Sameera Nayeem used to hate her husband.

Nayeem is a college lecturer in Madhya Pradesh’s Dewas district, and her spouse, Mohammed Zakir, was an IT professional from Rajasthan. His big dream was to go the US, and it crumbled when 9/11 happened. He fell into depression, quit his job and went back to his village in Rajasthan to become a farmer. He came to lead a farmer agitation instead, demanding better water supply for his village. In the five years that Zakir led that agitation, several cases were slapped against him and his marriage almost broke down.

“I blamed my husband for all this,” Nayeem later wrote about the experience. “I also [blamed] my parents for marrying me to a person who loved society more than family.”

In the end, it was the Madhya Pradesh government that saved their marriage.

In August 2016, it set up a happiness department (Rajya Anand Sansthan), the first such initiative in India to evaluate the happiness quotient of citizens and to ensure the mental well-being of people. The department began holding joy-spreading workshops called Alpviram (pit stop) across the state, one of which Nayeem happened to attend.

“It opened my eyes,” Nayeem wrote in her testimony after the workshop. “After reaching home, I apologised to my mother and my father and confessed my mistakes to Zakir. Now we love each other.”

Also read

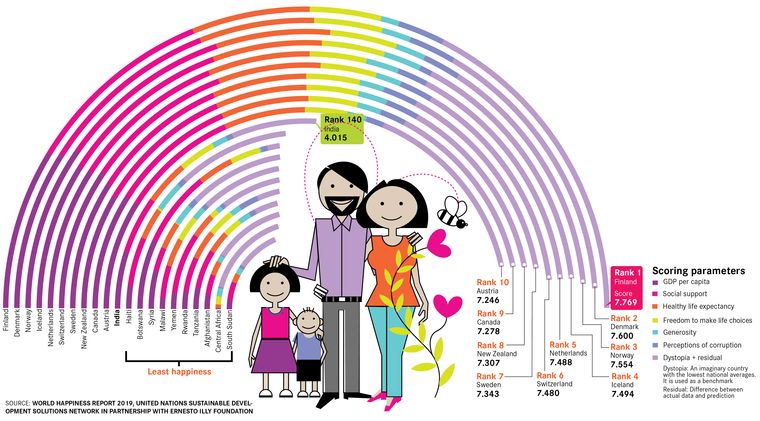

- Indices: Where India stands in global rankings

- India's demography: All's not well

- Climate change performance index: India rank 11

- Poverty index: India rank 49

- Health care: India needs more doctors

- India needs to spend more to educate its people

- Human rights a messy issue in India

- Liveability index: No Indian city in top 100

The website of Rajya Anand Sansthan features several testimonies similar to Nayeem’s. All of them say the government helped them find joy and become better individuals. Apparently, the department now has more than 30,000 people registered as anandaks (agents of happiness) who help organise village-level pleasure camps across the state.

Sadly, though, this isn’t a happily-ever-after story.

In the past 50 years, Madhya Pradesh has consistently been among India’s most under-performing states in terms of education, health and economic indicators. The Union government’s 1960 report on district-level industrial development found that 123 districts in Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh were so backward that they were dragging down India’s overall development. A similar report in 1996 said Madhya Pradesh had the second highest share of poorest performing districts in the country.

Of course, the state has made significant progress in the past 15 years. Human development indicators have shown improvement, and Bhopal is now the 10th most liveable city in India, according to the Union government. Also, the state’s happiness initiative has inspired governments in Maharashtra and West Bengal.

But, Madhya Pradesh and the three other states that set dubious records in the 1960 report are still considered India’s bimaru region. The question is, can citizens find happiness amid the governance sickness?

Perhaps, they can. And, surely, it is a good move for governments to finally focus on the happiness of their citizens. But then, you cannot commute to work through crowded, potholed streets with a wide grin on your face.