At 6:59am, on March 30, A. Ashique updated his Facebook profile picture. With a hashtag “Gone_with_the_wind”, he put up emojis of a person walking, along with the text “soon II end”. His friends thought he was referring to the end of his undergraduate course—the college farewell was on that day.

Ashique “liked” the comments on the post till 9:16am. Then he stopped reacting. The positive comments continued till 3:42pm, but a few hours later, they gave way to crying emojis. Instead of attending the farewell, he hanged himself from the ceiling fan in his bedroom that evening.

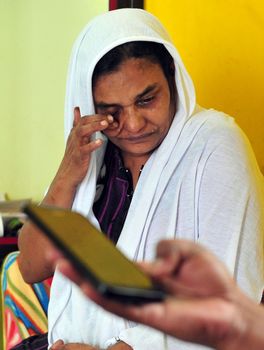

An “unusual death”, said the police, closing the case. In August, after a Mumbai teen jumped off a building and died, possibly incited by an online phenomenon known as the Blue Whale Challenge, Ashique’s death made news again. His mother, Asma Bi, 41, voiced the suspicion that he had fallen prey to the challenge.

THE WEEK met her at her home in Palakkad, Kerala, on August 21. She was forlorn, desperate to hold on to the one explanation that made sense to her.

She had seen the news, she said, and had noticed similarities in the behaviour of her son and of the other alleged victims of the Blue Whale Challenge. Ashique, 19, left home at unearthly hours, visited a nearby cemetery and was glued to his phone. “When I asked him about the cuts [on his body], he said it was part of a game,” said Asma Bi. “Our neighbours spotted him standing on top of the house in the middle of the night. When he was caught sneaking off to the cemetery, he told me that going there gave him an energy.”

Like some of the other suspected Blue Whale victims, Ashique, too, was an excellent student. But, growing up without a father had been tough on him, said Asma Bi. “His father deserted us when I was three months pregnant with Ashique,” she said.

Happier times: Manoj (in red shirt) with his family. Anu (first from left) blamed the Blue Whale Challenge for her son’s suicide.

Happier times: Manoj (in red shirt) with his family. Anu (first from left) blamed the Blue Whale Challenge for her son’s suicide.

The day before his suicide, the family had gone to attend a wedding in Coimbatore. Ashique returned early the next day, saying that he had to go to his college farewell. When Asma Bi reached home at around 4:30pm, she found the door locked from inside. Ashique did not answer the door. Thinking that he was asleep, she went around and opened a window that had a faulty latch. “I thought he was standing on the bed,” she said, her eyes moist with tears. “He had his earphones on and I thought he could not hear me. But, then I noticed he was not moving at all, and that is when I looked up and saw that he had hanged himself with the bed sheet.”

Composing herself, she played a recording of a call on his phone—it was his last conversation. His friend Arjun (name changed) had called him to check why he was not at the farewell. In the six-second recording, Ashique could be heard crying and saying that he did not want to live.

“He was always moody,” said Arjun. “He used to say he missed his friends from school and that after graduation he was going to miss his college friends. This upset him. When he was not upset, he was active and jovial.” Arjun said Ashique had never mentioned the Blue Whale Challenge to him. The suicide came as a surprise to him.

Amala A.K., head of the commerce department at Government Victoria College, Palakkad, said: “He was motivated and disciplined. He got good marks even in the final semester exams he took before committing suicide.”

Game and gore: Harindran N.V. and Shaki, the parents of Sawant, who they say committed suicide because of the challenge; (right) Sawant cut his arm, reportedly for the challenge | Prasanth Pattan

Game and gore: Harindran N.V. and Shaki, the parents of Sawant, who they say committed suicide because of the challenge; (right) Sawant cut his arm, reportedly for the challenge | Prasanth Pattan

To address Asma Bi’s concerns, the police have launched a further inquiry into the case. An officer privy to the investigation told THE WEEK that they had no major leads. “The postmortem report said there were no external wounds other than the abrasion around his neck,” he said. He noted that Ashique had not kept himself aloof from his friends any time, something that did not match Blue Whale stories.

Asma Bi has no doubt that the Blue Whale was behind his death. “Some people said it was a failed romance,” she said. “But, my son was not like that. He never went after any girl. Some cruel people made this game and my son fell victim. He was my last hope.”

The azaan for midday prayers interrupted her. She continued to shed silent tears. The mother had lost her first son, Mohammad, when he was two. Ashique truly was her last hope.

The Blue Whale Challenge, now swimming in the Indian psyche, reportedly originated in Russia in 2013. It is apparently named after beached whales, a phenomenon of whales killing themselves. It is, strictly speaking, not a game, but an online community, where members are told to complete a task (mostly involving self harm) every day, for 50 days. Participants are told to submit photos as proof. Apparently, the last task is to take one’s own life.

Asma Bi

Asma Bi

There seems to be an amorphous group of people on the internet who operate the challenge. It is not a downloadable app or software. The group is said to reach out to at-risk teens through social media. Willing participants can also contact them, covertly, using certain links. Once inducted, each participant is assigned a curator, who hands them the tasks.

The tasks are progressively violent. They start off simple—wake up at an odd hour, watch a horror movie or dance to a specific kind of music. Soon, the players are asked to cut themselves, climb buildings and, finally, commit suicide.

The curators are reportedly experts at brainwashing, creating a sense of despair in the participant and getting private information from them, which is later used to blackmail reluctant players into continuing the challenge.

Philipp Budeikin, 22, reportedly created the community, called F57, through Vkontakte, Russia’s version of Facebook. Budeikin, who pleaded guilty to inciting at least 16 teenagers to commit suicide, told the police in May that he was “cleansing the society” of “biological waste”. He reportedly created a psychological test to screen potential participants. Globally, the game is said to have claimed about 130 lives.

In India, at least six suicides have been linked to the challenge, three of them in Kerala. After Ashique’s death in March, Sawant, a 22-year-old draughtsman in Thalassery, Kannur, hanged himself from a ceiling fan on May 19; his chest and hands had cuts.

“I have lost my only son,” said his father, Harindran N.V., who broke down on the phone. “People are saying that the Blue Whale Challenge killed my son…. I have not seen a blue whale,” said Harindran, who is a driver. “All I know is this Blue Whale has killed my son. I don’t know how to console his mother, whose tears refuse to dry up. Every time someone talks about Blue Whale, my life comes to a standstill.”

For a few weeks before he died, Sawant always carried his smartphone, not at all an odd behaviour for a techie, said Harindran. “He had started going out at night, saying he had to meet a friend or attend a wedding.” His mother, worried, told him to sleep next to her. One night, the parents woke up to find him missing. “We found him at a bridge,” he said.

Apparently, Sawant was the go-to guy for computer-related issues in his neighbourhood. “We never said no to any of his wishes. He was especially attached to me,” said Shaki, his mother. “But, he became moody and irritable in the past few months. I used to see lights in his room even at three in the morning. When I asked him about it, he shouted at me.”

They took Sawant to a psychologist, who said he had symptoms of depression. He was asked to spend less time on his phone and computer.

“I saw him playing it [the Blue Whale Challenge] and heard him talking about it,” said Shaki. “But, I did not realise that he was inching towards death.”

Harindran connected his son’s death to the challenge after he heard the story of Anu, the bereaved mother of Manoj C. Manu, of Vilappilsala, Thiruvananthapuram.

A software engineer, Anu told THE WEEK about a conversation she had with her son: “Blue whale? What a name for a computer game! In future, games might be named after sardines, too,” she had joked when Manoj told her about the challenge during a chat in their kitchen. When he told her about the last step, Anu was shocked. She made him promise that he would not play it again. The promise was not kept. Manoj hanged himself on July 26. Anu is a software engineer. She said Manoj had shown behavioural changes over the past few months. First he scratched the letters “A B I” on his right hand. “I cried and made him promise not to do it again. I asked him whether those letters stood for a girl’s name, but he denied it,” she recalled.

He stayed up late, became easily agitated and started locking his bedroom door. He also started visiting cemeteries to “test his own courage”. He told his mother not to worry if he died, and to give all her love to his sister. “I cried, but I never thought he meant it,” she said. She said he had written in his diary—which she saw after his death—that somebody was threatening him. She said he was unusually happy the day before he took his life. “His father and I were happy to see him smiling after a long time,” she said.

Sub-inspector K. Kannan said the police had sent Manoj’s phone and laptop for scrutiny. “His parents believe the suicide was because of the Blue Whale game. We are yet to get any clues regarding that,” he said.

The police in Kerala, in fact, do not buy the Blue Whale theory. “We are yet to get any evidence to link these deaths and the game. But, the one thing we are sure about is that Manoj and Sawant were prone to depression,” said Inspector General Manoj Abraham, who is the nodal officer of Cyberdome, a technological research and development centre. No “normal” teen would play the game, he said; only depressed persons would seek out the link to the challenge, if there was one.

Abraham said the police were yet to get any trace of Blue Whale curators. “After [the arrest of Budeikin], there have been no confirmations of the game. So, it is almost certain that the game is not the reason for the suicides.”

Cyber forensic expert Vinod Bhattathiripad, however, said, “The police seems to be in a hurry to negate the existence of the game, which has been confirmed in many countries, including Britain and Russia. The police have not even completed their forensic report while arriving at this conclusion.”

On August 12, Ankan Dey, 16, of Keshpur in West Bengal, was found on the bathroom floor, a polythene bag wrapped around his head and a nylon cord lying nearby. At noon, he had asked his mother to prepare food and had gone to take a bath. He never came out.

His father, Gopinath, who runs an electronic goods shop, had told the police that the class 10 student had been addicted to computer games. Police Superintendent Bharati Ghosh, however, said that there was nothing to suggest that the boy died because of the “deadly game”.

Keshpur panchayat president Subhra Sengupta, who is a relative of the boy, told THE WEEK: “It is an entirely false claim that the boy died because of the challenge. I checked his body and found no injuries that occur in games like Blue Whale.”

The latest suicide was reported in Hamirpur district of Uttar Pradesh on August 27. Parth Singh, 13, was found hanging in his bedroom, with his father’s phone in his hand. Reportedly, the game was open on the phone, which the police have seized for forensic examination.

The Blue Whale first made waves on July 29, when Manpreet Sahani, 14, jumped to his death from the roof of a seven-storey building in Andheri East, Mumbai. He had photographed himself sitting on the parapet just before jumping and had captioned it: “Soon, the only thing you would be left with is a picture of me.” The death was, at the time, suspected to be the first Blue Whale Challenge suicide in India.

“He was a decent child; quiet and polite,” said Arjun, the gatekeeper of Empire Residency, the building where Manpreet lived. “He rarely played with the kids in the society.” The residents of the building, still in shock, were reluctant to speak about the death.

The first floor, where the Sahanis live, was eerily quiet. Jaspal Singh Sahani, Manpreet’s father, who works in the aviation industry, talked to us through a small opening in the door. “The police have seized his gadgets and we are waiting for the report,” he said, with tears in his eyes. “We want to tell the world that he was a gem of a kid, but we would not say anything until the investigation is over.”

Deputy Commissioner of Police Naveen Reddy, Zone X, said the boy had only a mobile phone. “He didn’t have an iPad or a laptop, and he was not going to any cyber cafe in the neighbourhood,” Reddy said. The police had not found any link to the challenge in the preliminary examination, but Reddy said the forensic report would bring more clarity. The police, however, do believe that Manpreet used to play several games on his mobile and PlayStation. Reddy, who spoke to his teachers and friends, said Manpreet was an “expert in games”, but added that he was a bright student and that the “games did not overshadow his life”.

However, he was a WhatsApp addict and had very few friends in real life, said Reddy. “Most kids these days have only virtual conversations and this was prominent in this case, too,” he said.

Apart from the deaths, there have been reports of teenagers being pulled back from suicide. In Indore, Madhya Pradesh, classmates persuaded a class seven student of Chameli Devi Public School not to jump from the school building. In Solapur, Maharashtra, the relatives of a 14-year-old called the police when he left home after allegedly playing the game. He was soon brought back home.

Hari Narayan Chari Mishra, deputy inspector general of police, Indore, told THE WEEK: “We have issued an advisory urging students not to click on dubious links. We are also keeping a close eye on cyber cafes to ensure they do not help children download suspicious links.”

Dr Ajit Kumar Singla, deputy commissioner of police, Delhi, said: “We are visiting educational institutions and telling students to be more conscious while using the internet.”

The government has directed Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Yahoo and other technology giants to remove all links to the challenge.

However, such a ban would not work, said cyber expert Ritesh Bhatia of Mumbai. “It is not possible to ban the game as we don’t know its source,” he said. “Besides, several versions of the game have come up. Anyone can pose as a curator and play with someone’s mind.”

Moreover, the laws are such that it takes months to get the details of a source, said cyber lawyer Vicky Shah of Mumbai. “We can curb the menace when the legal system improves, cops become more cooperative and law enforcement agencies change.”

What experts say

But, why do the youth, especially teenagers, play games like the Blue Whale? “Search for novelty, excitement and ways to kill boredom nudge youngsters to try such self-harming games,” said Dr Manoj Kumar Sharma, associate professor at National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bengaluru. “At an impressionable age, they get easily influenced by latest trends and are bogged down by peer pressure, which leads them to dangerous territory. Sometimes, they are simply driven by their desire to belong to a group.”

Depressed youngsters are more likely to get hooked, said Dr Amit Sen, director of Children First, a mental health institute in Delhi. “So, instead of policing content, we must eradicate the root cause of the problem—depression among youth because of isolation and lack of communication,” he said.

According to the World Health Organisation, more than five crore Indians had depression in 2015.

Dr Kersi Chavda, psychiatrist at Hinduja National Hospital and Hurkisondas Hospital in Mumbai, said a phenomenon like this would affect only those who were psychologically weak. “For such people to feel accepted by peers, they feel they have to do certain things to prove they are strong,” said. “[A person can take up the] Blue Whale [challenge] by invite only. It is playing on the psyche of such people and is pushing them to go to extremes. It is not that the game is the problem, it is the person doing it that has the issue.”

He said parents should keep a close eye on teenagers who were withdrawn or had suddenly become quiet. “If he seems to be in his own world, is bunking a lot of classes or is indulging in self harm, it becomes incumbent on us to address the issue,” he said. Even adults were at risk. “There is a thin line between 19 and 20, a teen and a young adult. It is imperative to make sure that we keep talking to kids about any negativity affecting them. Conversation is the key.”

Besides, parents can fight technology with technology. “Don’t allow your child to use the computer when alone, check his browsing history, use parental locks, instal software that lock certain sites from popping up, and use an app blocker,” said Ritesh Bhatia, the cyber expert. “Police officers, teachers, parents and children have to be cyber literate. Only then will we be able to fight the predators of the virtual world.”

However, Maya Menon, associate professor of psychology at the Government College for Women in Thiruvananthapuram, said, “The whole episode may make parents and teachers control freaks. This will only lead to more complications. What is most important is that the communication channel between parents and children must always be live.”

Though there is fear among parents, no suicide has yet been conclusively linked to the Blue Whale Challenge. Dr Jinesh P.S., a forensic medicine specialist at the Kottayam Medical College, Kerala, said the relatives blaming the challenge could be trying to cover up an uncomfortable truth. “Nobody wants society to know that their kids suffer from mental issues, even if it is something easily treatable like depression,” he said.

WITH RABI BANERJEE & PRIYANKA BHADANI