CURFEW HAS OFTEN hollowed out Srinagar’s streets. Barbed wires have often punctuated every few kilometres of the troubled city. And snapped internet lines have been an invaluable weathercock, signalling the arrival of trouble. But this time, on a sunny August morning, as we clamber out of the airport—where a throng of tourists are waiting to leave and a flood of Kashmiris are coming back home, desperate to meet parents, children and spouses they have not been able to even speak to in several days—something feels distinctly different.

At the airport, one local resident describes it best. “Log sahme hua hai (people are scared),” he says, to explain the somewhat muted and quiet mood. If at other occasions, angry street processions have broken through security cordons and had head-on clashes with police and paramilitary, this time there is none of that. At least not yet. In fact, as we drive and walk around the city, there are more vehicles on the road than we thought we would see. At some street corners, kids are out playing cricket, and in front of closed shops with giant locks and downed shutters, small groups of men are huddled around talking and debating.

None of this is because there is widespread support or acceptance for the removal of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status, but because it does not seem to have sunk in. It is almost as if at least the Kashmir Valley never believed this day would come. The audacity of the decision by the Narendra Modi government, its suddenness, its circumvention of the constitutional amendment process, its deft skipping of the approval of the Jammu and Kashmir assembly (which is not in place because of president’s rule) and above all, its finality—there is a distinct shock and awe effect after the most dramatic decision in Kashmir in 70 years.

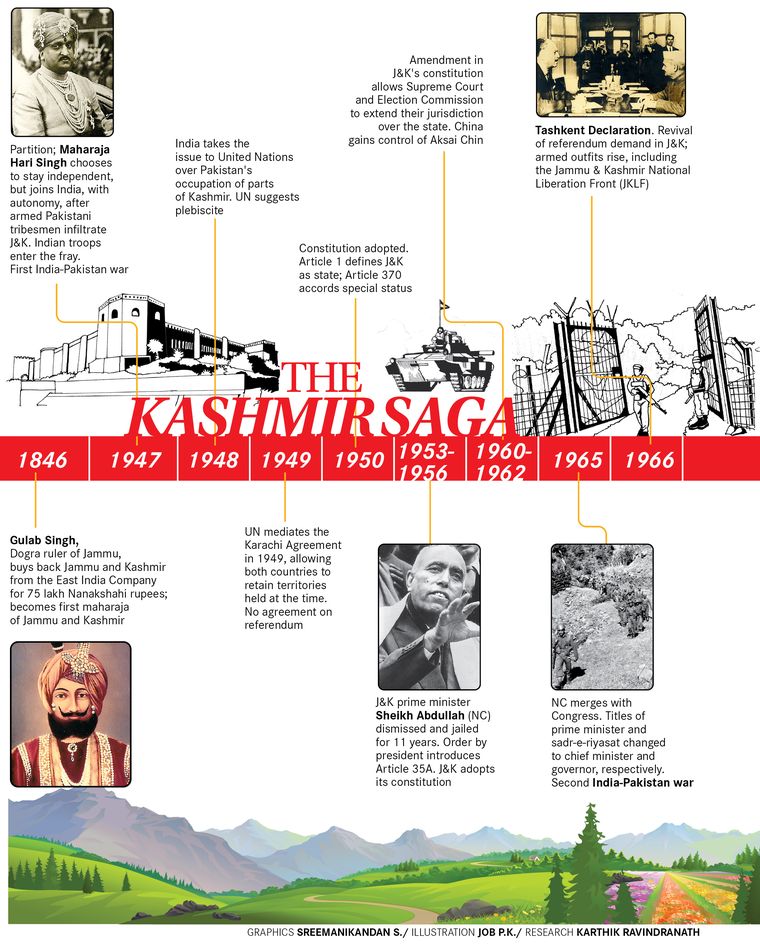

For several Kashmiris, Article 370, which gave the state—now a Union territory—a special place in the Indian Union, was more symbolic than substantive. People are aware that the powers granted to permanent residents and the state legislature have been chipped away at over the years, and done so by the Congress governments. For instance, in the 1960s the state lost the nomenclatures of sadr-e-riyasat (governor) and wazir-e-azam (prime minister). Now the governor will be a lieutenant governor and the chief minister, the mere head of a Union territory—vast swathes of which will be controlled directly by the Union government. But despite the weakening of Article 370 over the years, for many residents its continuance has remained a symbol of ethno-nationalism and parochial pride. “Yeh hamara taj tha (This was our crown),” says Roof Bhat, the taxi driver taking me around. “You have taken away our crown from us.”

Many others I meet echo the sentiment. Nasir Rather, who runs a fleet of cars, says: “This is the ultimate proof that Indians are only interested in our land and not us as people.”

The information blackhole—many channels are not accessible, even landline phone numbers are impossible to reach, there are no mobiles working and there is no internet—has created panic and rage. The arrest of mainstream Kashmiri politicians—Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti have been housed together at Srinagar’s Hari Niwas Palace, and Sajad Lone and Imran Reza Ansari at the Centaur Hotel—has raised further questions. The state director general of police, Dilbagh Singh, tells me: “We have made sure they are comfortable. They have only been detained for law and order reasons.” Singh emphasises the “zero violence” that has followed the removal of Article 370. “I will not make a political statement,” he says, “and maybe it is too early to judge what the situation will be, but there has been no spontaneous agitation in the valley, not even in south Kashmir. The people have cooperated.” When I push him on this point by pointing to the massive troop deployment, curfew, the internet restrictions and stalled social media platforms, he reminds of instances in the past when the same restrictions were in place, but there was much more volatility and strife on the streets. “The troop deployment is nowhere as high as has been reported in the media,” he says, “but think of other times when we placed exactly the same clampdown. Was the response not different?”

About this he is right. It is confusing to decode the muted response in Srinagar and the sense of fatalism that has followed the removal of the state’s special status. One explanation for this could be that usually it is separatists who have either led or nudged the street protests and clashes with security forces. Despite Pakistan’s expected statements and consequently predictable responses from the All Parties Hurriyat Conference, the fact is that separatists are hardly going to be at the forefront of protests in support of a provision of the Indian Constitution. By its very definition, those who have championed azaadi have refused to owe allegiance to the Constitution or to the Indian Union. So the sort of massive mobilisation that is often seen at encounter or operational sites, or at funerals of militants is hardly going to be replicated in defence of the Indian Constitution.

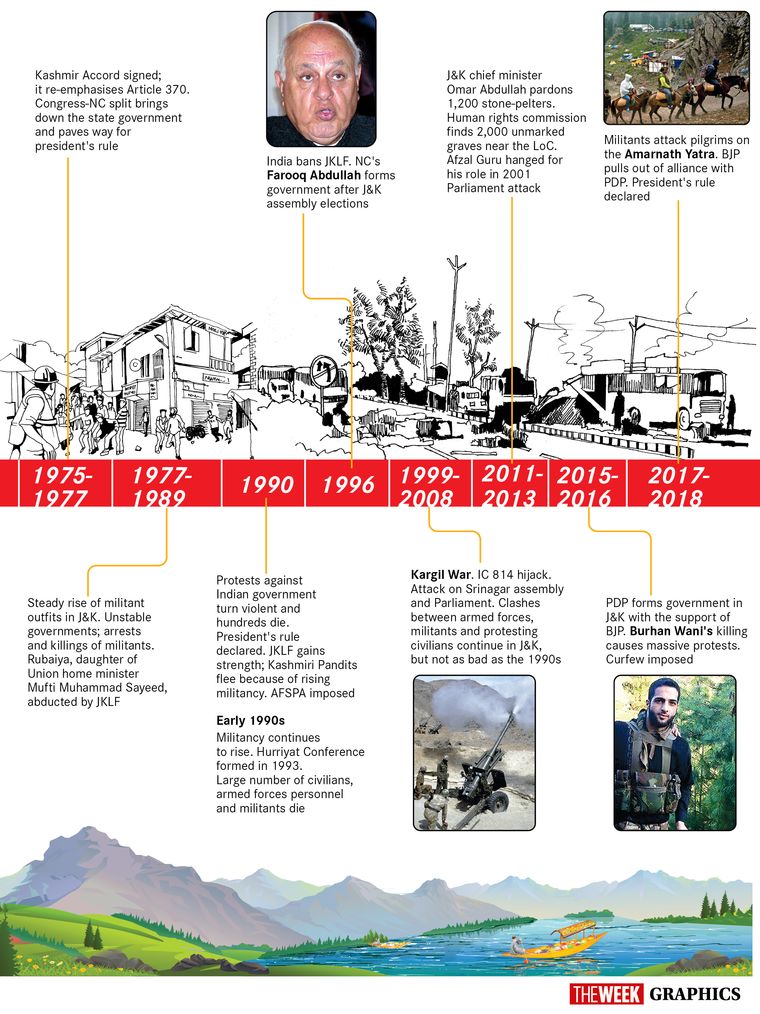

Article 370 and Article 35A are in the end more relevant to mainstream politicians than it is to separatists. And the mainstream parties today stand entirely marginalised. When I met Farooq Abdullah, the former chief minister and patriarch of the National Conference, he said that Kashmiri politics was “being reduced to zero”. On the streets, there is cynicism about whether these parties—the National Conference, the Peoples Democratic Party or the People’s Conference—shall be able to do anything at all. Near Dal Lake, a Kashmiri man scoffs at the question: “They cannot do anything. This question will now have to be decided by the people.”

The whispers on the street suggest that there is no political leverage available to the valley-based politicians and they will have no option but to cut a deal with Delhi. National Security Adviser Ajit Doval reportedly met Omar and Mehbooba in person, and asked for their cooperation. But there is no doubt that today they have been effectively placed in the same club as separatists. Many have been described as anti-national. As one Kashmiri resident told me on the request of anonymity, “Earlier Omar and Mehbooba used to send [pro-Pakistan secessionist] Syed Ali Shah Geelani to jail; today they are being treated the same way. What they did to others is being done to them.”

So while people in the Kashmir valley are disenchanted, they are also aware that there is no immediate leadership that can reflect their sentiments. Who exactly will mobilise protests even after curfew is lifted? That question should concern Delhi as well. While the BJP has scored a big political win in terms of domestic politics, tomorrow, should there be a dialogue process that has to be initiated in Kashmir, who will the government in New Delhi talk with? Mainstream politics has been shorn of its credibility and authority.

One of the most interesting comments came to me from a supporter of Geelani. He welcomes the fact that the fig leaf of mainstream Kashmiri politicians has been blown away. Now, he says, they will be compelled to play genuine politics.

What happens next in Kashmir may not be visible or apparent till Eid, when the restrictions are expected to be lifted. In the valley, there is often a lull before a storm and a single matchstick can start a forest fire.

Is there not an even greater danger of radicalisation, alienation and local militancy, I ask the police chief. “It all depends on how we conduct ourselves now,” he says. “We want to keep the peace, but we cannot be harsh with our own people.”

For answers to what next, we may have to wait a bit longer as Jammu and Kashmir charts a course of uncertainty and unpredictability.