About half of the global population above 14, i.e. 2.5 billion people, have smartphones. From 2000 to 2015, the world went from 400 million to about 3.2 billion internet users, including 2 billion from the developing world. In the 15-24 age-group, 71 per cent are online, while the world average is 48 per cent. Of 830 million youth who are online, 320 million (39 per cent) are in China and India. Simply put, the whole world, developing and developed, is going digital, and our youth are getting there faster. It’s not just smartphones; our cars, our cities and everything around us are being made smart by data-capturing sensors and internet connectivity. The net result of new users and new devices is an explosion of data. But why create so much data?

Data is the fastest and most accurate feedback mechanism known to man. Each individual human is a complex, nuanced decision-maker. But, at an aggregate level, with data from millions of users, we all fall on a curve. It also helps that the task of trend-spotting is now shifting to machines and Artificial Intelligence (AI), which are consistently proving to be better than humans at frequent, repeated cognitive tasks.

AI is challenging the notion of human intellectual superiority. Even quintessentially human tasks such as recognising objects, playing poker or making music are being proven as solvable with the right data. Turns out, our grandmothers were correct, practice does make perfect. Alas, the machines can practise a lot more, a lot faster than humans can. What fuels this rapid learning is our data.

Data has three properties that are worrying for consumer interest in the long run. First, data feeds itself in a virtuous cycle. More data helps create better products. Better products have more users, who in turn create more data. Harvesting user data for profit that is not fairly shared with the user is a new form of colonisation. Second, insights from data help companies outgrow traditional competition rapidly and establish dominance in their markets. Third, data is non-rivalrous, ie, the value extractable from data does not diminish when a second copy of the data is created. Yet, it is being hoarded to create exclusive deep profiles of users. These three properties create the triple threat of Data Colonisation, winner-take-all markets and eroding privacy.

This explains why every organisation, including traditional ones like GE and Philips, are creating platforms. Platforms provide simplified tools for building engaging products. They invest heavily in on-boarding new users. Even competitors are invited to build products on the platform. The quicker it grows its user base, the higher the staying power of the platform due to network effects. Most importantly, platforms capture and claim ownership of all data generated by user interactions on the platform.

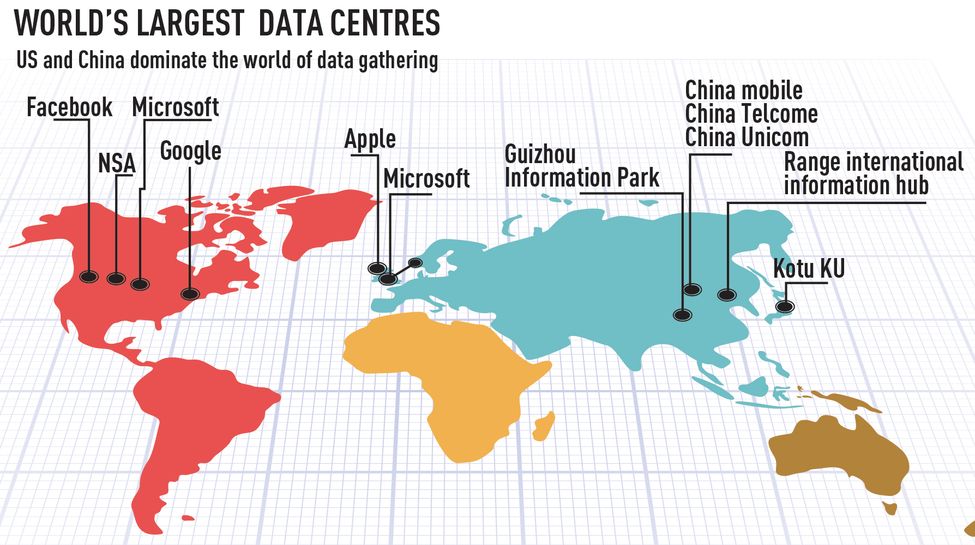

Platforms are able to squeeze every drop of value from data, because they keep it in silos. They analyse it to understand and disrupt adjacent markets. Already, four of the five largest companies in the world by market capitalisation are tech companies ousting three oil companies from that list. Even though data is non-rivalrous, it is not even shared with users who helped create it. This is a threat posed by domestic and foreign Data Controllers alike. China has shown that simply firewalling international firms will only create room for domestic ones to fill the gap.

Look at Facebook and Google. Together, they dominate about 71 per cent of the digital ad market in the US, and 89 per cent of its total growth. Or WeChat and AliPay which own 93 per cent of the $5.5 trillion mobile payments market (about 50 times the US mobile payment market, a clear leapfrog) leaving a meagre 7 per cent for the banks. Talking about entering adjacencies, Netflix made its first original content, House of Cards, in 2013. By 2017, Netflix produced 126 original films and series, more than any other single American network or cable channel. It was nominated for 93 Emmys, second only to HBO’s 110.

Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Alphabet Inc (formerly Google), once said, “Big Data is so powerful, nation states will fight over it.” Take Amazon: in 20 years, its revenue has grown exponentially from 0 to $100+ billion, yet it continues to flatline on profit, hovering close to either side of 0, focusing on growth instead. Tech companies understand the power of data better than anyone, and it would appear that their strategy is to take your data rather than take your money.

The triple threat of Data Domination is a policy issue affecting all countries in the world. The European Union is notifying the General Data Protection Regulation, a set of data protection measures placing extensive restrictions and penalties on Data Controllers. Similar protection and anti-trust efforts are under way in the US, Japan and even the UK. India doesn’t have a data protection policy yet, but can pioneer how a developing nation thinks about data. Our citizens will be data-rich in three years, and developing nations have most to gain from leapfrogging that data wealth into economic wealth.

Today, 2.5 billion people have smartphones. That also means that 3 billion people haven’t experienced smartphones yet. That’s 3 billion possible ideas for new ways to change the world, currently untapped. Even the 2.5 billion that have seen it, are still discovering what is possible with all the world’s information at their fingertips. In India itself, every second, three users experience the internet for the first time. Instead of simply asking how do we protect these new users, can we also ask how can we empower these users to use data for their own development?

To allow for empowerment, we must first take a very critical step: Inverting the data. Inverting the data is declaring the user the owner of her own data, empowering her with freedom and choice. It gives her the freedom to extract her personal data locked away in silos and choose to share it with another provider for her own development. In an inverted data scenario, a farmer can extract her digital footprints: call and sms records, bank statements, bill payments, agri input purchase data, electricity readings, etc, from disparate sources. She shares her data in a secure manner, without compromising her privacy, to get customised loans from new age lenders at interest rates she has never seen before.

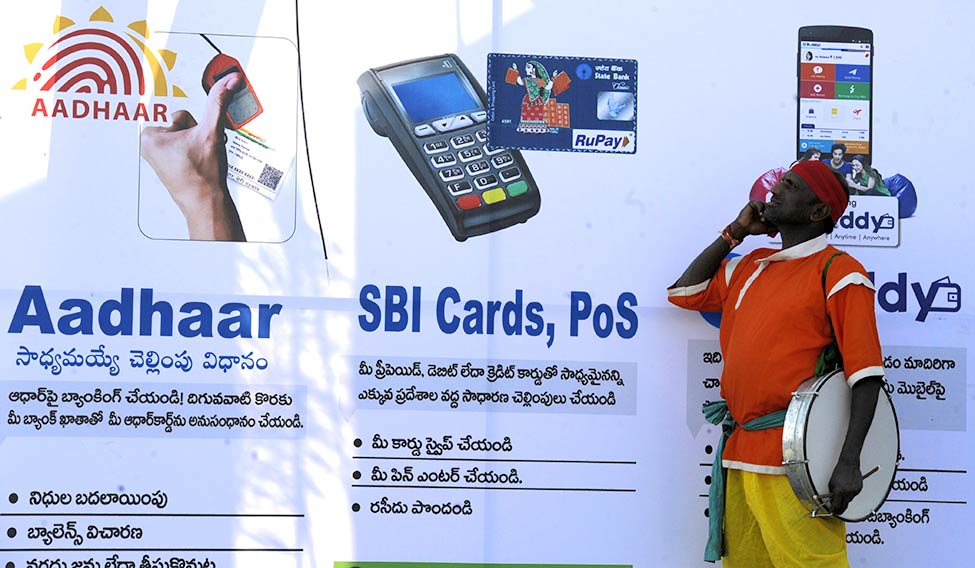

It’s not just a willing, savvy population; India is also infrastructurally uniquely positioned to implement Inversion. We have a billion users on the JAM [Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, Mobile] trinity for individuals and strong national-level platforms GSTN [Goods and Services Tax Network], BBPS [Bharat Bill Payment System] and UPI [Unified Payment Interface] for businesses. We are doing close to 40 million Aadhaar Authentications every day. The government has also developed the India Stack, a set of Open APIs that enable paperless, presenceless and cashless transactions dramatically driving down the cost of transactions. System designers can mix and match between OTP, Aadhaar Authentication and UPI PIN to create robust and secure authentication.

To complete Inversion, India must also take three simple, low-cost steps. First, we need to open up big government data sets for the public to consume. This includes data from national platforms such as GSTN and BBPS. Second, regulators need to open up the data sets in their jurisdiction in a standard, machine-readable format. Third, we need a data empowerment policy to allow for consented sharing of user data in the private sphere.

It is undeniable that data is power. If data accumulates in the hands of a few, then so does power. Inversion takes that power from the few and redistributes it to many; it is the universal suffrage of the digital world and hence the critical first step to a more representative internet. India can show the world that a country can choose to empower and not just protect its users through a policy of Inversion. In the 70th year of our constitutional democracy, as the boundaries between virtual and real worlds blur, let us ensure that India’s digital citizens also enjoy their right to self-determination in a Data Democracy.

Graphics: Deni Lal; Research: Neeraj Krishnan

Graphics: Deni Lal; Research: Neeraj Krishnan