It was, indeed, a midnight knock. It took me some time to open the door since the air conditioner in the room had drowned every other noise. I was not surprised to see the police. Nikhil Chakravartty, editor of Mainstream, had warned me that they might search my house. The warrant of arrest was not what I had expected.

Why the arrest? I searched for an answer. Was it because of the letter I wrote to prime minister Indira Gandhi? Or, was it because of the resolution I had got endorsed by journalists at the press club in Delhi to condemn the Emergency? Whatever the reason, I was not mentally prepared for the arrest. Even Chakravartty did not know from his well-connected sources that my name was among those to be arrested.

I recalled that I was sitting in my cabin at The Indian Express office when a staffer returned after covering the press conference of Indira Gandhi. This was the day after the imposition of the Emergency. The staffer read from his notes the sarcastic remarks Mrs Gandhi had made: “Not a dog had barked!” She had caustically referred to the editors who had given headlines against her.

That she did not know the working of newspapers was understandable. But her running down the editors was intentional. They had demanded her resignation after the Allahabad High Court had disqualified Indira Gandhi as an MP for six years for having used state machinery during her election campaign.

Instead of stepping down, she suspended the Constitution, imposed press censorship and restricted personal freedom. More than 1,00,000 people were detained without trial and all the opposition leaders, including Jayaprakash Narayan, who had led the movement against her corrupt government, were put behind bars. Worse still was the destruction of institutions, which still have not regained health.

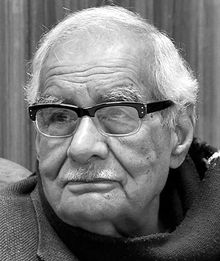

Illustration: Binesh Sreedharan

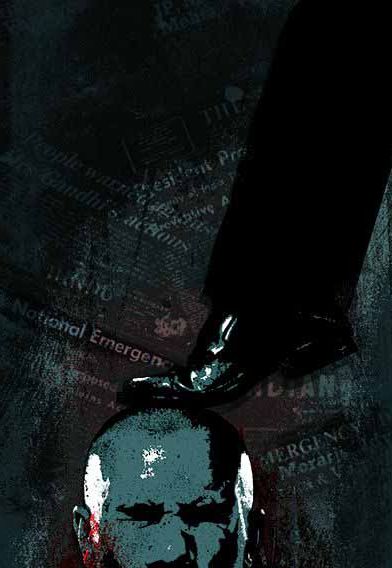

Illustration: Binesh Sreedharan

In the evening, I went to some newspaper offices to pass the word that there would be a meeting the following day at the press club. To my surprise, the conference hall at the press club was full. Among those present was Girilal Jain, resident editor of The Times of India. I read out the resolution I had drafted to condemn the Emergency and the imposition of censorship. One journalist mentioned that some editors had been detained. I told the journalists to sign the resolution. I said I would forward it to the president, the prime minister and the information minister under my signature.

As many as 103 journalists signed the copy, which I had placed at the entrance of the press club. I took the copy along, lest it should fall in the hands of the police. Hardly had I reached home when V.C. Shukla, till then a friend, rang me and asked if I could drop in at his office. I was shocked to find a different Shukla, authoritative in tone and threatening in posture. He asked me to give him the paper the journalists had signed. When I said 'no', he warned me that I could be arrested. “You should understand it is a different government, run by Sanjay Gandhi, not Indira Gandhi,” he said.

It was true that Sanjay Gandhi, an extra-Constitutional authority, was literally running the government. Mrs Gandhi had sheepishly withdrawn in his favour. As far as I was concerned, Sanjay Gandhi had ordered my detention. The owner of The Indian Express, Ramnath Goenka, had warned me that he did not know what they would do with me. He said he had gone around the Congress and official circles and had found that they wanted to punish me for having “supported the JP movement”.

To my mind, I was jailed for the letter I had written to Mrs Gandhi after the imposition of the Emergency. The letter said: “...Madam, it is always difficult for a newspaperman to decide when he should reveal what. In the process of doing so, he knows he runs the risk of annoying someone somewhere. In the case of the government, the tendency to hide the truth and feel horrified once the truth is uncovered is greater than in any individual. Somehow, those who occupy high positions in the administration labour under the belief that they―and they alone―know what the nation should be told, how and when, and they are annoyed if any news which they do not wish to be revealed appears in print.... In a free society―and you have repeatedly said after the Emergency that you have faith in such a concept―the press has a duty to inform the public. This is sometimes an unpleasant task, but it has to be performed because a free society is founded on free information. If the press were to publish only government handouts or official statements, to which it is reduced today, who will pinpoint lapses, deficiencies, or errors?”

I was in jail for three months. The court accepted the habeas corpus petition that my wife filed. Justice S. Rangarajan, heading a two-judge bench, passed strictures against the police for having arrested a person who belonged to no political party and carried out his journalistic duties independently and professionally. The government was unhappy with the judgment. Justice Rangarajan was transferred to Sikkim and Justice R.N. Aggarwal who was part of the bench was reverted to the sessions court, from where he had been elevated. The two judges were sacrificed at the altar of press freedom.

Nayar is a journalist and former Rajya Sabha member.