At a time when the watchmaking world was grappling with the Quartz Crisis, one man dared to risk it all. He pursued his dream of preserving the art of mechanical horology. Michel Parmigiani was undeterred by the growing popularity of quartz watches and started his own workshop in 1976, specialising in restoration of vintage timepieces made by other established brands.

By then, the Quartz Crisis was well-entrenched in its fifth year and many naysayers had written off the future of Swiss timekeeping. But, perseverance did pay rich dividends. Parmigiani Fleurier, despite being a young player, made a mark. WatchTime India travelled to the manufacture units based in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Fleurier and the Jura region of Switzerland to get a perspective on restoration—the genesis of the brand. And how it achieved independence.

Michel, 63, was born in Couvet in the Val-de-Travers, a region known for watchmaking. It was natural for him to veer towards this field. If not a watchmaker, he would have been an architect because of his creativity, curiosity and interest in history, says the Swiss doyen.

“There was a statue of Ferdinand Berthoud, the famous 18th century chronometer maker, in the middle of my village, and I would always pass by and look at it with fascination,” says Michel. “The first watch I possessed was a gift from my father, and I took it apart and reassembled it because I wanted to see how things looked inside.”

A watchmaker restores a pocketwatch at the Parmigiani workshop.

A watchmaker restores a pocketwatch at the Parmigiani workshop.

He started off restoring artefacts, and later, set up his own unit, Mesure et Art du Temps in 1976. “Despite the Quartz Crisis at its peak, when around 90,000 people lost their jobs, I decided to go forward with my plans,” says Michel. “If you had seen as many watchmaking marvels as I had, through my restoration work, you wouldn’t have believed that traditional watchmaking would end just there. Restoration gave me faith in the knowledge that mechanical timepieces would not be lost to the profit of quartz.”

It was the year 1980 that changed it all. Michel came in touch with the Sandoz Family, which backed him in establishing his own brand. The Sandoz Family is heir to the Sandoz pharmaceutical group known today as Novartis, and possesses some of the most impressive collections of pocketwatches and automata in Switzerland.

“Parmigaini was born in 1996. It would not have existed as it is today had it not been for the Sandoz Family,” says Michel. “Since the inception, we have built around the brand a fully verticalised manufacture that can supply any piece of a watch, from the smallest screw to the most intricate dials.” Today, Parmigiani employs about 600 people.

To make the brand self-reliant the Sandoz Family acquired five production units—Atokalpa, Les Artisans Boîtiers (LAB), Vaucher, Elwin and Quadrance et Habillage— collectively known as Manufactures Horlogères de la Foundation, which are like sister-brands and were set up in less than four years to make up Parmigiani’s self-reliant watch business. Says Benoith Conrath, a watchmaker who has been with the company since the beginning: “These five units are like fingers which form a fist, and, similarly, these independent entities are put together to further Parmigiani’s growth.”

The roles of these five factories are clearly demarcated. Atokalpa, acquired by Sandoz Family in 2000, manufactures gear trains, pinions and micro-gears. It is situated in Alle in the Jura Mountains. The same year saw the acquisition of one of the most renowned workshops in the high-end case production industry—Bruno Affolter SA, in La Chaux-de-Fonds, known as Les Artisans Boîtiers or LAB for easy reference.

The Cat and Mouse automaton clock.

The Cat and Mouse automaton clock.

Spread over 1,260 sq.m, this facility is equipped with the latest machinery that uses 3D computerised construction, (CAD) followed by CNC machining to produce cases. “It’s here that we have also produced and supplied cases to other brands like Zenith, Corum, Graham, Greubel Forsey and Girard Perregaux,” says Conrath.

Vaucher, another unit based in Fleurier, is the heart of the Manufactures Horlogères de la Foundation. Set up in 2003, this is where movements are produced and, thanks to this unit, Parmigiani Fleurier has developed six collections and 27 in-house movements.

“Vaucher is an independent entity and can supply to whoever it wants, but it was created specifically for Parmigaini first and opened up to 17 brands later for ensuring long-term survival in the industry,” says Conrath. Brands such as Richard Mille take 80 per cent of their movements from Vaucher.

“Last year, 22,000 movements were made at Vaucher, of which, 5,500 were for us and the rest for Corum, Bulgari, Richard Mille, Harry Winston and Hermes,” he says. “This is in no way a hindrance for our growth because we are entitled to supplies as and when we wish. Also, the calibres are customised for each brand so there is no question of overlapping.”

The movement-manufacturing process, in a nutshell, starts with the preparation of the base plate from brass using CNC machines. Then it goes to another department for step by step stamping of some parts. After this, the movement is sent for polishing, engraving and electroplating. It’s interesting to note that, unlike many brands, Parmigiani movements are machine-engraved and not by hand.

However, the matting is done by hand. “This process takes about three hours, and each movement goes through this because, as a policy, we are opposed to shiny movements,” says Conarth. “Michel believes that the watch needs to look as beautiful on the inside as it is on the outside. We spend at least a day on just decorating the movements. However, we don’t hand-engrave them because we have realised that it causes a lot of trouble when the watch is assembled.”

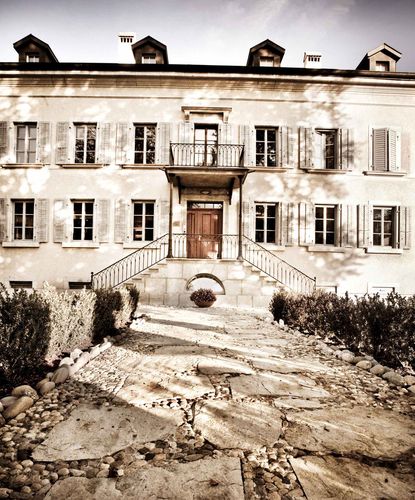

Parmigiani headquarters in Fleurier, Switzerland.

Parmigiani headquarters in Fleurier, Switzerland.

Elwin, the fourth pillar of the brand at Moutier, was created in 2001 by the third generation of a line of industrialists who have been specialising in bar turning for watchmaking (mainly balance staffs) since 1912. Its role is to produce high-precision components for Parmigiani. Eleven highly qualified staff slog it out at its 1,700sq.m production site, which opened in June 2010.

Parmigiani achieved complete independence by mastering the art of dial production. For this, Quadrance et Habillage was created in December 2005 and integrated into the Manufactures Horlogères de la Foundation. ‘Habillage’ means ‘closing’ in French, and the nomenclature stems from the fact that no watch is complete or ‘closed’ without a dial or face. This unit located in La Chaux-de-Fonds, ensures Parmigiani’s complete autonomy in dial manufacturing.

Here, the dials are stamped using CNC machines and sent for finishing or sand-blasting. They are then fixed on a tray, hand-brushed and gilded. After this, the dials are mounted on cage-like stands with hooks and immersed in a chemical solution for colouring, using lacquer or galvanoplasty. Then they are sent to artisans, who apply the indices by hand.

The watches are assembled in Fleurier. Once all the components are procured from the individual units comprising Manufactures Horlogères de la Foundation, they are sent to Ateliers Parmigiani, where 10 people put together these timepieces. The facility has big windows, as the watchmakers should look out into open space since they have to sit long hours at their desk and handle minute components, which can cause blurred vision.

The design department plays a crucial role in case of high-end watch manufacturing. While Jean Marc Jacot, the CEO, is personally involved in the design aspect at Parmigiani, Michel focuses on the restoration unit and movement creation. Once Jacot approves the designs, five skilled designers take care of the creative requirements.

Alexia Steunou, a senior designer who has been working with the brand for six years, says that it is extremely important for them to ideate, rather than work on someone else’s ideas. “We have to follow the brief given by Jacot and interpret his feelings about market trends when designing a new watch,” she says. “We work on a number of sketches depending on the brief and then he chooses the final designs. The designer of a particular watch is also responsible for the shape of the case, dial and even the bracelet.”

Alexia designed the Bugatti Super Sport watch and The Cat and Mouse in 2010, which, according to the brand, are “pieces of exception” or “high complication”. The Bugatti Super Sport was the next watch after Bugatti 370, created with the purpose of reading the time better on the wrist while driving.

The ‘pieces of exception’ are Parmigiani’s strength. One can easily draw parallels between them and the automata produced for the nobility during the Victorian era. This has been possible because of the founder’s love for history and the requisite know-how. They are priced at about CHF 1 million each.

“For The Cat and Mouse, I did not use my computer; all the sketches were hand-drawn,” says Alexia. “We developed this on the concept of an automaton where it turns one round for an hour and, in that period, it tries to catch the mouse six times. The idea is very simple but to reproduce it was complicated. I observed my pet cat and clicked lots of pictures to bring authenticity to the movements.”

Parmigiani, despite becoming a global luxury player, still seeks inspiration from restoration, which forms the backbone of the company. Restoration has helped the brand immensely in imparting an exotic flavour to its designs, which have clicked with watch collectors.

Currently, there are about 10 watch restorers in Switzerland, but few of them are at par with Parmigiani. It takes about a year to restore a watch, depending on its condition. According to Michel, the toughest timepiece that he has ever restored is The Magician pocketwatch belonging to The Patek Phillipe Museum. The factory employs only six artisans, as not many people have the requisite expertise. The restorers go through a strict selection process followed by a two-year programme in restoration. This training is in addition to the mandatory four-year course in watchmaking.

Michel feels that the autonomy in terms of component production and design has been the best thing to have ever happened to Parmigiani. “Our aim is to make watches that last a lifetime without compromising on the Swiss quality and ethics,” he says. “We are working towards achieving a 50-50 ratio for our men’s and ladies’ watches, which currently comprise 35 per cent of our volume. This will only happen once we reach the target of 10,000 movements in the next five years.”