muslims, Gujaratis were traditionally classified as non-martial by the British Empire and they smarted under that classification. Even when they themselves do not embrace violence, they vicariously enjoy it. They enjoy it even when the violence is directed towards them. In Surat, there is now a statue of Shivaji, who sacked Surat more than once! Modi has tapped into that self-hatred of the Gujarati middle class, and the sanction for violence that flows from it.”

***

A clinical psychologist, Nandy had interviewed Modi in 1992, to understand how the mind of a radical worked. Modi was then just an earnest RSS pracharak who had just been deputed to the BJP. Nandy wrote about the interview ten years later, after Modi became Gujarat chief minister. “The long, rambling interview,” he wrote, “left me in no doubt that here was a classic clinical case of a fascist.”

In 2007, Nandy modified his opinion. He found that Modi had “retooled himself as a typical, middle-class politician” because he had “larger, pan-Indian ambitions”. “Modi’s earnestness, thankfully, has declined; he has become more instrumental. He is at once less threatening and more dangerous. He can now go farther in politics with his personality and psychological resources,” he wrote.

In 2012, when Modi began preparing for Delhi, Nandy came out with an advice: “My dear friend, if you wish to play a larger role in national politics, you need to reflect. You cannot go directly from the chief minister’s office in Gujarat to the prime minister’s office in New Delhi. Buy peace in the interregnum. You should go to a dargah. Go to Ajmer Sharif and apologise. The Khwaja is supposed to be benevolent and very forgiving.”

Modi took the advice, but on his own terms: He sent a chadar to the dargah the year after he became prime minister.

“Everyone assessed Modi wrong,” Nandy told THE WEEK. “They all underestimated him. But he ultimately proved to be clever.”

In 2014, the BJP became only the second party in India ever to win majority on its own in the Lok Sabha. Under Modi, the party was largely freed from the burdens of coalition politics. Congress-style politicking was done; time was ripe for Congress-mukt Bharat. If Vajpayee latched on to his Nehruvian image, Modi made no secret of his loathing for Nehru.

But the clearest sign that the Vajpayee era had truly ended came on August 5 this year, when the Union government took away Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy and reorganised it as two Union territories. Farooq Abdullah, who had felt secure enough under Vajpayee to pass an autonomy resolution, has been in jail since then.

NCP president Sharad Pawar recently weighed in on what set the two BJP prime ministers apart. “Vajpayee saheb, while taking any step, would usually take care that there was no bitterness,” he said. “Modi has the ability to implement a decision ruthlessly once it is taken.”

It is obvious that Modi sees politics as a zero-sum game, in which the BJP stands to gain from whatever losses the other parties suffer. This has mostly worked in the past six years, and it has helped many a saffron dream come true. But, by weaning the Shiv Sena off from the BJP’s deadly embrace, Pawar has exposed a major flaw in Modi’s gameplan.

“But the BJP has not been weakened, despite Maharashtra,” Nandy told THE WEEK. “That is the only place where they have seen a real defeat. It is slightly worrying for them because Bombay happens to be a very productive source of finances. What I notice is this: There is some discomfort within the BJP, and some self-doubts, too.”

A real cause of worry is that the hindutva bandwagon has hit its first major roadblock. Violent protests have erupted in Assam, where the BJP wants to grant citizenship to Hindu refugees from Bangladesh. According to Nandy, the BJP is out of its depth in the northeastern state.

“The BJP did not anticipate these protests at all,” said Nandy. “They thought the moment they allowed the [Bengali] Hindus to be kept out of [the National Register of Citizens], everything will be hunky-dory. That it will keep the Assamese satisfied. The BJP thought that, after the NRC, the Assamese will have some sympathy [for Bengali Hindus].”

The BJP’s big mistake was in assuming that religion would ultimately trump ethnicity. “To those who know Assam, it was obvious that the Assamese were primarily against Bengali Hindus, who had come from Pakistan mostly, and their dominance in various walks of life,” said Nandy. “Everything said, the Muslims may be tilling land in Assam, but they are politically not that important. Their voice is not heard that much. Whereas Bengali Hindus are dominating Assam in various ways, even from colonial times.”

But states like Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha also have sizeable Bengali populations, so why is an Assam-like resistance not happening there? “In Bihar and Jharkhand, this has been shrouded by the fact that political power is primarily in the hands of Biharis. This is the case in Odisha as well. But in Assam, the Bengalis have now become so sizeable that the Assamese are feeling marginalised.”

The ethnicity factor in the resistance against hindutva is most apparent in Tamil Nadu. #GoBackModi trends on Twitter whenever Modi visits the state, and his best efforts to woo the Tamils—he wore a white mundu and a half-sleeved shirt to an India-China summit—have all gone in vain. Even in neighbouring Kerala, Modi’s moves elicit more sniggers than admiration.

Vajpayee tried to skirt around these regional fissures by deploying leaders like Rangarajan Kumaramangalam. A Congress trouble-shooter on Ayodhya in the early 1990s, Kumaramangalam joined the BJP in 1997. A mass leader in his own right, he became one of Vajpayee’s most trusted lieutenants in Delhi and the party’s standard-bearer in Chennai.

Under Modi, though, the BJP leadership has become more homogenous. “Basically, you are dealing with a leadership that is narrowly Gujarati,” said Nandy. “They have no experience in connecting to a pan-Indian world. A little bit to Maharashtra or Bombay; that’s about all.”

Modi also cannot hold a candle to Vajpayee in politicking. Soon after THE WEEK published its cover story in 2000, Vajpayee increased his grip on the party with a string of swift moves. He got Bangaru Laxman unanimously elected as BJP president in August, and then got Laxman to change the composition of the team of office-bearers the next month.

It was not a complete overhaul, but a carefully managed shake-up that helped Vajpayee bring in new leaders and keep the Advani camp in check. Sushma Swaraj was excluded from the party’s national executive, but Modi was retained as a general secretary; Madan Lal Khurana, viewed as a dissident by the Advani camp, was made vice president; K.N. Govindacharya, the rising ideologue who had earned Vajpayee’s wrath, ceased to be general secretary. (Govindacharya was rather unlucky: In an interview, he had described Vajpayee as the “face” of the BJP. An RSS journal translated the word not as chehra, as it should have been, but as mukhota, which meant mask. He never recovered from the fall.)

If Vajpayee was never bigger than his party, Modi projects himself as the party. The only leader he has let out of his shadow is his longtime second-in-command, Union Home Minister Amit Shah. Their relationship has so far been synergetic and symbiotic—the reason why Modi let Shah take the limelight when the BJP finally implemented its long-cherished Kashmir plan.

“There is no second-rung leadership in the BJP,” said Gudavarthy. “Now, every leader other than Modi and Shah looks like a caricature. They make irritating statements, and appear ridiculous. This is a crisis that is going to hit the BJP at some point.”

There is, however, a bigger and far more urgent crisis that may end up consuming the party and the government. The economy is teetering, and the BJP does not have enough able hands on deck to keep it in control. The political currency that Modi had minted in Ahmedabad is fast losing its sheen in Delhi.

“Many things Modi has done, the people have been kind enough to forget, thinking that he will do good things for them,” said Nandy. “But now they have seen that even those things have not worked out. The honest economic estimate is that one crore people lost their jobs because of demonetisation. Now everybody is worried about jobs, particularly in Assam…. The people had not bargained for this part of the deal.”