Inalienable. That is what human rights are supposed to be. Many in Assam, though, would disagree. On August 31, the state will publish the final draft of its National Register of Citizens, which might make 40 lakh residents, mostly Bengali-speaking Muslims, aliens in their own home.

The objective of the exercise is to weed out illegal immigrants from Assam, which is a pertinent issue. However, the implementation has raised some red flags, with even the UN stepping in. In July, three special rapporteurs requested India to “review the implementation of the NRC”. They had earlier written to the Indian government, twice, but did not get a reply.

In its 2019 report, Human Rights Watch, the New York-based NGO, pointed out: “Throughout the year, the UN issued several statements raising concerns over issues in India including sexual violence, discrimination against religious minorities, targeting of activists, and lack of accountability for security forces.”

The world body also had choice words for the Indian government regarding Kashmir. In June, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights released its first-ever report on human rights in Kashmir. It spoke about human rights violations and lack of access to justice in the valley. The government dismissed the report, calling it “fallacious and motivated”.

Human rights in India have always been a complex issue, given the size, population and diversity of the country. And because they are inherently a complex web of ideas, and contain many parameters, there is no countrywise ranking for human rights. What we do have is data put out by the National Human Rights Commission, whose latest report, for the year 2016-17, recorded 91,887 cases of human rights violation; this was the lowest in the period from 2012 to 2017. While this might be a genuine improvement, the dip could also be because of underreporting.

Also read

- Indices: Where India stands in global rankings

- India's demography: All's not well

- Climate change performance index: India rank 11

- Poverty index: India rank 49

- Health care: India needs more doctors

- India needs to spend more to educate its people

- Liveability index: No Indian city in top 100

- Gender Gap: Unhealthy to be a woman in India

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the former adviser to a handful of US presidents, and the man The New York Times called the anti-Trump of American politics, once said, “The greater the number of complaints being aired, the better protected are human rights in that country.”

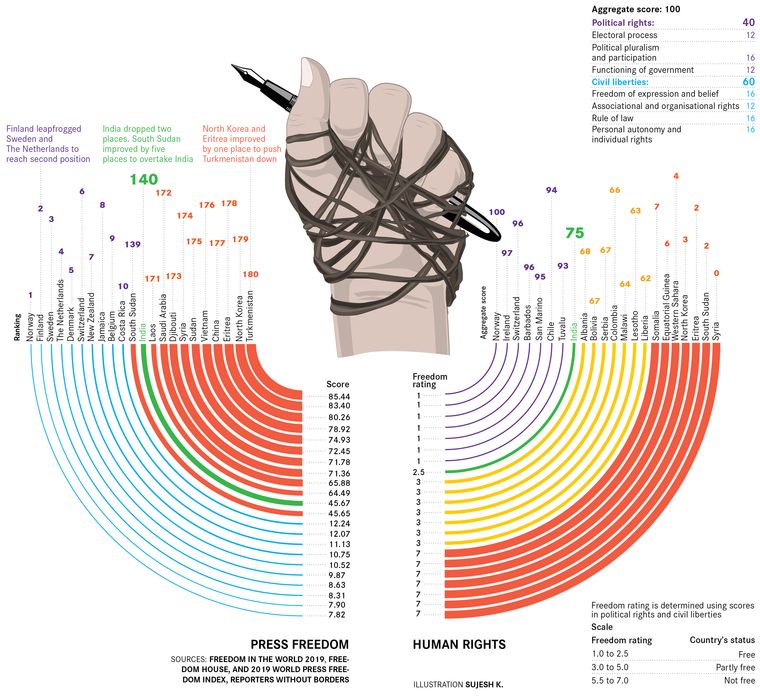

Given that journalists are the ones who usually “air the complaints”, press freedom becomes crucial to gauge the level of overall freedom in the country. In the Press Freedom Index, India ranks 140th of 180 countries, lower than South Sudan, Gabon, Chad and Zambia.

But all is not bleak. In April 2018, the Union government removed AFSPA from Meghalaya and parts of Arunachal Pradesh after 27 years. With insurgency at a long-time low, there are also plans to remove the controversial act from Assam, where it has been in place for 29 years.

That was not the only win for human rights activists. In September 2018, the Supreme Court, in a landmark judgment, decriminalised homosexuality by diluting Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, the British-era law that made “unnatural” sex (including consensual relations between two adults of the same sex) a criminal offence. Such steps, however, have been few and far between, and human rights in India continues to be a messy issue. Progress, it seems, is a work in progress.