Death came like a thief in the middle of the night when the storage tanks of the giant Rs 25-crore Union Carbide plant at Chola on the south-western outskirts of Bhopal, capital of sprawling Madhya Pradesh, started leaking deadly methyl isocyanate gas on December 2. Within minutes a thick fog had engulfed Jayaprakash Nagar, a vast slum which had sprung up in front of the factory, and the residents started coughing. First it was persistent coughing and irritation of the eyes and then thousands gasped for air as the deadly gas, a derivative of cyanide, deactivated the haemoglobin in blood.

At 1.30 a.m. a newsman of the Hindi agency, Hindustan Samachar, was woken up by the persistent ringing of his telephone. Thinking that it may be one of those crank calls, he took the receiver off the hook. Within minutes his daughter came with the news that a strange gas had started leaking out of the Union Carbide plant. He telephoned the police control. The officer on the line was the superintendent of police himself. "Run," he said, "and don't ask for any reasons. Just get your family together and run." Such was the panic that gripped Bhopal.

By 2.30 a.m. on Monday, December 3, Bhopal was in a panic. The dead lay unattended as thousands fled their homes into the cold countryside. In the heart of the city, the sprawling Hamidia hospital started getting its first patients while nobody knew what exactly was wrong. The company's officials refused to divulge what had happened. The factory authorities insist that the siren was sounded but they are not certain when this was done. The leakage started a little after midnight and it was reportedly plugged at 1.40 a.m. on Monday after nearly 30 tonnes of MIC had escaped into the air. Those living in Jayaprakash Nagar say that they did hear a siren but it was around 2 a.m. when the gas had already done its damage. Javed Khan, a private taxirowner, said that he heard the siren when he and 11 members of his family were fleeing in his tiny vehicle, "but by then the angel of death had already come."

Similar stories were heard from many of those who are undergoing treatment in Hamidia hospital. At the Amarpali Social Service Centre, Abida Begum insisted that she heard the siren at 3 a.m. when she had started vomiting blood. She was brought to the hospital before dawn. Over 500 people had been admitted to Hamidia hospital; Bhopal's other three hospitals were carrying their load as well. But the strange part was that the city's administration had collapsed; there was not one government official to release even the most elementary information about what happened.

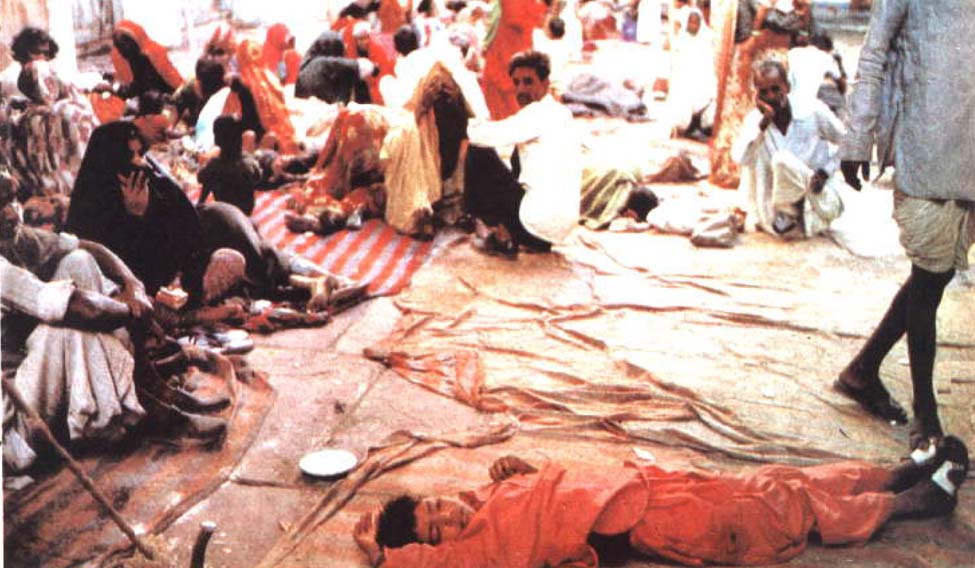

"It was like the scenes which I saw in films about World War II. Streets strewn with bodies and an exodus of people running for safety," commented a journalist. Men, women and children were running away from the city. Some escaped from the old city to the new city. Some walked, admirably enough even under such pressure, as long as 20 kilometres. But some failed to reach places of safety. They died on their way. The affluent rushed out in their vehicles. VIPs were the fastest to get out of Bhopal. At the railway station few survived. The station superintendent, Harish Durve, died in his chair in his room where the body of the booking clerk was also found. The control room had become a gas chamber where all the employees had fallen unconscious. All traffic had stopped and for eight hours the station was like a graveyard.

A pall of gas was over Bhopal followed by a pall of gloom. The tragedy took a toll of over 3,000 human lives and a similar number of cattle. Five thousand people were seriously affected and over 1,00,000 were taken ill. The majority of-the victims were children. A large number of pregnant women lost their babies. Many thousands became blind. The areas affected were Kenchi-Chola, Jayaprakash Nagar, Tila Jamalpura, the railway station and Chandwad. Here people had huddled together and died and there was no count of the number of the dead even as late as Thursday when things had come back to normal. In areas like Jehangirbad, Chotabazar and the surrounding suburbs, people fled. When reporters visited the heart of Bhopal on Tuesday, it was eerie: every door was locked and most streets were empty; only a few people were wandering aimlessly around.

Of Bhopal's population of 1 million (unofficial figure is 1.2 million) over 5,00,000 had fled in one night. The surrounding towns do not have the facilities to absorb such an exodus. Indore, two hours away, Dewas, Hosangabad. Obaidullanagar and other small towns were suddenly inundated with gasping and mostly dying people. In Obaidullariagar alone 40 people died on Tuesday and this was the official figure. The Union Carbide factory had become 'Yama' for the

citizens of Bhopal. Not that they did not have suspicions or fears about the chemicals being used in the plant. Earlier there had been cases of dangerous gas leakages from the factory. But the company's political clout and high-level influence had saved it every time. Ministers, who used to assure the people every time about the safety of the city, were the first to abandon it.

For many long hours there was no administration and none to help the unfortunate people of Bhopal. Perhaps one cannot blame the officials totally. For no one could even imagine such a catastrophe and the administration was ill equipped to face such a situation. People were left to fend for themselves. As they ran, some fell down and died. The majority of them were the poorest of the poor, emaciated, undernourished and with no resistance.

Those who were caught first were the slum-dwellers outside the factory complex. With them died their cattle as a number of dairies were located in the area. The gas was deadly. A few minutes of inhaling congested the lungs. After a shorter period of contact, one felt itching of the throat, eyes and stomach and then nausea. According to Professor Heeresh Chandran, who was in charge of the postmortem of the victims, the cause of death in most cases was pulmonary oedema. It was respiration failure due to collection of fluid in the lungs. The lungs of the dead had 250 to 300 cc of fluid.

In the hospitals thousands waited outside for medical aid. There were hardly enough number of doctors and nurses. There was not sufficient quantities of medicine the first day. Even the corridors were converted into intensive care units. A rope was tied from one end of the corridor to the other to hand saline and glucose bottles. While the hospital staff was finding it difficult to attend to thousands of serious cases, about 1,00,000 people with minor complaints thronged the hospitals for attention. The four medical institutions in the city, Katju hospital, .IP. Hospital. Hamidia hospital and Women's hospital, were forced to admit many more people than they could accommodate. Inside the hospitals the scenes were heart-rending. The cries of babies and screams of older people filled the air. On the first day there was hardly anything to eat. People even did not know whether they could drink water; none knew whether the poisonous gas had contaminated the water supply.

In their homes many people did not know whether they could eat vegetables and cereals. There was none to clear their doubts. In fact, the doubts persisted even after three days. What about the standing crops, many asked. "The experts are studying," was the answer.

By afternoon of the first day, as attempts were being made in the hospitals to revive the patients, efforts also were made to revive the collapsed administrative machinery. Chief Minister Arjun Singh, who denied having fled the city, announced the arrest of five top bosses of the Union Carbide factory. He also announced the decision to close the factory. He ordered a ]udicial inquiry and two days later it was made known that Justice N.K. Singh would head the commission.

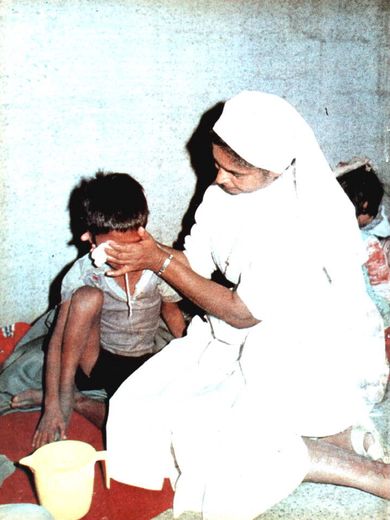

There were vultures- to take advantage of the tragic situation. Petrol prices touched Rs 25 a litre. Some private doctors overcharged. Auto-rickshaw drivers made a fast buck. But there were some shining examples too. Many voluntary organisations in the city, churches and gurdwaras came out to assist. Students, NCC boys and girls, the Girl Guides and Scouts were in the hospitals arid residential colonies offering help. Bread, milk and fruit were brought in for the victims. Even mohalla committees were formed to organise aid on a vast scale.

The second day saw a somewhat better organisation in the hospitals: 600 doctors and nurses from nearby district hospitals were summoned to help the local staff. Some specialists from New Delhi were also brought to Bhopal by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. But the problem on the second day was the disposal of the dead. Hundreds of bodies were unclaimed in Hamidia hospital. Thousands queued up to identify the bodies. Many poor people could not claim the bodies as they did not have the money to do the last rites.

Bhopal's divisional commissioner then had a bright idea. He reportedly asked the municipal commissioner to cremate 350 bodies together at the Vishramghat ground which is ironically close to the factory. The Municipal Commissioner requested the city engineer to persuade the committee in charge of the cremation ground to agree to the "proposal." He showed the commissioner's note to the committee in the presence of an MLA. The committee refused to give any written permission. Instead it asked for a photograph and death certificate of each body. It was obvious that the relatives had won.

The area surrounding the Union Carbide factory could be spotted easily from a distance as vultures were hovering over it. Hundreds of buffaloes were lying around. It was tragic that the caste system operated even when Bhopal was facing such a tragedy. There were few people to remove the bodies as members of that community who normally did the job were affected by the gas. Chief Minister Arjun Singh himself admitted the shameful situation. He said that 'people who remove the bodies of dead cattle' were being brought to Bhopal from nearby towns and villages.

On the second day the rush to the hospitals increased. Unable to cope with the crowd, tents were pitched on the hospital lawns, thanks to the timely help of the Indian Army. Volunteers were seen assisting the nurses and doctors by carrying serious patients on stretchers and distributing medicines. State transport buses, corporation trucks, jeeps, three-wheelers and cars carried patients to the hospitals and bodies to the cremation grounds. By afternoon the voluntary force was reinforced by sisters of Asha Niketan, workers of political parties, and members of Bhopal Jaycees, Lions Club, etc. At the factory, sleuths of the CBI began interrogation of members of the staff and experts of the Government of India and state government began deliberations on the next step. The second day also saw the visit of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to the city which activated the administration. He announced grants of Rs 40 lakh from the Prime Ministers relief fund and Rs 5 lakh from the Congress(I) which gave the state government some hope.

Rajiv Gandhi went straight to Hamidia hospital to console the ill. To most of them his coming was a blessing in disguise. Medicines which were mostly absent on Monday suddenly made their appearance.

By the third day, the city slowly started limping back to normalcy. the administrations decided to destroy the 30 tonnes of gas that remained ad asked experts to find a way to do this. The factory's experts are reported to have said that it would take them three weeks to do this. But when the gas escaped, 30 tonnes of gas had escaped in two hours. The state government which was always shy to deal directly with the Union Carbide factory, appointed an inquiry commission, a committee to work out the compensation issue and another committee to plan rehabilitation work. The government is also reportedly planning to file a damage suit for 15 billiob dollars (Rs 1,800 crore) in a US court against the company. With three committees having been appointed, unpleasant queries could be evaded with stock answers like "a commission has been appointed" or "the committee could look into everything.'

The Governor, K.M. Chandy, returned to the city from Bombay on Wednesday. In the hospitals, relief money was distributed, Rs 500 for those taken ill, Rs 1,000 to those who are seriously ill and Rs 10,000 to the families of those killed.

The collapse of the administration in the first two days was such that none knew how many were killed. So much so that by the third day, newsmen who had checked with cremation and burial grounds had more accurate figures of those killed than the state administration. Even then few people knew what immediate steps should be taken if affected by gas. But by the third day, an alert information department put up advertisements and made All India Radio make announcements on the dos and don'ts if suffering from gas poisoning.

The pathetic aspect of the incident was that even days after the incident none knew in Bhopal the long-term effects of the poisoning. The treatment given was for the symptoms, a fact which was painfully admitted by V.P. Sathe, minister ofr chemicals.

In any other place, such an incident would have resulted in the rolling of some heads responsible for the tragedy. But in Bhopal, only five executives of Union Carbide were arrested and allowed to stay in the factory premises to help run the plant and be of assisstance should any emergency occur.

Had such tragedy happened in the US, Union Carbide would have been worried about its survival. For in the USA, the compensation to be paid for such victims is high and the law and courts are very severe on such lapses. The company did not have to worry on that count about the Bhopal tragedy. Moreover, the state government has appointed a commission to negotiate the compensate terms. It was indeed a welcome development for the company as an out of court settlement would be simpler and less expensive. However, to be fair. Chief Minister Arjun Singh made it clear that the appointment of the committee would not affect the process of law. He said that the law would lake its course. According to legal experts, even then there was nothing much for Union Carbide to worry as the laws in India are not as stringent as in the USA, especially in the case of compensation.

In the first week of December, there was only one state capital in India, which was not affected by election fever all over the country. Yet. there were discussions on the impact of the tragedy on the elections. Chief Minister Arjun Singh called for senior friendly journalists and requested them not to "'blow up" the issue at this juncture. However, in Bhopal the mood was transparent. The state capital, which is a stronghold of the Congress(I), was no longer congenial for the ruling party whose main worry was that the opposition would try to make an election issue of the tragedy. The party's fear was that if the role of multinational companies and the part their executives play are blown up, that may cause inconvenience to people like Arun Nehru, general secretary of AICC and Arun Singh, parliamentary secretary to the Prime Minister, who both joined politics leaving their jobs with multinational organisations.

However, in Bhopal there was no big effort by the political parties to exploit the issue for election purposes. There were reasons for this. The tragedy that struck Bhopal was far too serious. There was no place in such circumstances to take up narrow political issues. Indeed Bhopal has raised some other far more serious issues which will have their impact on the industrial and environmental life of India. In industry a fresh study of the functioning of multinational companies is the immediate demand. Whether multinationals ignore the safety standards practised in developed countries is a serious question. Indeed N.K. Singh will study this at length. If multinationals have double standards in their operations, even on such crucial aspects like safety measures, a fresh policy towards multinationals will indeed be justified.

At the same time there is another aspect. No development is worth if it is to ignore life itself. In this context the relevance of environmental aspects cannot be minimised. In any case the policy to locate factories producing dangerous chemicals at remote places needs to be strictly enforced. Human error and failure of machines cannot be controlled. Such cases will be repeated whether the machinery is sophisticated or the men handling it is experienced and efficient. What is needed is to keep such factories away from habitation. The costly lesson of Bhopal should open the eyes of the administration in the country: if ignored, it can only be at our peril.