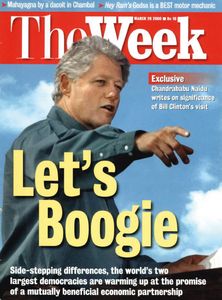

ON MARCH 22, 2000, an unusual spectacle unfolded in Parliament’s Central Hall, which had witnessed several solemn occasions, including Jawaharlal Nehru’s “tryst with destiny” speech. Visiting US president Bill Clinton had just finished his address to the joint session of Parliament and was proceeding towards the exit. Suddenly there was a commotion, with MPs “jumping on chairs and over benches to shake Clinton’s hand”. The New York Times reported the next day that India was afflicted by the famous “Clinton fever”.

The tables were turned, two decades later. On September 22, 2019, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed a gathering of 50,000 Indian Americans in Houston, President Donald Trump flew down from Washington to give him company. The governor of Texas and the state’s congressional delegation were on stage to greet Modi in what was the largest-ever gathering for a foreign political leader in the United States other than the pope. They listened to Modi’s hour-long speech and his enthusiastic endorsement of Trump’s second term. “At rally for India’s Modi, Trump plays second fiddle,” wrote The New York Times. From wary acquaintances to priority partners, India and the US have come a long way in the past two decades.

From an Indian perspective, the single most important change has been the shift from reflexive anti-Americanism to a more accommodative stance, says Uma Purushothaman, who teaches international relations at the Central University of Kerala. The Indian strategic thinking freed itself from the rigid boundaries of the Cold War, when the default position was almost always in favour of the Soviet Union. Ironically, the nuclear tests conducted by the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government in 1998 triggered a new line of thinking about India in the United States, too. Although the tests resulted in stringent anti-India sanctions, it also led to extensive engagement between the two countries, most notably the eight rounds of talks between deputy secretary of state Strobe Talbott and foreign minister Jaswant Singh. The US also took into account India’s growing economic potential unleashed by the financial reforms initiated by the P.V. Narasimha Rao government. This was the springboard from which India-US relations took a giant leap.

“There has been a cognitive shift in how the leadership in each country perceive the other country, and the shift has been—for the most part—unusually bipartisan,” says Mahesh Shankar, director of the international affairs programme at Skidmore College, New York. “In India, the shift has been from viewing the US as an imposing and almost imperialistic superpower to recognising it as an economic and strategic partner. In the US, it has involved moving from viewing India as something of a nuisance actor in a nuisance region to accepting it as a legitimate ideological and strategic partner and an emerging great power.”

The US recognition of India’s strategic significance got reinforced after the 9/11 attacks, which led to president George W. Bush launching his “war on terror”. The deadliest terrorist attacks ever on American territory and the challenge posed by radical Islam convinced the US that India’s concerns regarding terrorism were true. It influenced Bush’s decision to elevate India as a key strategic partner and sign the civil nuclear deal—a groundbreaking move as India has steadfastly stayed out of all global non-proliferation regimes. The deal was so one-sided and unprecedented that in Washington it was referred to as a “gift horse”.

The first two decades of the 21st century also saw the US decoupling Pakistan from its ties with India. “All these, of course, have been driven from the American point of view by India’s economic growth and the possibility of India as a counter to manage China’s rise,” says Purushothaman. Agrees Shankar, “China has been the one factor that has driven the strategic convergence between the two sides. This does not mean that there have not been challenges, like the Obama administration briefly floating the US-China G2. But for the most part, China’s rise has driven the strategic convergence between the two sides.”

One of the key manifestations of that strategic convergence can be seen in the defence sector. India and the US signed their first “foundational” military agreement called the General Security of Military Information Agreement in 2002, jumpstarting an era of enhanced defence cooperation. The Narendra Modi government signed the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement in 2016, which permits both militaries to use each other’s facilities for refuelling and replenishing. The Communications, Compatibility and Security Agreement, signed in 2018, allows the sale and exchange of encrypted data and equipment. The final foundational agreement, called the Basic Exchange Cooperation Agreement, is being negotiated now. Both countries have institutionalised a ‘2+2’ defence and foreign ministers’ dialogue. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has granted India Strategic Trade Authorisation Tier 1 (STA-1) status, which is expected to bring down export restrictions on high-tech defence and aerospace exports.

American defence sales to India have grown from $220 million in the early 2000s to $18 billion in 2019. By 2014, India had become the second largest buyer of US arms, with a share of over 11 per cent of American arms sales. Defence purchases include C-17 and C-130J transport aircraft, P-8I maritime reconnaissance aircraft, AH-64 Apache attack helicopters and Harpoon missiles. Both countries are in the advanced stages of negotiation for the sale of 24 MH-60 Seahawk multi-role naval helicopters. The deal could be sealed during the latest round of the ‘2+2’ meeting to be held in Washington on December 18.

“As we start to operationalise the concept of Indo-Pacific and restart the quad comprising India, the US, Japan and Australia, the US sees India as a bilateral partner which can constrain China and limit its influence in the region. I expect India-US cooperation in the defence arena to deepen further,” says Stuti Banerjee, research fellow at the Indian Council of World Affairs, Delhi. In May 2018, the US defence department renamed its Pacific Command as Indo-Pacific Command in a symbolic gesture to recognise India’s growing prominence.

“India already conducts more joint military exercises and defence dialogues with the US than with any other country,” says Joshy M. Paul, who is with the Centre for Air Power Studies, Delhi. In November, the two countries conducted their first-ever joint tri-services exercise called Tiger Triumph in Visakhapatnam and Kakinada. However, American reluctance regarding technology transfer and co-production of defence equipment is hampering further growth in ties.

“Somehow, the level of trust is not equal to what we enjoy with the Russians, probably because the US still remains reluctant to share high-end technology,” says Purushothaman. India, for instance, chose to go ahead with the purchase of S-400 missile defence system from Russia—a deal worth Rs40,000 crore—despite serious American objections including the threat of sanctions under CAATSA (Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act) and an offer to consider alternatives such as the Patriot and THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) systems. And, despite the spurt in defence ties with the US, India still imports over four times more arms from Russia.

While defence ties have grown, trade ties have fallen short of expectations. From $19 billion in 2000, India-US trade grew to $142.6 billion in 2018. But, to put things in perspective, US-China trade is worth $650 billion a year. The US is India’s second largest export market and third largest import market. The trade balance, which favours India, however, has become an issue of friction under Trump. India has taken strong exception to the US decision to impose 25 per cent tariff on steel and 10 per cent tariff on aluminium under section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act, which allows the president to restrict imports citing national security concerns.

In June this year, the US government terminated preferential tariffs to Indian exports under the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP). India was the biggest beneficiary of the programme last year, covering exports worth $6.3 billion. India responded by imposing higher tariffs on US exports, affecting products worth $1.4 billion.

India and the US have been unable to find a common ground on vexing issues such as balancing the intellectual property rights regime. The US feels that Indian laws are lax, while India believes it is only promoting innovation and keeping prices of essential items like drugs affordable. The US is also opposed to Indian demands on in-country data storage, especially for financial giants like Visa and Mastercard and social media platforms. “Trade has been a major letdown,” says Purushothaman. “The US seems to be unsympathetic to India’s development imperatives and priorities. If the US wants a strong India to counter China, it needs to give some concession to India so that it can develop its economy. It should not treat India like it treats China. Just look at the size of their economies!”

The high profile Indian diaspora in the US is yet another key variable that shapes the contours of India-US relations. There are around 46 lakh people of Indian origin in the US, up from 4.5 lakh in 1990. Nearly three times more Indian Americans have college degrees compared with the national average. With a median household income of $1,07,000, they have the single highest income level of any group, which is twice as high as the national average. The past two decades have seen a number of Indian Americans rising to political prominence, including former Louisiana governor and 2016 Republican presidential candidate Bobby Jindal, former US ambassador to the UN and governor of South Carolina Nikki Haley, California senator Kamala Harris who just dropped out of the Democratic presidential primary race and Congressmen Ami Bera, Ro Khanna and Raja Krishnamoorthi and Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal. India also sends a large number of students to the US every year, adding to the dynamic nature of the diaspora. In 2018, the number of Indian students in the US was 2,02,014, up three per cent from the previous year. Although they make up only one per cent of total American population, the Indian Americans, with their wealth, education, professional achievements and political savvy have had a key role in promoting India-US relations.

While no one doubts the significance of India-US relations and the potential for further growth, the historical baggage of mutual distrust, bureaucratic inertia and, of late, the unpredictability of the Trump administration, could hurt bilateral ties. “The US has the history of being a selfish partner as it cares only for its own interests,” says Paul. “So long as our interests align with theirs, the relationship will be smooth. But when it differs, we may find the situation to be uncomfortable. India should be particularly wary about the situation in Afghanistan and also its ties with Iran and Russia in this regard.”

A range of other irritants such as Kashmir, religious freedom, economic slowdown, outsourcing, immigration and H-1 visas could hurt ties. “In the long term, bilateral consensus in the US has moved enough that many of these issues are likely to move off the agenda once Trump leaves,” says Shankar. “Of course that could mean five more years, and those five years might reorient American domestic politics so much that the Trumpian perspective becomes the norm on one side of the political divide, thereby breaking what has till now been a bipartisan consensus regarding India.” And, that is the danger India should prepare itself to deal with.

INDIA-US TRADE

2000 - $19 billion

2018 - $142.6 billion